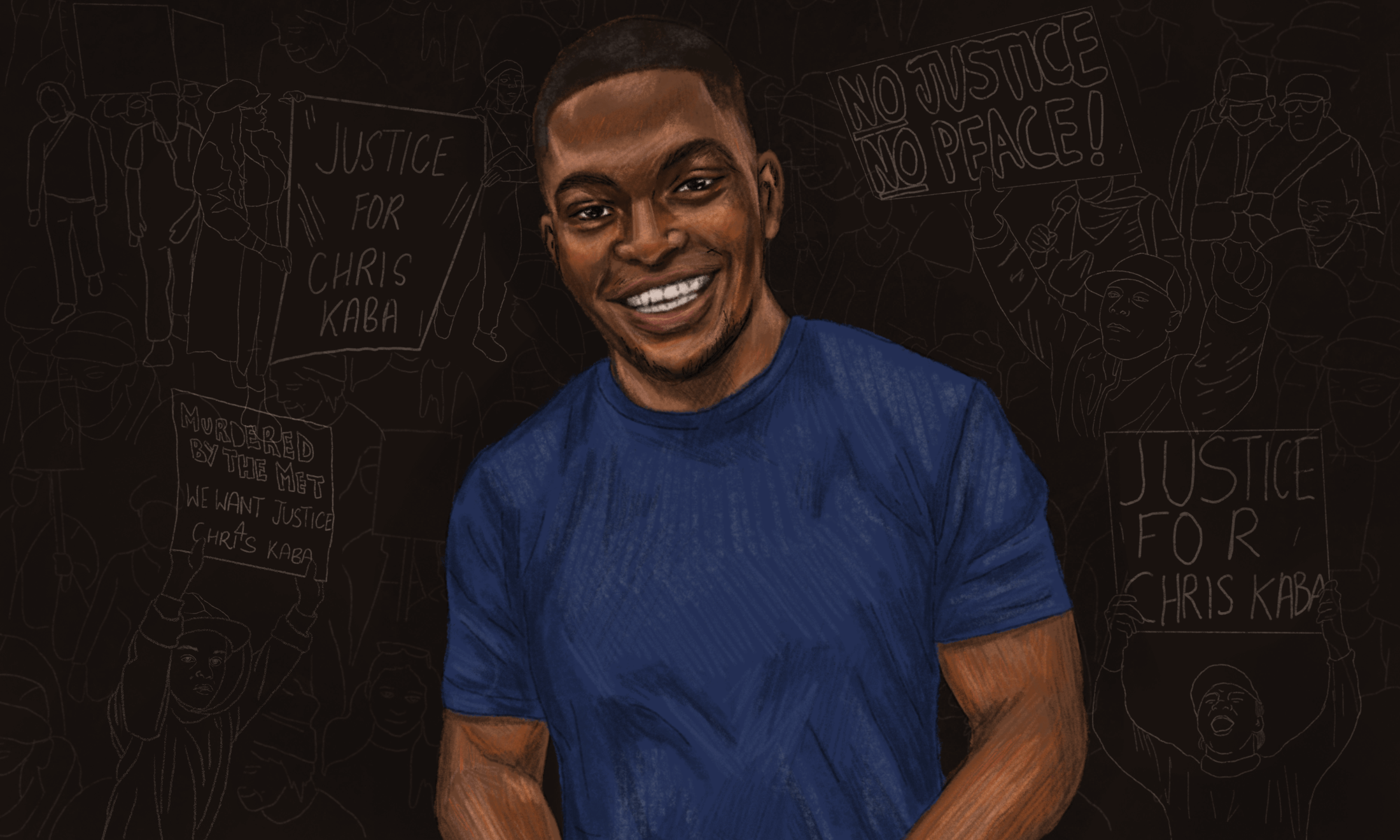

Illustration by Sage Anifowoshe @peachmuseumart

What does Black Lives Matter look like in Scotland, Ireland and Wales?

After the deaths of Sheku Bayoh, George Nkencho and Mohamud Mohammed Hassan, it's not just England having a racial reckoning.

Tomiwa Folorunso

03 Jun 2021

Content warning: racism, descriptions of death, police brutality

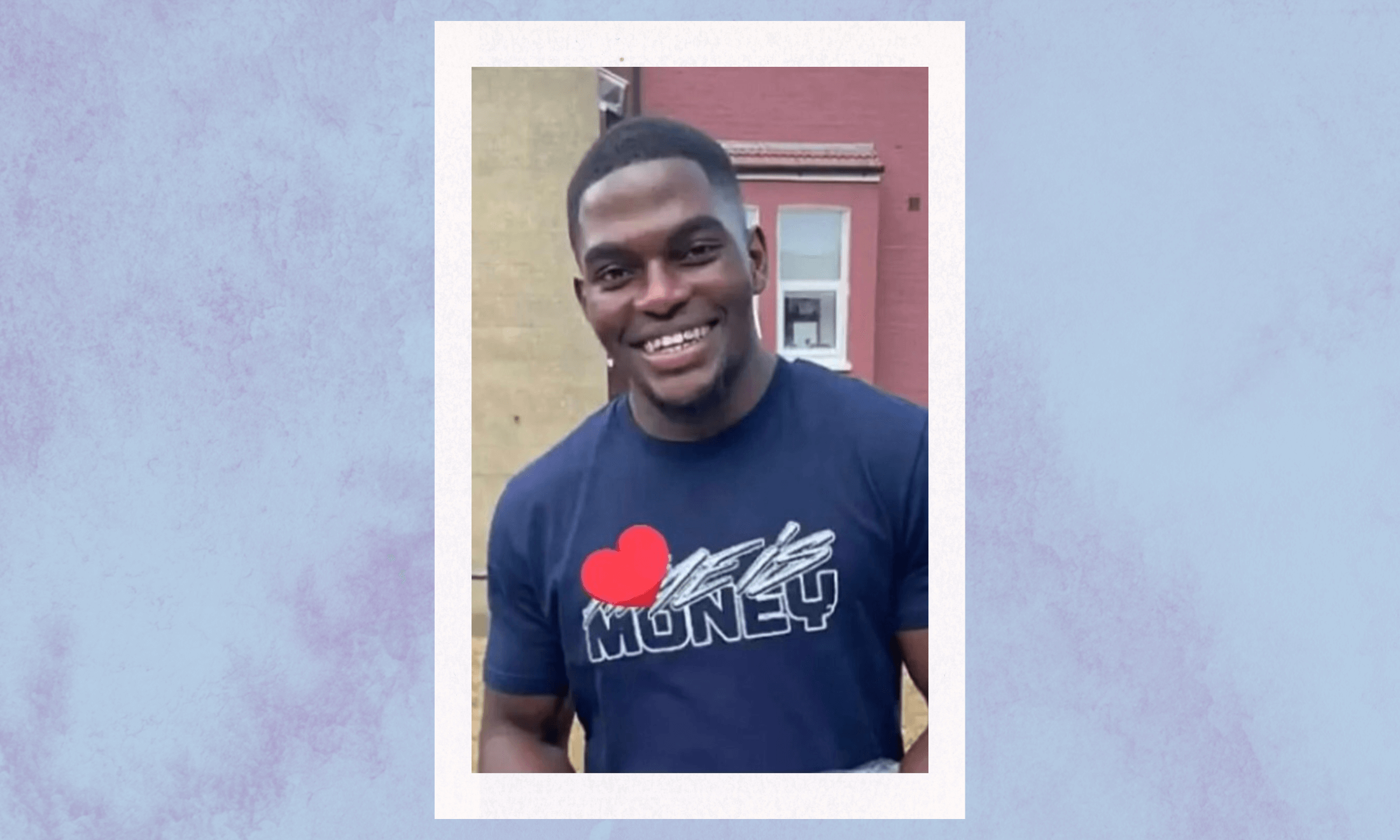

Early on a Sunday morning in early May 2015, Sheku Bayoh was confronted by police on the street outside of his Kirkcaldy home. He was restrained and later pronounced dead in hospital. In December 2020, outside of his family home in Clonee, Ireland, George Nkencho was shot five times during a standoff with armed Gardaí. He later died in hospital. In January 2021 Mohamud Mohammed Hassan was arrested in his home in Cardiff, Wales, released without charge the next day. His family alleges he was assaulted in custody and died of those injuries the next night.

Almost exactly five years after Sheku Bayoh’s death, and 3,737 miles away from Kirkcaldy, in Minneapolis, America, George Floyd was murdered by a police officer. During the summer that followed, Black Lives Matter solidarity protests took place across the world, including in Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

The deaths of Sheku, George and Mohamud in police custody should have shaken their respective nations in the same way the death of George Floyd did from across the Atlantic Ocean. But many activists and organisers don’t think they did.

Scotland, Ireland and Wales have smaller population sizes than the US – their combined total barely amasses that of England. Each country has a strong nationalist sentiment and has historically viewed itself as separate from the United Kingdom. Ireland has been independent since 1922, while Scotland and Wales both have devolved governments, and in 2016 a closely-fought independence referendum took place in Scotland.

All three nations have what is perhaps most commonly described as an ‘inferiority complex’. They often position themselves on moral high ground to preserve their journey to independence. They also seem to be united in finding it more comfortable to empathise with black people and have vital conversations about institutionalised racism when it’s in an American context.

New Interest

After George Floyd’s death, Irish communities began questioning what the Black Lives Matter movement meant in an Irish context, but months later, when George Nkencho died, there was silence.

“It was only the Black community and a handful of white people that were talking about George Nkencho and explaining how you can’t say Black Lives Matter only in America, and when a Black man dies on your own shores, you’re just silent,” says Sandrine Ndhao, co-founder of the Irish anti-racist grassroots group, Limerick Movement Against Racism (LMAR).

For Black and other ethnic minority activists and organisers in these nations, navigating these white, often hostile spaces, to support marginalised communities is a challenge. But, despite everything, the Black Lives Matter protest movement of 2020 has brought their communities closer together, and new networks and organisations have formed, with community and anti-racism at their heart.

“In America, it took five days [to arrest and charge Derek Chauvin, the officer who knelt on George Floyd’s neck], in Scotland, it’s taken five years and we’re still waiting,” says Kadi Johnson, Sheku Bayoh’s sister. She has worked tirelessly to keep her brother’s name alive – even as the handling of the case continues to expose the racism within the Scottish justice system.

Kadi recounts that to her it felt as though the noise surrounding Sheku had faded away – but the similarities between the events surrounding his death and George Floyd’s sparked everything up again. “Especially for the young ones who have grown up in the past five years, they’re more aware and they are more alert. They want to do more. They want their voices to be heard. They are the ones who are really driving the movement now,” she adds.

“It was only the Black community and a handful of white people that were talking about George Nkencho and explaining how you can’t say Black Lives Matter only in America”

Other people in the community still can’t believe this happened in Scotland or fathom that Sheku’s death had anything to do with race, she says. But all Kadi and the rest of their family want is for their brother not to have died in vain; for lessons to be learnt and for no other family to suffer how they have. They want to be able to breathe properly again.

In a similar way to how Kadi and her family have been organising with the wider community, in the 1980s Black people and other people of colour would organise in more Pan-African reflects Laura Bilton, one of the founding members of the present incarnation of the BLM Scotland chapter. It was re-launched by a network of activists across Scotland in 2020. Based in Edinburgh, Laura has worked in the anti-racism space for 10 years.

Speaking about how anti-racist activism has developed in the country since the 1980s, she explains that she would often see white people who were interested in the work but wanted to “control the narrative”. This caused a lot of the work to be ineffective from a policy standpoint, with what she perceived to be too much of a focus on research rather than action.

“The Scottish government ultimately left communities [of colour] to organise and make changes themselves,” she says.

In contrast, over the past few months, BLM Scotland has been working slowly but intentionally, to create the network and structures to support Black populations across Scotland. They acknowledge that the Black population in the country is “really, really small” and mainly concentrated in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

“We don’t really have areas that are ‘Black areas’ in Scotland. So, it’s a bit different, it’s a community that’s held together in different ways,” says Laura.

But as this community becomes more visible and present, so do white nationalist counter-protesters. In June 2020 they turned up at a peaceful protest at the Melville Memorial (a commemoration to Henry Dundas, a 19th-century politician whose actions lead to a delay in the abolition of the slave trade) in Edinburgh’s bustling St Andrews Square, under the guise of protecting the statues and their perceived birthright. Their presence showed the frightening side-effects of nationalism and the static portrayal of who a Scottish person can be. In short: it’s not all red hair, pale skin and kilts.

Realities of racism

Similarly, in Wales, little space is given to the idea that a person could be both Black and Welsh. In July 2020 BLM Cardiff and Vale, alongside Stand Up To Racism Cardiff, protested against the naming of a development ‘Ffordd Penrhyn’, which is the Welsh word for ‘peninsular’, but also seemed to be a reference to Richard Pennant, who profited off the enslaving of people in Jamaica.

“A lot of Welsh nationalists came and attacked BLM Cardiff and Vale and Stand Up To Racism Cardiff because they felt as if we were being ignorant to the Welsh language and ignorant to Welsh history,” says Sabrina Thakurdas, one of the founding members of the third incarnation of BLM Cardiff and Vale, that began last summer. What ensued was the tiresome rhetoric of “you’re not from Wales because you’re Black or brown”, she adds.

It begs the question as to whether the issue with these nations is not the inability to understand what racism is, but that they could be the perpetrators of it. “Welsh people think they aren’t racist because of the rivalry between the English and the Welsh. They think racism stops at being Welsh, not being Black and, Welsh,” says Sabrina.

“Over the past few months, BLM Scotland has been working slowly but intentionally, to create the network and structures to support Black populations across Scotland”

Within preconceived feminist or liberal spaces, this ignorance towards race continues, and the identities of those for who the spaces are created are overlooked and purposely ignored. In Ireland, a self-organised and non-hierarchical group, Migrants and Ethnic Minorities for Reproductive Justice (MERJ) was founded in 2017 by migrant women of colour in Ireland who were frustrated that they were not being seen despite being actively involved in the campaign for abortion rights.

Oduenyi*, one of the group’s members, says that attempts to explain to neo-liberal feminist groups why their comments, or work, is not intersectional and hurts ethnic minority and LGBTQI+ communities, are either met with silence – or they’re branded ‘radical feminists’. The lack of recognition seen within the feminist space is a reflection of Ireland in more general terms and its handling of racism.

Similarly to Scotland and Wales, the colonial past of the country has produced a strong Irish identity, grounded in a white supremacy. This means the racism suffered by Black and brown people cannot be addressed because, in the eyes of the nation, in comparison to England and America, they’re just ‘not that bad’.

Oduenyi believes they “cannot fix the problem unless [they] really evaluate and just say openly, ‘hey, we’re not inclusive but since we can recognise this, we can do better”.

According to Sabrina, the death of Mohamud Mohammed Hassan has also brought these ideas to the forefront in Wales, both inside and outside of these spaces – with the discourse around the case being delegitimised by those arguing that the 24-year-old was “involved in illegal activity”, Sabrina says. “They’re just looking for a reason to understand what happened and not realising this person is an actual innocent man who didn’t deserve to die by the state. It’s like it’s validation that people need.”

Alternative justice

While some white people struggle to see Black people as victims and are wedded to carceral forms of justice, for many activists the concept of abolition is not new. In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter resurgence, communities of colour are having this conversation more and more, considering and imagining what justice can look like in their nations.

“[Mohamud’s death] has sparked a lot of conversation within these communities because no one should die at the hands of police,” says Shash Appan, an activist who is a member of Glitter Cymru – a Cardiff based social meet-up for LGBTQ+ Black and POC people. “I like to think that I’m seeing more people that are very wary about the police coming out to a mental health crisis. And asking why aren’t they releasing the CCTV footage?”

Similarly to the situation in Scotland, where those holding the power in political and institutional structures talk but affect little radical systemic action, Welsh anti-racist organisations are aware they should not put all their eggs into a metaphorical institutional basket.

Shash and the people she works alongside understand and operate with the knowledge that any engagement with those in the system is “just lip service” to try and appease the community. “We know they are not allies of marginalised communities,” she adds, acknowledging that it’s imperative not to rely on institutions to change. Instead, she puts energy into getting allies behind the movement and finding alternatives to the criminal justice system that don’t rely on punitive measures and incarceration.

“Welsh people think they aren’t racist because of the rivalry between the English and the Welsh. They think racism stops at being Welsh, not being Black and, Welsh”

Finding alternatives to state justice is also a focus of MERJ’s current work. Since the death of George Nkencho there’s been a renewed desire to take a holistic and anti-neoliberal approach to justice – the group is creating a series of workshops on non-carceral feminism.

“When you even talk about Black Lives Matter, it’s really important that people don’t feel forced to go to the police or the state for protection. The aim of the workshops is to have people trained to be able to enact community accountability or also to be able to reduce interpersonal violence,” says Oduenyi.

Independence movements

Independence does not fix a country’s problems, but it could provide an opportunity to create a new country that is unafraid to interrogate itself and its values. Especially, in Wales and Scotland, where an independence referendum is on the political agenda, it’s imperative that the work of Black and POC communities is engaged with.

In Wales, the number of people opposing Welsh independence is decreasing. At their special conference on independence in February, Plaid Cymru promised they would hold a referendum on independence in their first term if they won a majority. In May, Labour remained in power and the party has said they do not support, nor will be calling for a referendum. But, the establishment of groups like POC 4 Welsh Independence and YesCymru show that independence is on the political agenda. Shash describes independence in Wales as a movement they are working towards that is perhaps not as established as in Scotland.

In the 2014 Scotland Independence referendum, the ‘no’ side won 55.3% to 44.7%. Post-Brexit, another Conservative government and the Scottish Nationalist Party remaining as the largest party in the Scottish Parliament, it is almost certain that another referendum will take place during their next term, and it could very likely be a ‘yes’ vote. But as Laura reflects, the country has to carefully walk the fine line – if there is one – between patriotism and racism. “ [An independent Scotland] is about making space for everybody.”

Even in an independent Ireland, there is still not the necessary interrogation into the country’s racism. “With our history, we were ‘slaves’”, Oduenyi explains. “We were considered to be slaves with the slogan, ‘no blacks, no Irish, no dogs’.” The momentum of the 20th-century racist slogan hogs healthy discussion about how to address racism in an Irish context. And it was during Summer 2020 that for the first time the country started to talk about the racism against Black people that had existed for decades.

Legacies

The deaths of Sheku Bayoh, George Nkencho and Mohamud Mohammed Hassan have shaken their Black communities. For many of us, their deaths have been the most violent evidence of racism seen in our lifetime, in such close proximity. From my mum’s home in Edinburgh, I can walk five minutes to the coast and see across the water to Kirkcaldy where Sheku lost his life. His death, George and Mohamud’s deaths, are a stark and sad reminder that even if we call these nation’s home, thinking of them as places where we should be safe and protected. They are not.

While white allyship has been short-lived, in the aftermath of the men’s deaths, grieving communities have come together. Organisations, activists and individuals committed to re-thinking justice outside of state and societal boundaries. Justice with community and care centred are paving the way not necessarily for independent nations, but certainly for anti-racist ones. The POC populations in Scotland, Ireland and Wales might be small – but they’re undoubtedly mighty.

In May, in the Southside of Glasgow residents came out of their homes to peacefully protest against the UK Immigration Enforcement that attempted to remove two men from their homes. Solidarity did not just come from the rest of the city, or Scotland but England, Wales and Ireland too. It was a beautiful moment that proved even though we are all navigating our own political climates, in the face of oppression, and racism we are stronger together.

As Sabrina says, “A poor Black or brown person from Wales faces the same issues as a rich Black or brown person from England, the state is still the oppressor. It’s people in power oppressing those below them, that’s what we should be fighting against, together.”

*Name has been changed to protect identity

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?