Aluna Francis on Beyoncé, the ‘oonts oonts’ resurgence and Black women’s place in electronic music

‘Renaissance’ gives us time to reflect on the visibility and exploitation of Blackness within dance genres.

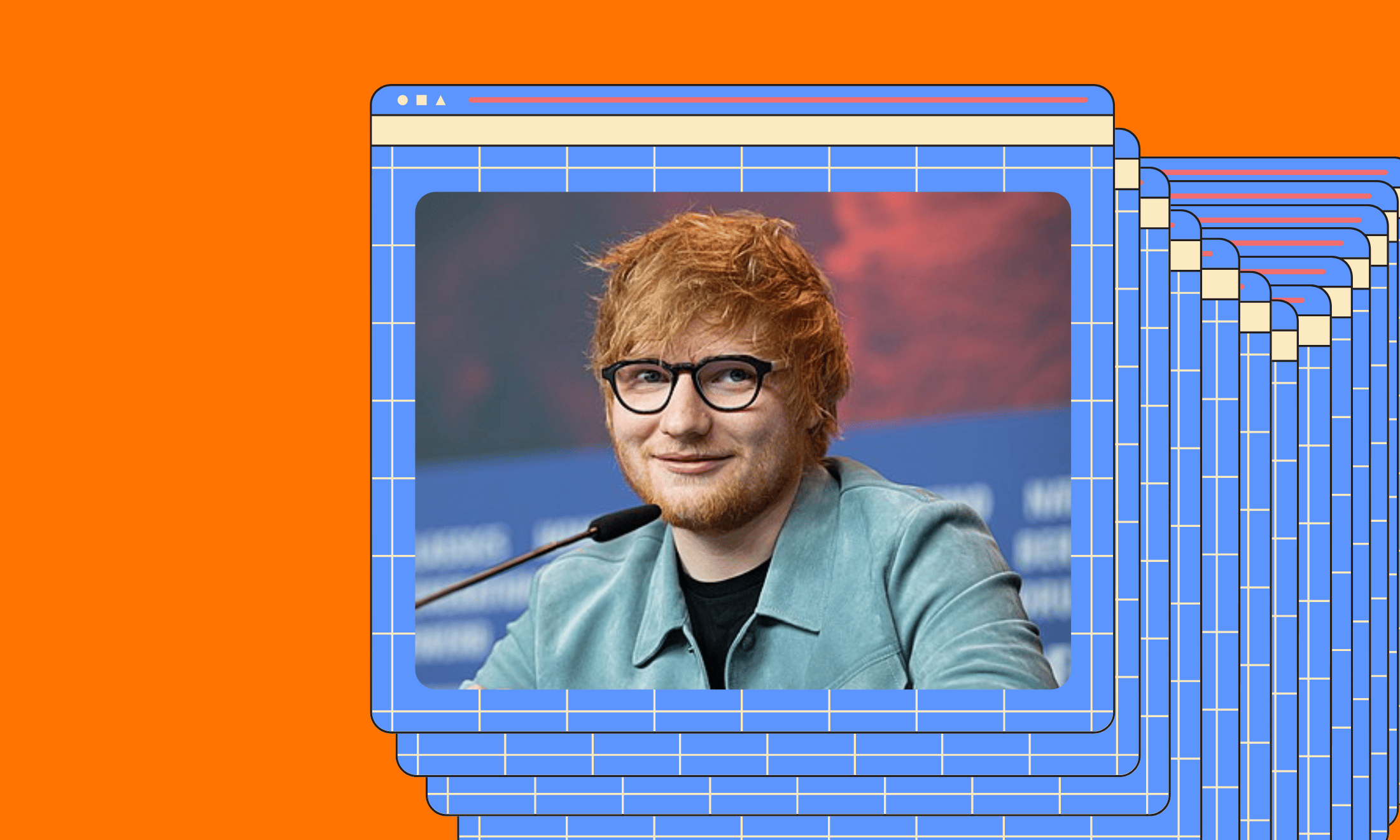

Aluna Francis

12 Aug 2022

Merc Photography

I’m sitting in a café with ‘Break My Soul’ on the speakers in downtown L.A. wondering what’s going on. This time last year, I was fiercely pushing against every obstacle that stood between Black communities and us thriving in electronic/dance music, and now it seems like the huge shift I was hoping for is upon us.

With Honestly, Nevermind and Renaissance on the airwaves, for the first time in my career the stigmas around dance music are being disrupted with a message reaching across the globe – “dance music is Black” – and this time it’s not just the echo of my voice not being listened to. As individuals and small communities (often in the underground), we’ve been doing what we can to hold on to our legacy and pioneer the future sounds of these genres. But if we were ever going to make significant changes to the current mainstream culture, it would require the hardest players in the game to join the cause.

Having contributed to dance music since 2014, as part of the AlunaGeorge duo, then as a solo artist from 2020, I consider myself both on the inside and outside of the genre – a position that gives me a unique perspective. Although I’ve generated over a billion streams, have featured on songs including Disclosure’s hit ‘White Noise’ and performed at some of the largest electronic music festivals in the world, as a Black woman, I’ve had no real “place” as a main artist other than being the faceless voice and soul of music that has uplifted the careers of other people. I just don’t fit the profile (white, middle class male).

“As a Black woman, I’ve had no real ‘place’ as a main artist other than being the faceless voice and soul of music that has uplifted the careers of other people”

That being said, I made the decision to go solo in this genre, rejecting the binary view that had for so long framed my career: Black people make hip-hop, soul and R&B, while white people make country, rock and EDM. And anyone who deviates from these rules, like me, is an anomaly. In 2020, I was willing to fight all that with my debut solo album Renaissance to create visibility for Black women in the genre and reach the audience who also want to see us thrive.

Since amplifying the conversation on the lack of diversity in the dance music industry, I’ve looked at all the various reasons that brought us to where we were two years ago when I released my first dance album: the eradication of the Black history of dance music happened systematically: the consistent policing and shutting down of Black and LGBTQI+ gatherings meant that we were no longer able to create the spaces for marginalised communities to enjoy dance music. For example, Section 28 in the late 1980s in the UK banned the “promotion” of homosexuality. It mainly affected schools but also allowed the police to monitor and target LGBTQI+ and Black gatherings, shut them down and prevent further events.

“The lack of diversity in dance music can also be attributed to the financial investment exclusively into white male producers by labels and festivals promoters”

The lack of diversity in dance music can also be attributed to the financial investment exclusively into white male producers by labels and festivals promoters (look at the top highest paid DJs and dance artists in the world), and the cronyism that led to their continuous support from radio, digital streaming platforms and the media turning them into global superstars, for example, David Guetta was named the “Grandfather of Electronic Dance Music” by ABC News in 2018. Moreover, there has been constant genre policing, shown through the lack of representation of genres such as Jersey and Baltimore club, maintaining the Eurocentric criteria of what qualified as mainstream dance music, leaving most styles Black origin out of the picture.

While the mainstream dance/electronic genre has remained firmly devoid of diversity from the outside, Black women have been the often uncredited or invisible voice and soul of mainstream dance music through the decades. Loleatta Holloway on “Ride on Time”, Martha Wash on “Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now)” and Jocelyn Brown on “The Power” in the late 1980s and early 1990s are widely documented for the uncredited exploitation of their voices, setting a precedent that Black women’s voices exist to be used freely by any producer who feels like it.

In recent years, artists like Elisabeth Troy, Shingai and Kelli-Leigh have had to fight hard for fair accreditation and most Black women artists I speak to are constantly being asked to feature on tracks and rarely invested in as solo artists. I have often featured on tracks where my face is nowhere to be seen so nobody even knows I’m Black. When I read “the narrative is that we don’t sell records” in an article, that statement struck a chord. This is the culture we are used to.

“I have often featured on tracks where my face is nowhere to be seen so nobody even knows I’m Black”

Black dance music producers around the world have pioneered different styles of dance music like dancehall, UK garage, drum and bass, Afrobeats, Gqom, and most recently, Amapiano. Such artists have fed dance floors around the globe, but are usually categorised outside of mainstream dance music across streaming platforms. Many of the original Black producers who pioneered the genre have steadily continued to release music and play the live circuit such as Carl Cox, MK, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick Carter, Green Velvet (aka Cashmere) and DJ Paulette, yet you won’t see them in Top 10 Electronic Dance artist lists very often.

Black women such as Noelle Scaggs from the Fitz and the Tantrums have worked tirelessly to overhaul the lack of diversity in live show production and agencies with ‘Diversify the Stage’. Kelli-Leigh created a guide with MU and FAC to help singers learn how to make sure they are correctly credited. I have worked with distribution and streaming platforms like Spotify and Amazon Music to address miscategorisation and representation in playlisting – now Club music is listed under Dance/Electronic category on Spotify.

I also created a support group for Black ravers, as well as a TikTok campaign to amplify and connect them with others so they realise they’re not alone. Through this coming together we spoke extensively about what we desired to see change in mainstream electronic dance music festivals and the culture around them.

“Rather than waiting for mainstream festivals to expand their lineups, I set out on a mission to create one with an all-Black lineup”

Rather than waiting for mainstream festivals to expand their lineups, I set out on a mission to create one with an all-Black lineup, something I hadn’t experienced or seen. So in 2021 Noir Fever New Orleans was announced in partnership with Pollen, and was set to take place in May 2022.

The difficulties with putting on a brand new festival are already complex in this post-pandemic period, but the need for variety in what dance music festivals have to offer pushed me to try to navigate this unchartered territory anyway. The vision I have of seeing Black dance artists thriving in a space designed for them is an irresistible call. I’ve seen what can happen when people feel welcome and safe. After coming up with the concept for Noir Fever, my team and I partnered with Pollen and worked with them for almost two years on it. I had booked some of the most accomplished and cutting-edge dance artists in the game – good friends and people I respect, with the idea we were changing history.

“It makes me wonder if they ever intended to deliver or if this was indeed a prime example of a performative act”

Pollen seemed to benefit greatly from the press around the launch of Noir Fever, as they then went on to raise a new round of funding. After securing their round, communication with them leading up to the festival date felt as though it began to stall as I was met with pushback on calls with the team when suggesting new initiatives and plans, only for them to ultimately postpone Noir Fever at the last minute.

It makes me wonder if they ever intended to deliver or if this was indeed a prime example of a performative act. On 9 and 10 August, multiple reports indicated that Pollen had collapsed into administration, refunds to customers had been delayed, and the company had repeatedly missed payday for its 500 staff. [Pollen did not reply to gal-dem’s requests for comment.]

We will throw the Noir Fever festival in the near future, though this experience has shown me the need for the passion for change to come from all the way up the food chain, so our next partner will need to want this as much as we do.

As I’ve looked to contribute to a different reality for the future of this genre, I’ve been paying a lot of attention to the communities who have already created safe spaces all over the world for Black dance music to thrive. The impact of Drake and Beyoncé dropping their albums could have a really positive effect on the investment and growth of those communities.

That’s the real renaissance; the beginning of an era where the rightful place of the Black woman in electronic dance music is at the forefront, ready to say “you won’t break my soul”.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!