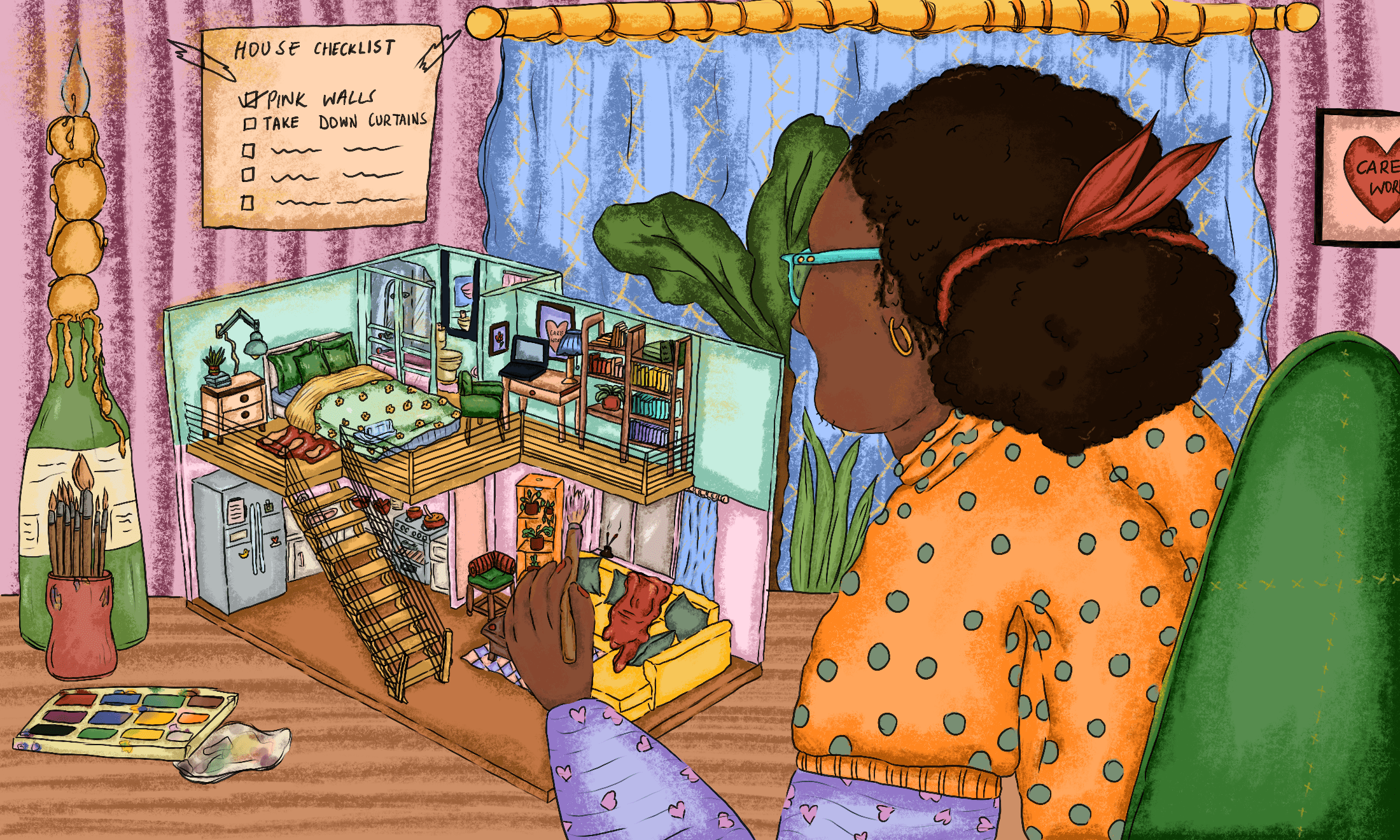

Illustration by Maia Magoga

I tend to tell new people that I’m diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome fairly quickly. I see it as pragmatic. They get a slightly better idea of how my brain works, they can help me with things that I find more difficult, and they understand why Leicester Square’s crowds are my personal seventh circle of hell.

Since moving to university, I’ve had to explain autistic spectrum disorder (ASD, formerly two separate categories consisting of “Asperger’s syndrome” and “autism”) to nearly every friend I’ve made. It makes sense; public exposure to neurodivergence, let alone ASD specifically, is sparse. Though representation is rising with shows like Atypical and Young Sheldon, autistic characters are usually men, and almost invariably white. ASD has a plethora of variables, and factors like gender and race can vastly impact the experiences of autistic people. Yet, in television and movies, only these specific presentations and circumstances are illustrated.

Most children with ASD are distinctly aware that they are different from their peers, and I was no exception. With literally no exposure to people like me, I grew up thinking that I was, neurologically, entirely alone. Even when exposed to autistic characters before I learned about my diagnosis in adolescence, it didn’t click that they resembled me; they were all (considerably older) men. Only their mindsets, abilities, and interactions with their surroundings were being portrayed. And as these were the only public, accessible depictions of ASD, I often caught myself analysing my behaviour and comparing it to theirs. I frequently questioned the legitimacy of my autism’s manifestation as a result of these differences.

“Autistic characters are usually men, and almost invariably white. But factors like gender and race can vastly impact the experiences of autistic people”

Autistic experiences vary by gender, too. Social interaction amongst girls, for instance, is significantly more dependent on subtlety and nonverbal communication than it is amongst boys. As it happens, autistic people find these things damn near impossible. Social expectations are also generally far higher for girls. Consequently, I found it much harder to make friends with other women and successfully interpret their exasperation. This is immensely common amongst autistic girls, but with no portrayal of this in mainstream media, I was isolated, and came to the conclusion that I was simply socially defective.

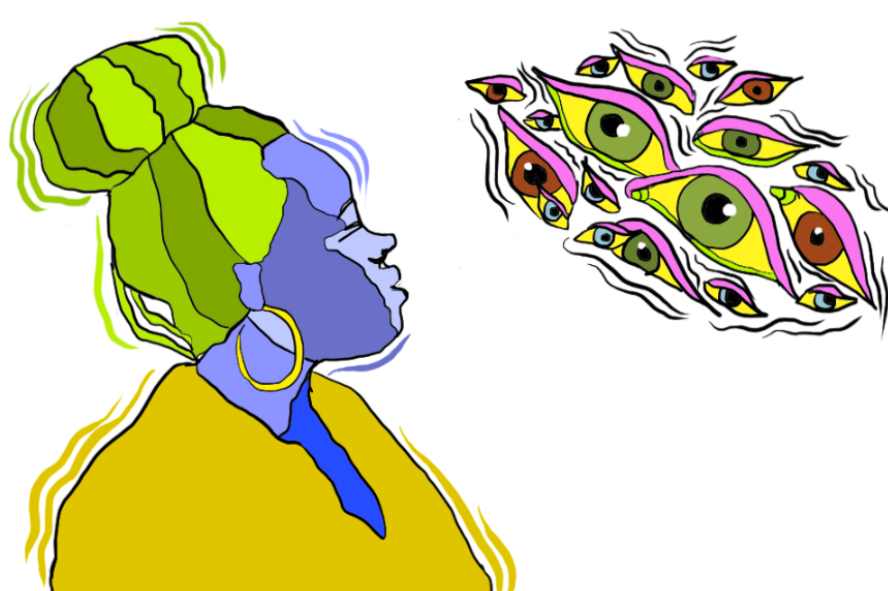

This isolation is amplified for autistic people of colour as they further diverge from their white, neurotypical peers. They often find themselves sacrificing part of their culture. I, for instance, didn’t speak for years; the health visitor suggested that being raised in Urdu alongside English was slowing me down, and resultantly, I never learned it. Furthermore, understanding of neurodivergence varies vastly across cultures, often generating significant obstacles to those trying to learn about ASD and seeking diagnosis. Autistic people of colour also face conscious and subconscious racism, which means that these differences are more likely to be viewed negatively. A white person who struggles socially is typically deemed “shy” or “withdrawn,” while I’ve repeatedly seen people of colour with exactly the same traits branded as “disagreeable” or “rude”. Autistic difficulty in deciphering unspoken dialogues, like racist microaggressions, makes it significantly harder for them to discern how much of the animosity they face is discriminatory.

ASD representation is already limited, and the few examples we have only showcase a very specific group of autistic people. Considering how multifaceted ASD is, the fact that nearly all autistic people featured in TV and movies are white men is perplexing. Networks and writers continually place them at the forefront of most narratives about autism, and these characters rarely deviate from the status quo.

“It is much tougher for neurotypical people to recognise autistic women and people of colour when they only associate autism with white men”

It’s true that men are more commonly diagnosed with ASD – but higher social pressure amongst girls and a diagnostic system created around boys and men are believed to influence these stats.

It’s invaluable for people on the spectrum to see characters who look and function like them. Greater representation of autistic people of colour would provide familiarity and reinforcement for the people who need it most. Words can’t express my sense of community and comfort when I learned that other people think and operate as I do. Seeing your most unorthodox traits — such as stimming, or anxiety surrounding nonverbal communication — showcased in a character and watching them work through the same specific issues is indomitably reassuring, particularly to younger people. A more diverse portrayal of ASD would bring crucial representation to people with complex, marginalised identities who could truly benefit from it.

Additionally, and crucially, if much of society has no experience with people like you, they can’t engage with the issues you face — they have no idea what they are. When people are aware of my ASD, they can understand and support me far more efficiently. It is much tougher for neurotypical people to recognise autistic women and people of colour (and for these autistic people recognise it within themselves) when they only associate autism with white men. Singular representations make general understanding of ASD flimsy and homogenous.

Television and movies are ideal vessels to illustrate these topics. The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air’s episode about racial profiling and Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s episode on sexual harassment depict these matters in a coherent, easily consumable format. While empowering those who are represented, the issues are accessible to those who are unfamiliar with them. This stimulates discussions about them and generates public understanding, allowing them to be tackled more effectively.

When autistic people are presented as a monolith, society views them as such. In the public consciousness, ASD becomes exclusively associated with Sheldon Cooper-esque men, while autistic women and people of colour lack equal recognition. It denies us reassurance, compassion, and even fundamentals like access to the diagnoses that we deserve. More diverse and nuanced autistic representation in entertainment would make accessing this so, so much easier.