Unpacking the ‘big sister’ dynamic in South Asian cultures

How do these age-based hierarchies affect our friendships?

Tasneem Pocketwala and Editors

10 Jun 2021

Diyora Shadijanova

It came as a shock to me when I first learned that people in American movies call each other by their first names. I thought that prefixing names with a ‘Mister’ or ‘Miss’ was a sign of politeness and formality. I’m Indian, and in our communities (as in most South Asian communities), you’re supposed to refer to someone older than you as, depending on your mother tongue, bein/didi (sister in Gujarati and Hindi) or bhai/bhaiyya (brother in Gujarati and Hindi). This instantly brings them closer to you, instilling a connection and transforming the atmosphere of interaction between the two of you into something familial and comforting.

But this epithet also tends to establish an age-based hierarchy that can be difficult to grow out of, because you can never supersede age: they’re always going to be older than you. This hierarchy creates a dynamic that, unlike a friendship, primes you to look at the other person as already having it all figured out. It even has the potential to influence one’s life, as it has does mine.

Growing up, I’ve met several of these “older sisters” whose choices and personalities have made an impact. There was Z; a brilliant academic and a school leader who lived in my neighbourhood. I’d often visit her house and watch as she applied make-up and styled her hair to the latest trends. She showed me that excelling in academics did not preclude exploring womanhood through beauty and self-care.

“This epithet also tends to establish an age-based hierarchy that can be difficult to grow out of, because you can never supersede age”

Then there was R; a dedicated media student who exuded a silent belief in her own success. R’s steady self-assurance was entirely devoid of the flamboyance that I usually associated with knowing one’s place in the world. It normalised quiet ambition. And there was F, who I watched struggle with her faith through her clothes in college, until she finally embraced it, transcending from not wearing the hijab to wearing it full-time. It gave me courage to wear the veil full-time too.

But looking back, I wasn’t ever able to develop a real friendship with these women. Nor would I be able to now, given the chance. Having begun the relationship in acknowledgement of the age gap itself, I was stuck in this dynamic where I was unable to view myself on a level with them, as a peer instead of an elder. To me, they’re always going to have more life experience and go through important life stages before me. So I felt compelled to think of myself as comparatively knowing less, being less worldly-wise, and playing catch-up with all the mysterious experiences the older women had already undergone.

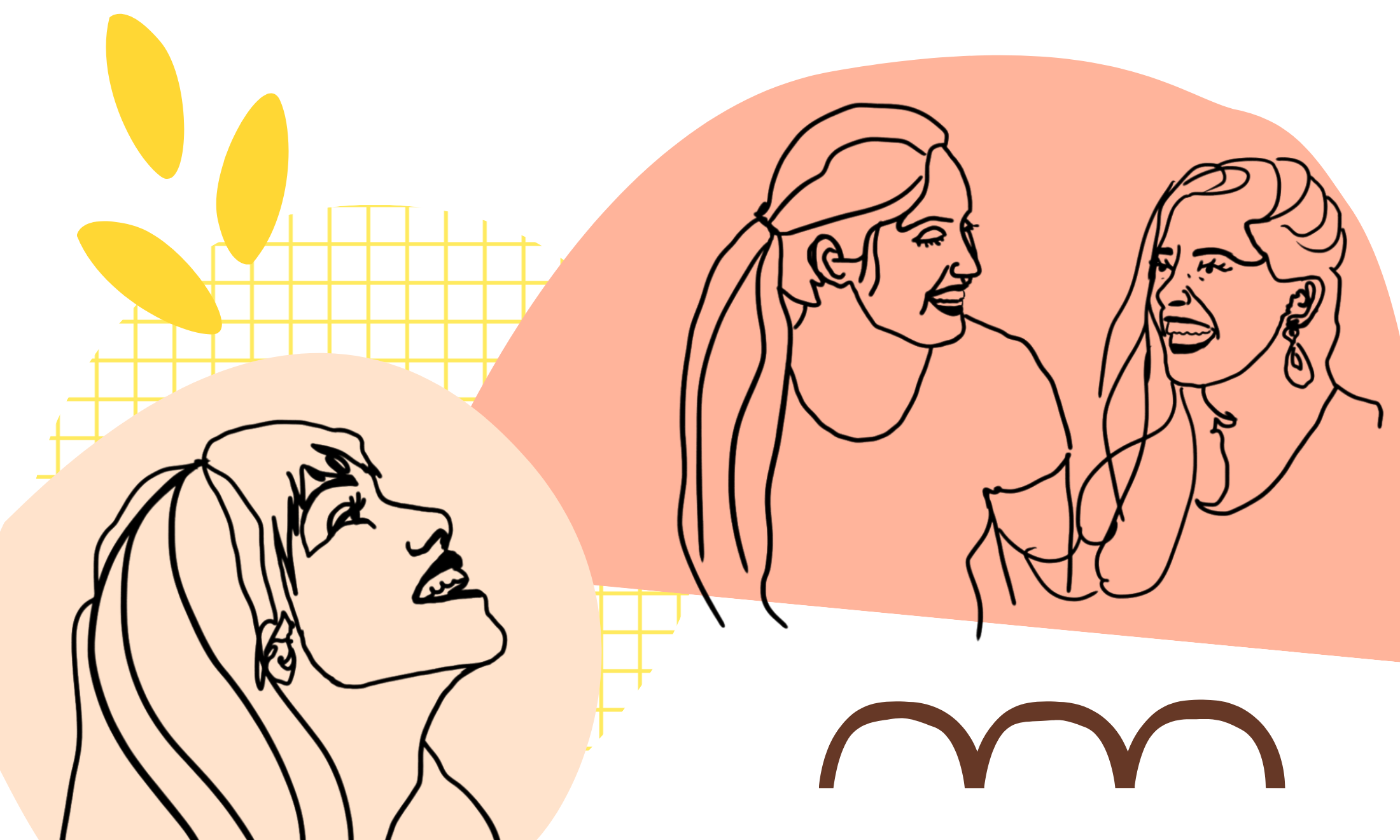

Were I not conscious of the conventional age-based hierarchy, I imagine I’d have something like a friendship with these women. I imagine there’d be an interchange of experiences and perspectives between us, a give-and-take of support. A collaboration of ideas, opinions and feelings based on the very difference of age and thus our world views, that would give us a wholesome understanding of life and where we were at in it.

“I felt compelled to think of myself as comparatively knowing less, being less worldly-wise, and playing catch-up”

My older sisters were always kind and friendly to me. But that friendliness itself created the distance, leading to our persistent unequal dynamic: when I called them “older sister”, it was a self-fulfilling prophecy. The system was set.

It’s not that friendships with an age gap are uncommon or unlikely. There can be benefits to such friendships. Older friends can be opinionated, smart, and much more sure about themselves, which can be infectious and buoy those of us who feel directionless. But there has to be the same level of interaction and reciprocity for these friendships to flourish, otherwise one is foisted upon a pedestal by the mere fact that they are older.

Respect for those older than you is embedded in language itself. In several Indian languages, like Hindi for instance, the pronoun you is translated into tu for those who are the same age as you or younger. For those older than you, the pronoun used is tum or, more politely and often formally, aap. When you’re talking to friends, you always use tu. But when it’s someone you’re calling “older sister”, you’re going to use tum – it follows the logic of the epithet bestowed. This reinforces the distance already established in age and assumed experience, precluding possibilities of a real friendship.

This isn’t a phenomenon limited to South Asian cultures though; the pattern is perceptible in the Western world too.

In Noah Baumbach’s film Mistress America, 18-year-old Tracy is a lost college student who meets the eccentric and assured 30-year-old Brooke, and is immediately captivated by her blithe and easy lifestyle. Brooke’s choices, personality, and the impulsiveness of her decisions would make you think twice about making a role model out of her, but through Tracy’s eyes, she is transformed into a “dazzling heroine”. Mistress America shows “the power dynamic that comes from having one idolise the other”.

“Over time I’ve realised that no one should feel inferior only because they’re younger”

In South Asian communities however, the didi suffix instantly creates a ready-made set piece of a relationship dynamic in which one is forever imparting wisdom, while the other forever receives it.

One of the most quoted lines from Mistress America, is when Tracy tells Brooke she feels inferior. “That’s stupid,” Brooke replies. “Don’t feel inferior.” Tracy, jolted out of her casual self-deprecation, instantly believes her. To her, it suddenly seems to be the most obvious thing in the world.

I realise that in many ways, I have let these older sisters influence me. Like Tracy, I looked at them as if they embodied the answers to my life’s questions. The specific gendered nature of this sort of dynamic can be traced to the fact that I didn’t really see too many women around me doing ‘radical’ things, like being ambitious or embracing both academia and personal care. So I latched on to those who seemed to represent these possibilities for me, even if unconsciously, certainly inadvertently.

Over time I’ve realised that no one should feel inferior only because they’re younger! For my part, I’ve learned to navigate the tricky waters of these lopsided relationships by either switching into English, a language that seems to have eschewed such gradations, or just calling everyone tum.