Diyora Shadijanova

How I’m trying to outgrow old narratives of women’s sexuality in Pakistan

While sexuality is still seen as a young feminist’s issue in Pakistan, the tide is slowly shifting. One writer explains how.

Sandaleen Qaiser and Editors

02 Dec 2021

The term ‘sexuality’ connotes a vague danger in Pakistan. It is an instigator of violence, an object that needs to be hidden away. At times I find it difficult to think about my sexuality outside of abstract terms. I used to experience it as something tethered to social concepts like ‘honour’ and ‘purity’, to this sense of it serving a greater purpose than myself, because this is how it was often presented to me. Rarely was it about personal desire or the men I’m attracted to. There was always an underlying notion that my sexuality and my desires did not entirely belong to me, but to others.

When I got ready to graduate high school with top grades and university offers under my belt, the first thing a family member told me to do was go back indoors and cover my arms. I remember the shock of it. Everything else I had achieved up until that point felt reduced to rubble just because I’d chosen to wear a sleeveless top and, perhaps aptly for the emotional occasion, I spent the ceremony trying to hold back tears for the wrong reason. My family member was embarrassed for themselves. Baring my arms, which to them meant I was signalling my sexuality, somehow dishonoured them.

“Baring my arms, which to them meant I was signalling my sexuality, somehow dishonoured them“

Five years on from the Qandeel Baloch murder, it has become increasingly apparent that viewing women’s sexuality as a communal property that signifies ‘honour’, rather than an individual identity, is a pitfall. I live in Islamabad, a capital city that houses the full political spectrum from progressive secularists to religious conservatives, all of whom reacted strongly to the recent spike in reportage of the ongoing femicide in the city and beyond.

When women are subject to any form of violence, the conversation inevitably turns to her ‘dishonourable’ behaviour. Why was a woman out on a motorway with her kids at night? Why was Noor Mukadam at her killer’s house if she wasn’t married to him? Why was Ayesha Akram making TikToks in public when there were 400 potential harassers around? The argument rests on the double bind that we are both vessels of purity expected to behave asexually, yet must always be aware of our supposedly dangerous sexual nature.

“When women are subject to any form of violence, the conversation inevitably turns to her ‘dishonourable’ behaviour”

For other Pakistani women and I, the constant reminder that our sexuality poses a threat to ourselves and to the community is exhausting and draining. Most of us resist and react against these arguments when they are posed both online and in person. But because of the threat of violence, it’s mostly online through chats and support groups that we create our own space to share our side of the argument. And it is also online and through private research that I’ve come to an understanding of my relationship to sexuality, and an understanding of purity as the socially manufactured idea that it is.

During the British rule of South Asia (1858-1947), women who veiled were almost exclusively upper-class and used purdah (the Muslim veil) as a symbol of their status. They were described by European onlookers as sexually repressed, which became part of a larger agenda, a popular moral justification for British imperialists who branded themselves as saviours. Many have pointed out the eerie parallels with the recent American concern for Afghan women, used as a justification for the US occupation. As Anindita Ghosh details, South Asian women were constructed under successive nationalist governments as symbols of perfect purity who needed protecting and concealing from the corruption of foreign influence. If we look back over modern history then, we see how Pakistani women have been cast in the perpetual position of having their sexuality written for them, both by colonialists and then by nationalists.

“Many women like myself see through the binary of nationalist and colonialist ideas about our sexuality”

Realising that Pakistani women have been mythologised as ideological emblems for so long has brought to light why I and many of my friends internalised false narratives about our sexuality. It is the reason some conservative women will resort to victim-blaming, or why some liberal women might lean on the elusive dream of the West as the source of sexual liberation. But I suspect that many women like myself see through the binary of nationalist and colonialist ideas about our sexuality. Instead of leaning on them, I try now to look inward.

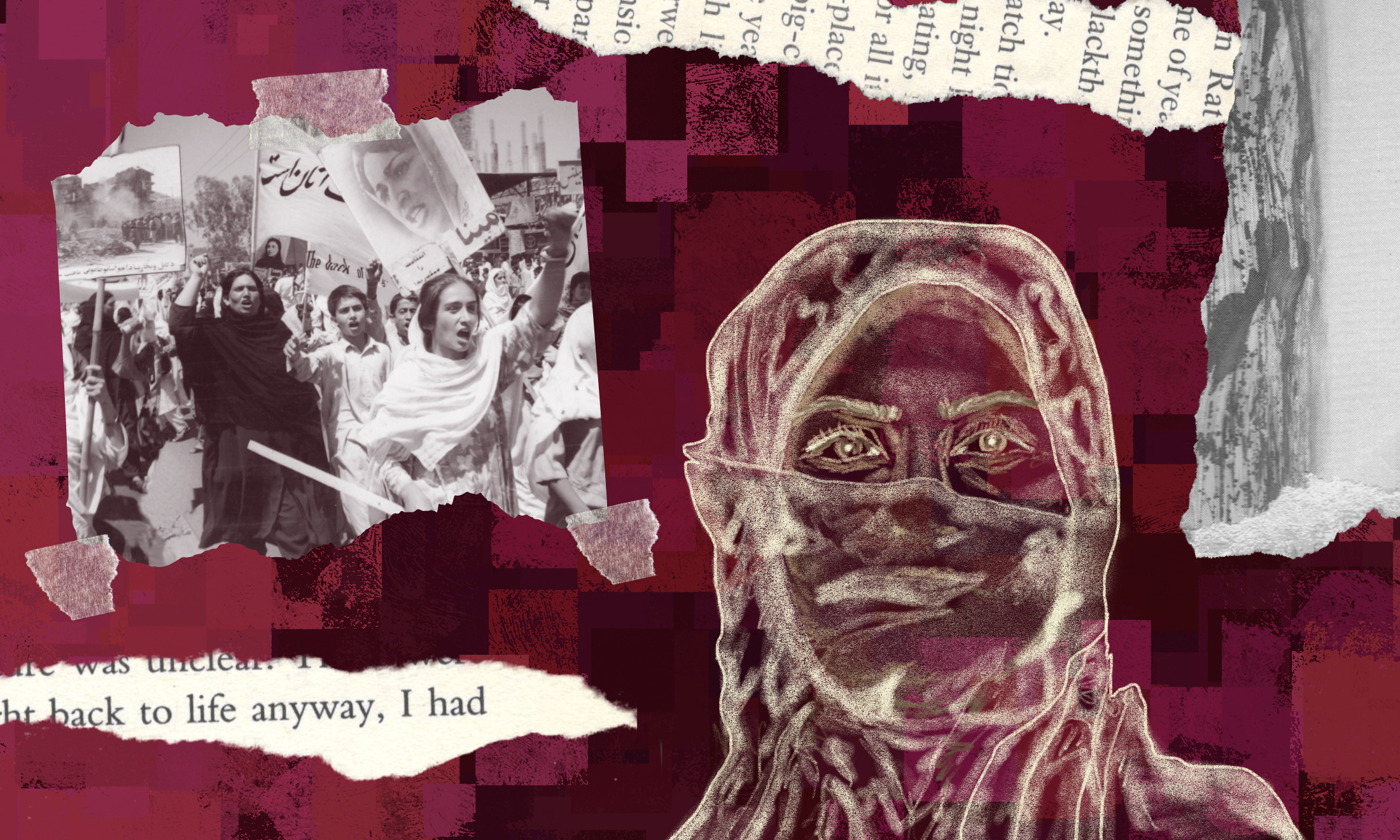

While sexuality is still seen as a young feminist’s issue in the country, the tide is slowly shifting. Pakistan’s Aurat (Women’s) Movement, since its inception in the 1980s, had to tread cautiously to establish its arguments in the Islamic context. The Movement’s focus on grassroots organising, building ideas from the ground up rather than relying on foreign intervention, has been one of its most important features.

I believe it is what has allowed a new generation of self-empowered women to emerge. The movement’s slogan mera jism meri marzi (‘my body, my choice’) was initially branded by opposers as contentious, the movement irreligious. Yet, I see a surge in the confidence with which Pakistani women express in everyday conversations a desire to be bolder and unabashed about their bodies and their sexuality. Together, we are outgrowing external expectations of purity, and giving ourselves permission to self-define.