Photography courtesy of Channel 4

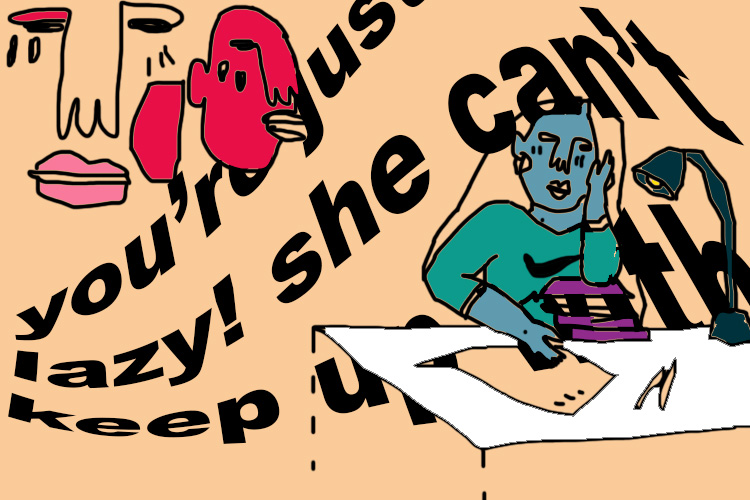

Conversations around black Britishness in the mainstream media has almost always been preached through the lens of whiteness. Our cultures are contorted into fickle narratives around youth violence and chicken-box haikus, served on a plate of anti-blackness and glugged down with a large glass of white gaze. With this longstanding history of disregard for cultural nuance, hand-in-hand with the fact that black communities often aren’t allowed to tell our own stories, it isn’t surprising that these conversations have evolved into a tennis match, batting back-and-forth between the fine line of “representation” and “respectability politics”. Dialogue around accurate and culturally-aware representation is important, but pushing respectability politics is not only detrimental to black communities, but also a complete waste of our time and energy.

You could argue this has been a great year for black creatives fortifying tangible and visible large-scale work – from the rebirth of the London drama Top Boy, to television’s favourite island sweetheart Ovie Soko, to projects like 56 Black Men, which took over billboards and bus stops with images of black men wearing hoodies in an attempt to combat “stereotypes” around black men. On the other hand, the criticisms around these topics have been rife, and rightly so. In all instances, I question why we are so eager to sensationalise individuals as examples of “The Good Black” rhetoric and point them out to white viewers like needy children begging for the attention of a negligent adult. A lot of what we call “representation” or “challenging stereotypes” fits neatly into the pocket of white gaze-watching, and at some point we must ask ourselves who we are attempting to appeal to, and why? When did we get so hellbent on upholding racist respectability politics as a form of dismantling systemic oppression?

“Misplaced energy is being directed towards critiquing other black makers, rather than critiquing the racist structures of the British media”

Recently, Black Twitter was set ablaze in a clash of ethics amidst the hype around the latest season of Top Boy, and I wasn’t surprised to see a split in dialogue when it came to the themes of the show. Demands for Top Boy to cease to exist in the tune of a tap-dancing jingle and comedian London Hughes was among the show’s loudest critics. After Ashley Walters clapped back at her, London penned a piece that called Top Boy a “step back” for black British culture. This was shortly followed by an interview in the Guardian about her latest ventures, where she claimed that there were no black British women who were household names barring Naomi Campbell.

London makes valid points regarding the cement ceiling of British media for black creatives, and the need to represent black Britishness in its entirety to add to the canon of black British entertainment – which includes joys such as Desmond’s, Three Non-Blondes, The Lenny Henry Show, Little Miss Jocelyn, Dubplate Drama, Chewing Gum and Luther (nevermind my mum’s personal favourite household name Trisha Goddard) to name a few. British media is not accommodating of new talent breaking through to the mainstream. Many black British creatives simply head for the USA, and most shows that do make it onto our screens in the UK last for just a few seasons before being cancelled. In this respect, London has every right to be wary of British media and its consistent anti-black treatment of black creatives in the UK, especially hypervisible black women. There is a legitimate threat of being boxed in that black people across all creative industries are constantly pushing back against.

“A black boy playing the piano in a train station and a black boy hanging around a street corner with his friends both deserve to be treated with the same level of decency and basic respect”

However, misplaced energy is being directed towards critiquing other black makers, rather than critiquing the racist structures of the British media – and this has left many people with a bad taste in their mouth. The latest Top Boy season explores boyhood, manhood, friendship, family dynamics, immigration and the reasons why people may turn to crime and violence in the first place – London’s article boils the show down to a guns-blazing, aimlessly violent drama about drugs and knives. She only confirms this in her later interview, stating: “Cool, have shows like that, but then also, have other shows. If you didn’t have any black friends, you lived in Brexit Britain and you looked on TV, you’d think we are all grime rappers.” Shows like Top Boy should be able to exist alongside other dynamic work looking at other aspects of black Britishness, but the crux of “Brexit Britain” racism isn’t due to Top Boy existing, and in actuality, we haven’t even had that many shows like Top Boy, so this clearly isn’t the real issue at hand.

London also isn’t the only person to take to mainstream media to talk about black visibility, and it’s tiresome to see a pattern of respectability politics being played out across mainstream media platforms that weren’t designed to serve black communities with dignity and cultural sensitivity. Earlier this year, journalist Will Njobvu hailed Ovie as “our national treasure proving young black men are not who you think we are”, stating his “quirky personality has turned the stereotype of the aggressive black male on its head”. Cephas Williams, founder of 56 Black Men also received backlash after tweeting a video of a young black boy playing Nuvole Bianche on a piano in a train station with the hashtag “#IAmNotMyStereotype”. These types of comments hold exceptionalism as the key to dismantling racism without asking ourselves who we might be affecting in the process. A black boy playing the piano in a train station and a black boy hanging around a street corner with his friends both deserve to be treated with the same level of decency and basic respect. And in light of mainstream media propaganda against black boys in particular, we could do with more well-rounded and in-depth examples of black boyhood and manhood that doesn’t place the responsibility on black communities to be exceptional or “beat” a racist stereotype.

“Ideas around ‘challenging stereotypes’ pander to the same white viewership that criminalises black communities, whilst simultaneously placing the onus on said communities to bend over backwards for our supper”

Often, ideas around “challenging stereotypes” pander to the same white viewership that criminalises black communities, whilst simultaneously placing the onus on said communities to bend over backwards for our supper instead of directly questioning the systemic structures that create these racist stereotypes in the first place. It all of a sudden becomes easy to “other” oneself – but we are multifaceted people, and this isn’t an either/or game. Whether intentional or not, the differentiating of young men caught up in youth violence to an influencer from Love Island, in the context of having something to “prove” is a play on respectability politics.

The desire to represent the multifaceted, non-monolithic faces of blackness cannot come from a place of attempting to appease whiteness, and the need for acceptance is symptomatic of the myth that there is a level of “black excellence” or “good immigrant” action that can overthrow the very purposes of white supremacist structures. In other words – racists gon’ racist, so you may as well do you to the fullest.

Respectability politics will never be our friend, and in fact encourages black communities to execute the work of white supremacy. I’m glad these conversations are being pushed to the forefront of our communities, but current conversations around this prove how far we have to go in the fight against white supremacist ideology.