Canva

Why Indigenous land rights are key for saving the planet

Biodiversity conservation has a dark colonial history, but now is the time to get things right.

Joycelyn Longdon

17 Feb 2022

Welcome to gal-dem’s monthly ‘It’s Happening Now’ climate column, exploring the intersections of race, class and marginalisation within climate breakdown. As current climate conversations overwhelmingly lack both heart and accessibility, Joycelyn Longdon, an environmental PhD student at Cambridge, tackles the subject from an education and action-focused perspective – not for aimless doomism.

When it comes to the climate crisis, questions about carbon seem to dominate everything. But there is more to this crisis than carbon. At the same time as experiencing climate change, we are also living amidst a biodiversity crisis.

My doctoral research at the University of Cambridge is embedded in developing community-designed, Indigenous-led technology to monitor biodiversity. As I prepare for my first field trip set for March 2022, speaking with conservationists on the ground in Ghana, the importance of biodiversity protection for the planet and people has grown ever clearer. The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis are essentially one and the same. Despite being extremely vulnerable to climate change, our ecosystems (and the biodiversity they hold) help the earth regulate its climate and so their protection becomes a key solution to the climate emergency. For example, the reversal of biodiversity loss could account for around 30% of the global action required to stabilise our climate.

“The biodiversity crisis and the climate crisis are essentially one and the same”

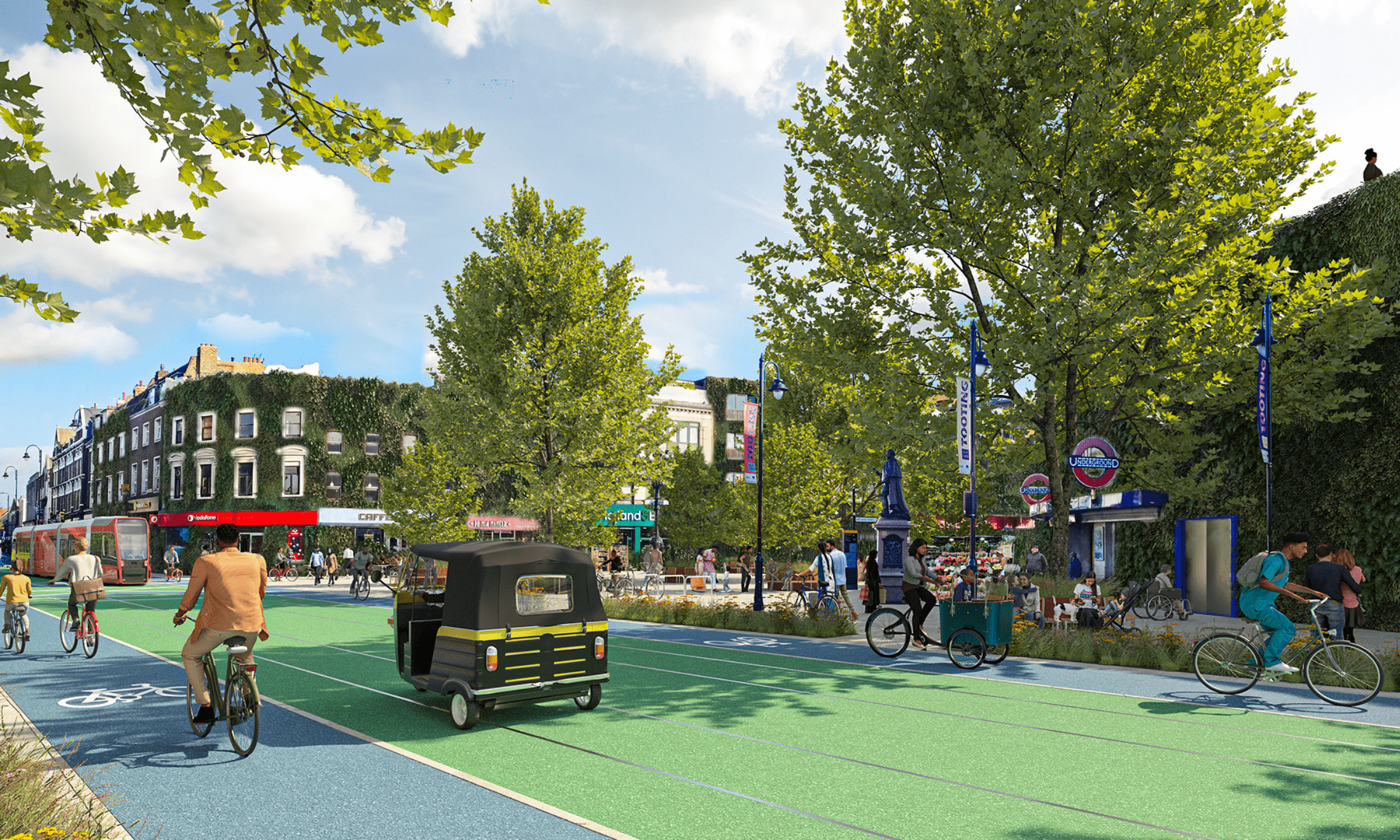

This revelation has catalysed the implementation of conservation initiatives around the world, from the efforts to Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) programme to the most recent 30×30 Initiative, which plans to protect 30% of the Earth by 2030 (through National Parks and Protected Areas). While these projects have noble motivations and goals, they tend to overlook a crucial perspective – that the foundation of biodiversity protection lies in Indigenous land rights.

Despite accounting for only 5% of the world’s population, Indigenous communities protect over 80% of the world’s biodiversity. The silencing of Indigenous peoples and Local communities (IPLCs) around the world, and the invalidation of their conservation techniques, has led to the unfortunate need for researchers to provide data and evidence for what these communities have long known; Indigenous peoples and Local communities provide the best long-term outcomes for conservation.

In 2021, the first major report by a UN agency recognised and documented in detail the efficacy of Indigenous conservation. The study found that 59.7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have been avoided thanks to Indigenous forest conservation in Bolivia, Brazil, and Colombia alone. That’s the equivalent of taking roughly 12.6 million vehicles out of circulation for one year. Two years earlier, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body of scientists who present regular scientific reports on our climate to inform policymakers, acknowledged for the first time that we must protect community land rights to save forests and fight climate change.

“Biodiversity conservation up until this point has had a dark colonial history”

Indigenous leaders from 42 countries responded by explaining how their “traditional knowledge and holistic view of nature enables [them] to feed the world, protect our forests, and maintain global biodiversity” but made clear that this only has a chance of working if there is “recognition of the customary rights of IPLCs to govern their lands”. Unfortunately, despite any progress that has been made in the recognition of IPLCs as key actors in the fight against climate change, not only have they been historically persecuted, threatened and severed from their lands, but they still face violence today.

Biodiversity conservation up until this point has had a dark colonial history that saw IPLCs treated not as humans but as flora and fauna (collections of plants and animals). Also, it’s estimated that up to 10 million people (and probably more) have been displaced from half of the World’s Protected Areas – all in the name of biodiversity conservation. Bernhard Grzimek, a German wildlife campaigner in East Africa, once said, “a national park must remain a primordial wilderness to be effective. No men, not even native ones, should live inside its borders”. It is dated and violent perspectives such as these that fuelled destructive actions of the past, and still persist today.

In Cameroon, for example, the Indigenous Baka from Banana and Bangoy villages “know the forest next to Boumba Bek/Nki National Park very well”. Their connection to the forest, as detailed in a report from the Forest Peoples Initiative, is based not only on their proximity to it, but more so on their belief that “the forest is [their] foster mother”. They follow a practice of “regeneration, being based upon respect for the rhythms of nature”. Boumba Bek/Nki National Park is in the process of formal classification as a National Park, which means it will be officially conserved by the state government. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is primarily managing this process, through dividing the park into zones. This will create borders across communities and restrict the Baka from living with the forest, enforced without their free, prior or informed consent. As a result, the community have effectively been marginalised from decisions on their own land and resources by one of the biggest conservation NGOs in the world.

“Luckily, there are many who have already dedicated years of their careers to firmly demand, and make tangible, Indigenous land rights”

But it is not just modern conservationists who threaten IPLCs today. Encouraged by the right-wing policies of Jair Bolsonaro, industrial oil and gas exploration, logging and mining has surged in Brazil, resulting in the destruction and degradation of the land of many Indigenous communities. Those who stand up to defend their environment risk their lives. In the 2020 Global Witness report, Brazil was found to be one of “the deadliest countries for environmental defenders”. With the new “Marco-temporal” law looking to be passed by Bolsonaro, which only acknowledges the rights to the land of Indigenous people who can prove their occupation of the said land in 1988, the number of killings is set to only increase.

At a time when we need to change everything about the way we live and operate, there stands a huge opportunity for countries, conservationists, activists and policymakers. Luckily, there are many who have already dedicated years of their careers to firmly demand, and make tangible, Indigenous land rights. These include organisations like the Forest People’s Programme (FPP), which work alongside Indigenous communities to advocate for land rights within forest landscapes, to the Global Alliance against REDD, a Project of the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN), advocating for their self-determination in land management and the reversal of destructive conservation policy.

Slowly, we are seeing this type of advocacy work produce positive results. Take Paraguay for example. After 23 years of fighting, the Sawhoyamaxa community of Enxet people in the remote Chaco region of Paraguay had 14,404 hectares of land returned; a German cattle ranching business was previously using the land.

Luckily, we don’t have to be scientists or activists to support land rights actions. We can read deeper into the topic, educate ourselves and increase awareness. More importantly, there needs to be an interrogation of conservation initiatives, especially those used to do carbon offsetting. Are our emissions worth the violence and persecution of the forest dwellers pushed out to make space for the forest plantation providing these “offsets”?

Instead, it’s worth learning from and supporting the following Indigenous land rights organisations:

- The Forest Peoples Programme

- The International Land Coalition (ILC)

- Land Rights Now

- The Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN)

- The Women’s Earth Alliance, Sacred Earth Advocacy Network

Safeguarding our natural world can’t ever be about severing the connection between humans and nature. It’s about finding the beautiful balance of mutually beneficial coexistence. More conservationists should not only look to IPLCs for this guidance, but also push to protect their rights.