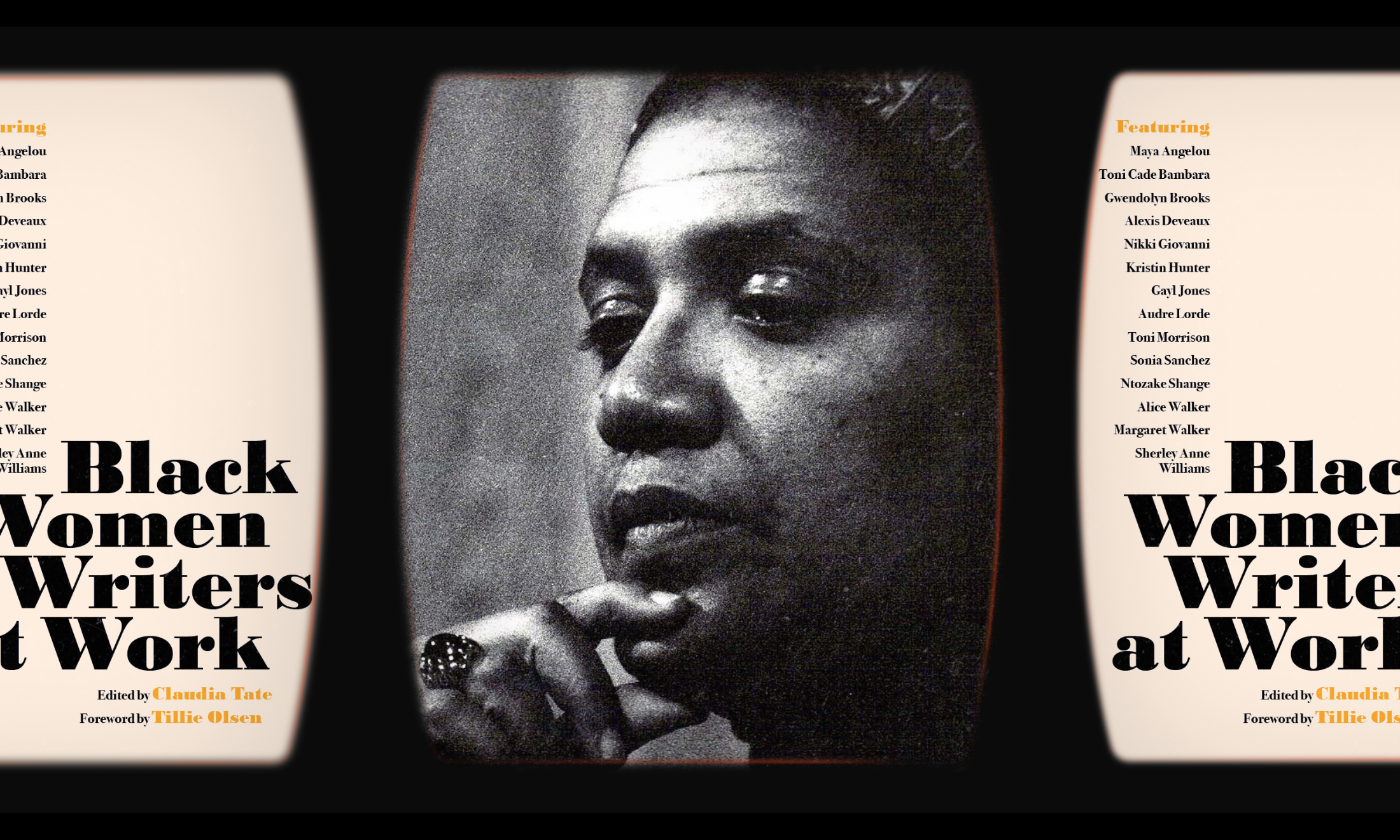

Courtesy of authors

Against borders: who counts as a spouse in hostile Britain?

Removing borders would allow people to move and access rights without having to expose their intimate lives to immigration officers, Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke de Noronha write in their book ‘Against Borders: the Case for Abolition'.

Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke de Noronha

19 Jul 2022

A camera crew follows immigration enforcement officers as they interrupt a ‘sham marriage’. In the middle of a low-key civil ceremony, agents intervene to prevent the ‘immigration offender’, a Pakistani national, from marrying the ‘fake bride’, a Slovakian national. The man is put in handcuffs and arrested, while the woman is interviewed to determine whether she was marrying for cash or was in fact duped by a fake romance. The details and the locations vary, but the stories are much the same. BBC News, Sky News, Channel 5 and other outlets filmed similar shocking exposés in the early 2010s, forming part of a moral panic about so-called sham marriages. These stories were not only about migrants cheating the system; they focused on the abuse of the institution of marriage.

In immigration law, as in civil law more broadly, primacy is given to marriage. Marriage is a way to make one’s relationship legible to the state. For non-citizens seeking rights, marriage can be an important avenue for claims-making. In British immigration law, people on certain visas can apply to bring dependents – spouses and children, for example – while other non-citizens can make immigration applications on the basis of relationships with spouses resident in Britain (although the Home Office has made it difficult to ‘switch visas’, for a temporary worker to switch to a spousal visa, for example). Migrants who are not married can still make claims to family life with a ‘qualifying partner’ (usually a citizen), but this must be shown to be a relationship ‘akin to marriage’ – which means cohabitation, shared financial responsibility and, of course, monogamy.

Clearly, marriage remains the ideal, and something that must be protected. Indeed, it is because some people apparently use marriage to secure their stay that marriages involving non-citizens are subject to inspection and surveillance. Hence all the shocking sting operations revealing the scourge of ‘sham marriages’. As a result, non-citizens now need to receive clearance before they wed, surveilled from the beginning.

“Leaving a relationship means becoming undocumented, and potentially facing deportation”

Since 2012, the UK government has stipulated that British citizens must earn at least £18,600 a year if they want to bring a non-EU spouse to live in the UK (requiring another £3,800 for a first child, and £2,400 for each subsequent child). This effectively prevents people on minimum wage from bringing their foreign spouses to the UK, and has particularly marked effects for women, especially ethnic minority women. Put bluntly, “it is virtually impossible for unemployed or disabled people on benefits to marry a person from outside the EU”.

Around the same time, the British government extended the probationary period for spouses from two years to five years, apparently “to test the genuineness of the relationship”. This means that if a couple splits within those five years, the migrant spouse does not have the right to claim settlement independently. Unsurprisingly, this has had the effect of trapping migrant spouses in unhappy and sometimes abusive relationships, where they are effectively dependent on their citizen spouse for their residence. Leaving a relationship means becoming undocumented, and potentially facing deportation.

People on spousal visas in the UK are usually subject to a policy that stipulates they have “no recourse to public funds”, which means that they cannot legally claim welfare benefits – including Disability Allowance, Housing Benefit, out-of-work benefits and Child Benefit. This makes migrant spouses especially dependent on their sponsoring partners, because they will be rendered destitute if they exit relationships.

The exclusion of non-citizen spouses from social rights, combined with the threat of deportation, thus creates the conditions for abuse. One key non-reformist demand would be to ensure that such migrants can claim rights independently of a spouse (and indeed of an employer), so that everyone has a means of exiting situations of domestic abuse or workplace exploitation.

Abolitionist demands focus on reducing the reach and force of immigration enforcement – which in this case extends into people’s intimate and family lives. That means less surveillance, inspection and conditionality surrounding marriages, as well as the extension of rights to individuals independent of their relationships to spouses. More ambitiously, it means dethroning the marriage relation altogether by allowing people to move and access rights without laying their intimate and personal lives out for bureaucratic scrutiny.

This edited extract is taken from Against Borders: the Case for Abolition by Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke de Noronha. Published by Verso, it is available from 19 July here.