These zine-making girls are battling expectations and refusing to be spoken for

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan

08 Mar 2019

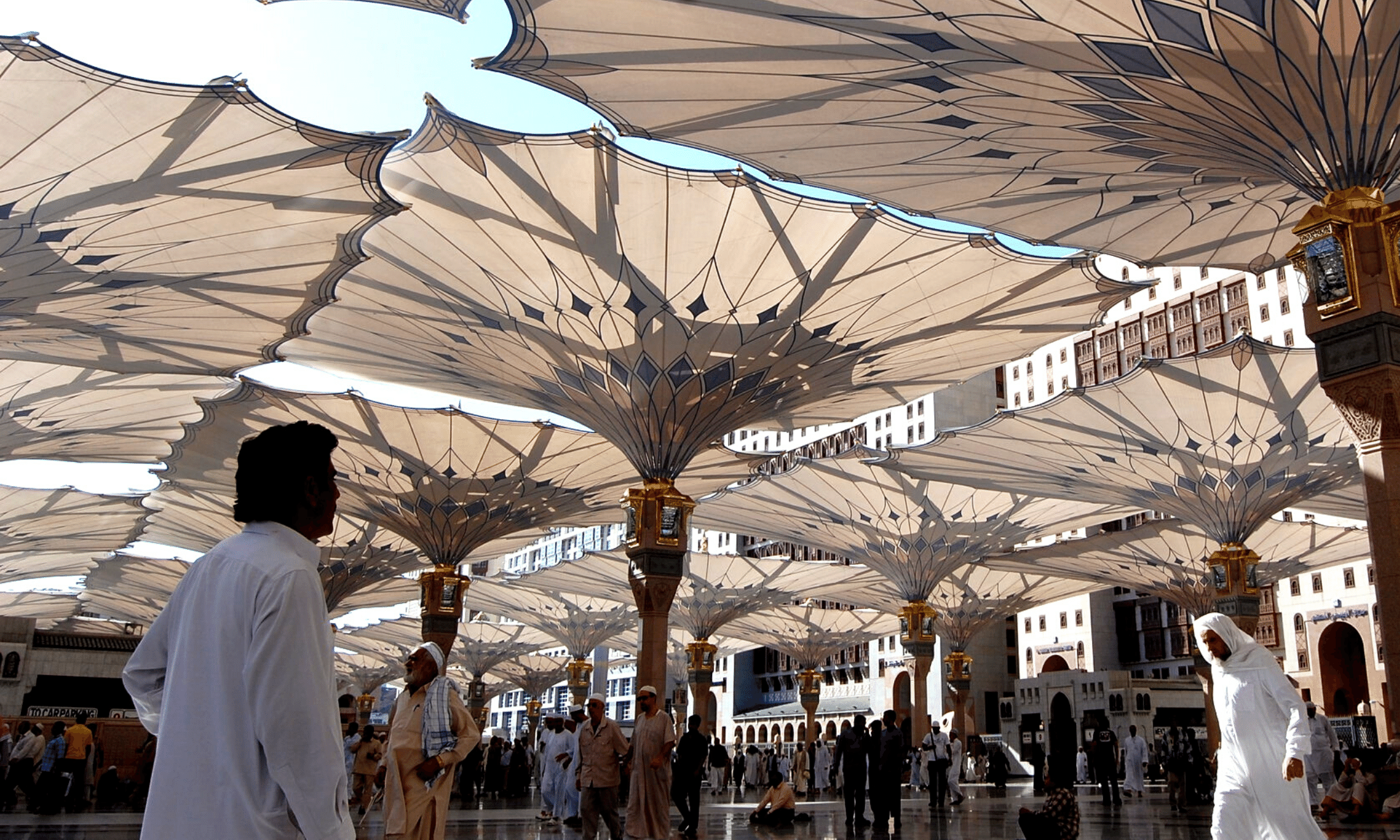

Image by Nina Manandhar

Audre Lorde famously wrote, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive”. Her conviction that oppressed people must define their own truths – often and especially through writing – is a practice that has emboldened generations of black feminists and exploited peoples around the world. Today, the fantasies that threaten to “eat people alive” exist in no less abundance than at other moments in history. For Muslim women, in particular, the images, narratives and rhetoric produced about us are so dense and overwhelming that the capacity to not be “eaten alive” can sometimes feel impossible.

Mainstream media is littered with repeated tropes of oppressed and submissive women needing saving, daily derision of hijabs and niqabs, moral panics about “British Values”, and “radicalisation” being accompanied by photos of Muslim women’s faces. The potential for those portrayals to “eat people alive” translates as mental health deterioration, lack of security and safety, attacks, harassment, racism and exclusion, the possibility of extreme isolation, and alienation. How then do young Muslim girls bear the weight of this?

A group of girls aged 11-14 from Wapping High School in Tower Hamlets do it by following in Lorde’s footsteps. They have produced a zine entitled, Battling Expectations, a collection of poems that came about as a result of the Muslim Girls Fence project, a collaboration between the charity, Maslaha and British Fencing.

Muslim Girls Fence works to facilitate space for girls, the majority of whom are Muslim, to challenge assumptions and narratives relating to their gendered, racialised, religious and other identities through both physical and creative avenues. The girls are coached to learn the traditionally elite and white male-dominated sport of fencing. Through this, they are able to physically confront the expectations of society: that Muslim girls are weak, subordinated and lacking agency. Alongside this, they engage in a range of discussions and creative exercises to reflect on their identities, stereotypes, and the limited sets of role models that are usually given a mainstream platform in society.

“Battling Expectations was created through a series of discussions around stereotypes, assumptions and identity”

The process that led to the creation of Battling Expectations was a series of discussions around stereotypes, assumptions and identity which led the girls to consider the disparity between how they define themselves, and how they are perceived by others – often citing tropes they hear about being housewives or terrorists, poignantly reflecting the way political rhetoric seeps into children’s playground insults. The zine itself was a product of exploring different methods of art for activism from protest posters to film, photography and poetry. In light of seeing the effects of such resistance Sara, Ariefa, Muskan, Soledad and Rose wrote their own poems resulting in the moving pieces included in the zine.

Battling Expectations stands in the face of Islamophobia and jingoistic debates around “Britishness” by platforming the girls’ narrations of their own stories. It also reinforces the value of their voices and the fact that they, who are so often deemed disposable and marginal, are in fact sources of knowledge and of artistic creation.

‘I am nothing like you think I am… my hands are the swords I use to break stereotypes’ – Areifa Rehman, 13.

‘You think I represent just a nationality, but my heart is who I am, and its pure personality’ – Muskan Ridi, 14.

Since the project, the girls’ teacher, Hayley Charman, has noticed that the girls have taken their voices and feelings outside of the classroom too – influencing the school more widely as well as galvanising them with confidence that they can achieve their aspirations. In the context of living in the borough with the highest rate of child poverty in the UK, as well as a wider environment of cuts to social, youth and mental health services, this demonstrates the crucial and transformative effect of facilitating spaces for marginalised girls to speak freely and on their own terms.

“Muslim girls in East London are confronted with the usual sexist tropes that “girls don’t play sport””

This project is especially important in the context of the government’s Prevent duty – a statutory measure placed upon education providers to “look out for signs of radicalisation” amongst students. In reality, the impact of Prevent is that the speech and thought of Muslim students has become increasingly stigmatised and criminalised in the UK, with less and less space for Muslim students to talk, debate or discuss freely. The situation is further politicised in light of the way Shamima Begum’s experiences have been narrated and exceptionalised due to her being from a working-class, Bangladeshi, Muslim community in East London. Subsequently, Muslim girls in boroughs like Tower Hamlets are not only confronted with the usual sexist tropes that “girls don’t play sport”, but much more insidious and criminalising rhetoric too. Muslim Girls Fence participants explain that these Islamophobic currents often manifest as offhand jokes and comments about terrorism in the playground.

Battling Expectations is, therefore, a reminder of the fact that young Muslim girls are not only aware of the biases and structural disadvantages they face in society, but that they refuse to accept them. Muslim girls refuse to be positioned solely as victims. Their poems engage the expectations that they experience in a range of ways, ultimately leading to the expression of their own identities through colourful metaphors and defiant similes. This itself is an act of protest: Muslim girls telling their own stories in a context where they’re so often merely tropes in other people’s narratives – from Ofsted to Boris Johnson – is radical and subversive.

Sara, one of the contributors to the zine, declared that the Muslim Girls Fence project has “given me more confidence and strength and power”. Clearly, Audre Lorde was right then: having the space to discuss identities and subsequently define ourselves, radically impacts our ability to exist on our own terms.

Not only do these girls confront and challenge expectations then, they ask the reader to respond and consider, how are you defining yourself for yourself? This International Women’s Day, how are you #BattlingExpectations?