When will fashion brands stop sexualising the cheongsam?

Maison Cléo is the latest clothing company to appropriate the traditional Chinese dress. It should be the last.

Suyin Haynes

02 Dec 2022

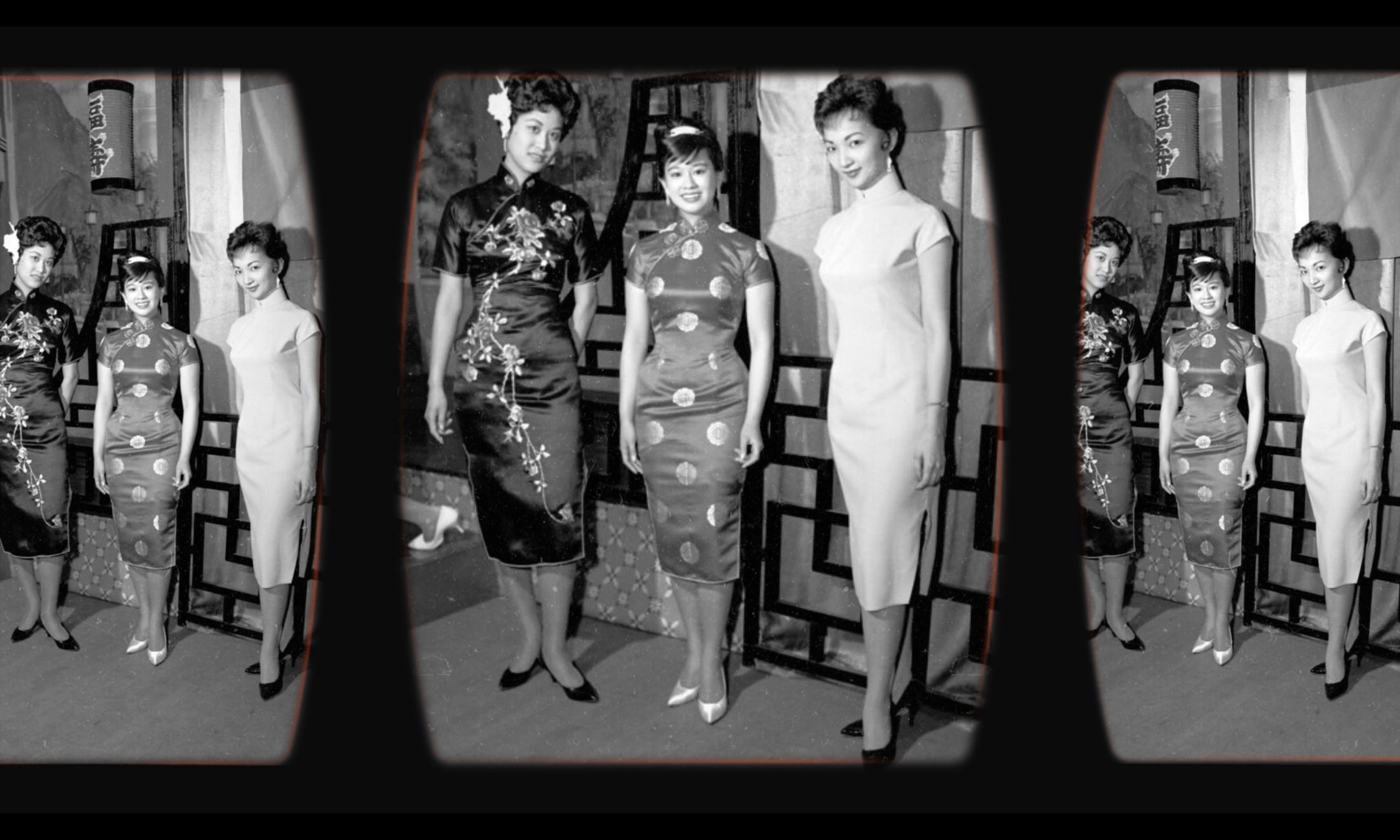

Province Newspaper, 1960 — Vancouver Public Library via Flickr

The caption on the Instagram post was joyful and emoji-laden: “❤️🔥💃🏻 New HOLIDAYS capsule launching this Wednesday!! ✨✨🏹 Delivered for Xmas time if ordered before December 4! 💃🏻💃🏻💃🏻🖤🖤🖤 be readyyyyy! ❤️🏹💘”.

And then a strange addition to French fashion brand Maison Cléo’s announcement about their holiday collection appeared. “turned off the comments as comments became racist […] Discussion = ok / insults = no. Thank you ❤️”.

The post shows a model wearing an interpretation (if you can call it that) of a cheongsam, or qipao, a traditional Chinese dress that is usually mid-length, made of silk, has side slits and is tailored to fit the body. Maison Cléo’s version however, looks rather different: it’s a minidress cut so short that it nearly exposes the model’s bum. The item’s description on the website shares that it was made with “amazingly beautiful real Chinese silk that I found from coming there”. There’s also a black velvet version designed in the same cut.

As a video by Racism Unmasked Edinburgh founder Feiya Hu notes, it’s by no means the first time that a fashion brand has appropriated the design of the traditional dress. A quick Google search will yield hundreds of results of various versions, ranging from high-end to high street. In 2019, Reformation received backlash for their leopard-print minidress, as did Little Mix’s collection with Pretty Little Thing, which saw the group pose on fairground rides wearing cheapened outfits that looked neither comfortable nor cool.

Now, I’m not excusing Pretty Little Thing and their moral bankruptcy here. But I find the Maison Cléo example particularly egregious. The brand, heralded as an influencer-loved slow fashion label, is handmade to order, and espouses the twin mantras of #NoChangeNoFuture and #FuckFastFashion – rallying cries to shop slowly, sustainably and ethically. The brand’s about page details their passion for “refreshing transparency” and “handmade clothing and authenticity […] that doesn’t follow any fashion calendar nor trend”.

However, it seems these ethics don’t apply when it comes to disrespectfully appropriating Chinese culture, nor any accountability or willingness to listen to feedback. After receiving dozens of comments on Instagram that critiqued the dress, alongside some highlighting the decision to cast a model who does not appear to be Chinese or East Asian in the campaign, the brand turned off comments on the post and inserted the addition to the caption – curiously calling the backlash and good faith efforts to educate the label on why the dress was problematic “racist”. Some users said that their previous comments appeared to have been deleted.

“It seems these ethics don’t apply when it comes to ripping off Chinese culture”

In comments on other posts criticising the dress, the person responding to comments on the brand’s behalf said that they felt “lost and sad”, and that “while others want to fetishist [sic] this type of dress (something I wasn’t aware of and i severely punish these actions), why can’t we understand that it’s not everyone’s motivation? Because it’s certainly not mine at all.”

It’s a classic response of fragility to any accusations of racism or appropriation; to turn to cries of “but this was not my intention! This has made me very sad! So much work went into this!”. And while this all may be true, ultimately it doesn’t stop the sexualised garment nor its impact from being racist or just plain ignorant. Maison Cléo clearly takes great pride in having sourced the silk material from China, as noted on the website and in comments, and the brand would have done well to learn more about the history behind the cheongsam/qipao; or better still, employ a Chinese designer to create the garment, which it appears was not the case. (gal-dem reached out to Maison Cléo’s press office for comment but did not receive a response).

Even the marketing of the dress isn’t immune from sexualised undertones in its photography. Interiors of a dimly lit bar, luxe floral wallpaper, burgundy and leopard print velvet furnishings; all conveying glamour and mystique with the red dress front and centre. The images may seem innocent at face value, but when coupled with the fact that the brand has erased any trace of authenticity or connection to the traditional dress, bar the literal fabric the garment was made from, it feels like a bad, Orientalist attempt at recreating a film set by Wong Kar-wai, the great master of Hong Kong cinema.

The cheongsam/qipao became popular in 1920s Shanghai alongside growing forces of globalisation and feminism, but its origins date as far back as the 17th century, inspired by garments worn in the Qing dynasty. As Quinxuan Han notes, its 20th century iteration marks “one of the earliest examples of the modern expression of individuality through fashion in China”; its growth was reflective of the transformation of modern society under the Republic of China, with implications and impacts across the region.

The rich history and context of the dress is not hard to find: there’s a wealth of fascinating information available, whether that’s looking at its significance and reimagining in recent decades, its relationship with the male gaze, or digital archives like cheongsam connect and Asian Fashion Archive. Nowadays, the cheongsam/qipao tends to be worn on special occasions, including weddings and dinners, and is often an item of clothing that people of East and South East Asian (ESEA) heritage wear at festivities that celebrate their family and heritage.

“That history and cultural context is something to be celebrated and appreciated, not sexualised and commodified for the sake of influencer approval”

That history and cultural context is something to be celebrated and appreciated, not sexualised and commodified for the sake of influencer approval. Although it certainly should be, this is not the last time that a fashion designer, whether that’s fast fashion or a brand that touts its apparently ethical credentials, will appropriate the cheongsam/qipao. The brand’s defence of the dress only reveals the apparent ignorance of how this type of fetishisation might actually connect to the lives of ESEA people and their lived experiences.

While it’s all too easy to market knock off versions of Chinese culture as ‘sexy party outfits perfect for the holiday season’, the bodies of ESEA women are objectified, fetishised, and in cases like the Atlanta spa shootings, are the site of violent attacks. Perpetuating these stereotypes produces real pain, and has real consequences — ones that can’t easily be managed by simply turning off comments and silencing discussion. Chinese culture is not your costume.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Boohoo’s attempts to appear ethical are empty and damaging – we must keep calling them out

This Lunar New Year, Asian communities deserve the right to grieve and fear

How the politics of representation mask fashion’s unethical underbelly