Photography courtesy of Disney+

Coming to America and Modern Maasai: the hidden references of Beyoncé’s Black is King

All the symbolism you may have missed from the Disney+ visual feast

Natty Bakhita Kasambala

04 Aug 2020

It will come as a surprise to nobody that we’ve been saturated to the brim with discussions of Beyoncé’s Black Is King. But the one-hour and 25-minute film is a visual odyssey of sound, textures and movement inspired and soundtracked by the 2019 album The Lion King: The Gift, curated by Queen Bey herself so buckle up for another.

From diamond-encrusted outfits twinkling in the blazing desert sun to 20-deep squad of leopard-clad men equipped with a matching Rolls Royce. It is immensely beautiful. The visual feast sees Beyoncé make an epic 69 costume changes throughout amidst additional breathtaking setups in the desert, in forests, over bodies of water. With special appearances from most of the album features including Pharrell, Tiwa Savage, Yemi Alade, Shatta Wale, Tekno, Mr Eazi, Tierra Whack, Busiswa, Nija and of course Blue Ivy, it was a meeting of diasporic minds that showed we are not a monolith.

Much like the album, this film took a truly pan-African approach to its representation highlighting artists, creatives and designers from across the diaspora. Featuring the work of Britain’s own filmmaker Jenn Nkiru, writer Yrsa Daley-Ward and cameos from Cktrl’s Bradley Miller, Nula’s Diane Nadiah Adu-Gyamfi and illustrator Jasmin Sehra amongst many more. And with so much to unpack and digest from the film visually, venturing forward into Afrofuturism as well as touching on striking practices such as Namibian red clay hair braiding or the universal journey of women from rivers with calabashes full of water, there are probably many images within Black Is King that are otherwise unseen in the ‘mainstream’ today, while others are more familiar. Here are some of our favourite references throughout the film that you may have missed:

Coming To America Africa:

Say what you will about Coming to America – heck, say what you will about Black capitalism – but this scene from the 1988 film starring Eddie Murphy will be forever ingrained in our collective memory. Murphy’s character is awoken from his deep slumber in pink satin sheets by a live orchestral alarm clock. He is then bathed (giving us the line: “the royal penis is clean your highness”) and his teeth are brushed for him as he is waited by servants in his palace in the fictional African nation of Zamunda. His everyday routine. Beyoncé recreates this iconic scene soundtracked by the sweet lullabies of Malian mammoth Oumou Sangare, waking in a mansion as her husband pulls up to the estate: teeth brushed by an old white male butler as her grills glisten.

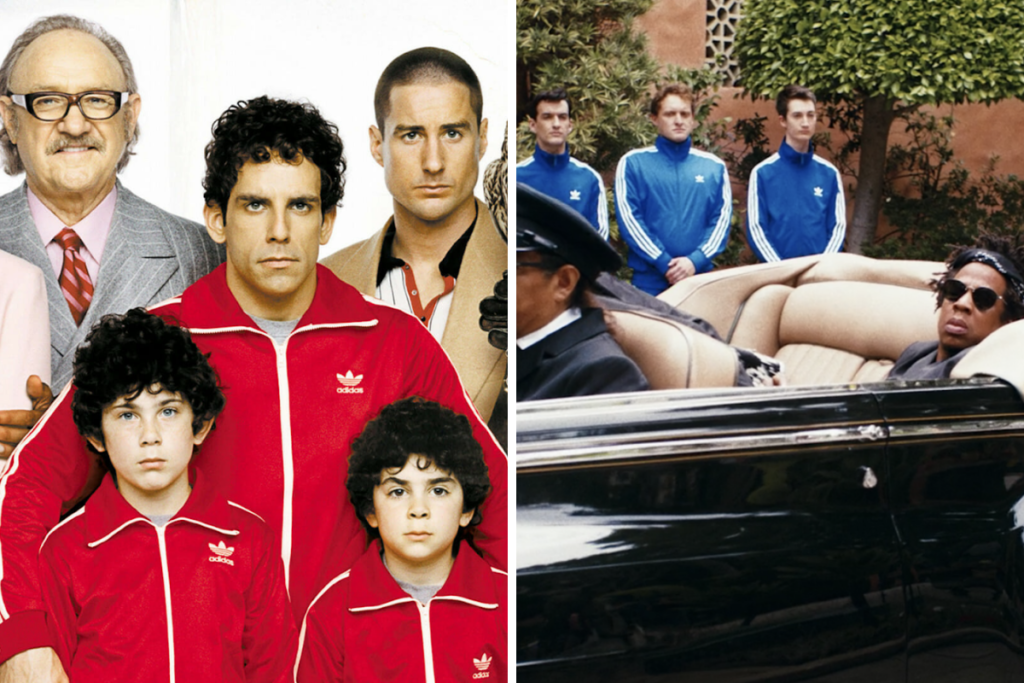

The Royal Tenenbaums, à la Carter:

In the same scene, as Beyoncé’s husband Shawn Carter arrives at the mansion in style, three men can be seen to be waiting to receive him at the front of the house, dressed in matching blue Adidas tracksuits. Given the decidedly editorial nature of most of the fashion throughout the film and the natural and printed tones for this scene, in particular, this decision sticks out immediately. Only when Jay-Z enters the house and starts performing his verse to the camera does the reference become clear.

Inside in his office, Jay is dressed in casual sportswear with a headband and suit atop, in the exact fashion of Luke Wilson’s character from Wes Anderson’s 2001 film The Royal Tenenbaums. It’s a comedy-drama about an insanely privileged family and their toxic interpersonal relationships. The key joke of the film’s title is that rather than it being about a family that are actually descendants of monarchy, the father’s first name just happens to be ‘Royal’. Here, the Carters subvert that wordplay through their own dedication to language of Black as royalty and glory and the like.

The Modern Maasai:

One of the most striking images for me came with the crowd of black men in suits recreating an East African tradition. The tradition is known as “adumu” which translates roughly to mean ‘jumping dance’ and is performed by Maasai warriors – members of the ethnic group that originate from Kenya and northern Tanzania. The iconic jumping is usually done in circles and as a form of competition with members of the group reacting in song with the highest jumps. The ceremony has become something of a staple within the Kenyan tourist industry but is a rite of passage and show of strength and skill for young warriors.

Biblical Bey:

At just past the halfway mark, there is a sonic shift as an impending sandstorm threatens to bury a small town. We see Beyoncé here as the mother of a small baby for the second time, singing sweetly in a modest room cloaked in dusk robes. She makes her way down to the river with her baby and begins to cry as she places him in a basket. This reference is one of the more obvious, harking to the biblical story of baby Moses, placed in a basket in a river to save his life. He is later found and becomes Egyptian royalty. It’s fair to say this tale of promise and the story of Exodus since became a bastion of hope within the African-American community during the times of emancipation. The spiritual “Go Down Moses” is even believed to have been written in the 1800s by slaves inspired by the biblical ‘redemption’ story. Here in Black Is King, the journey is one of hope too. The basket travels through the choppiest of waters only to be found by a new iteration of Beyoncé who is dressed in luxurious white robes. Salamishah Tillet writes, “the waters here also invoke the Middle Passage, with each ripple break recalling the fateful journey in which New World slavery, and America itself, was born.” In this sense, the journey of baby Moses here is a hopeful reimagining of travelling far, in order to return home.

Subverting the gaze:

The last is a broader point of the consistent subversion of power dynamics and reclamation of aesthetics throughout the film. From the country house to the renaissance supper table or the synchronised swimming sequences, it’s clear that Black Is King sought to fill historically White Spaces with an unfiltered, unapologetic Blackness. Not because ‘rich’ Black people are so unheard of or to yearn for respectability and upward social mobility within the current structures – African-American debutantes, for example, have been happening for decades – but I think the statement is made more to disrupt. To depict the full breadth of possibilities for Black people not just in America but across the entire diaspora, to offset the often complex relationship between Africa and its descendants across the globe.

One of the main criticisms of the work, and at times of Beyoncé and Jay-Z more generally, has been the focus on luxury: the celebration of Black billionaires in a world where Black capitalism is still a system of oppression. To that, I would concede but suggest that while ultimately the aim of progress cannot be monetary, there is still value in seeing this as a symbolic reshaping of what Blackness connotes in the mainstream. Being able to visualise our people in these spaces as a source of release and disturbance. In the same way, her inclusion of all-white service workers should not be taken literally as a goal to oppress all white people, but as an extreme disturbance of the norm in order to shake the rigid structures loose altogether.

Celebration as an antidote colourism:

One of the most triumphant aspects of Black Is King for me was the constant centring of Black women, especially dark-skinned women, throughout the film. Often overlooked and erased in conversations around diversity, the significance of the casting cannot be understated. The peak of this representation came to a head during the sequence for Brown Skin Girl, a song that Beyoncé initially received backlash for due to her naming mostly dark-skinned black women in the lyrics. In the visual, she doubled down on the message featuring the likes of Lupita Nyong’o, Naomi Campbell, Kelly Rowland, Adut Akech, Aweng Chuol and more.

Amongst many, there was an especially beautiful moment that featured a dark-skinned South Asian woman amongst the line up, an often marginalised contingent in discussions of colourism. You only have to look to Netflix’s popularised show of the moment Indian Matchmaking to witness the normalisation of attributes like ‘fair’ when discussing ideal partners. Other dark-skinned Asian women also feature throughout other scenes of the piece too.

The imagery of Ifa:

Alongside explicitly describing herself in the narration as “sister of Naruba, Osun, Queen Sheba, I am the mother” during MOOD4EVA, Beyoncé consistently uses imagery to align herself with the Yoruba goddess or spirit. Symbolising love (*check*), water (*check*), sensuality (*check*) and fertility (*check*) there’s a clear line to be drawn between the themes of the film and Beyoncé’s practice of the Ifa religion here. As a result of the Easter eggs, many on the interwebs now believe her to be an Ifa practitioner in fact.

Adinkra symbolism:

During the vibrant performance of anthem ‘MY POWER’ the camera hovers above at intervals to showcase a mix of markings and body shapes that resemble Adinkra symbolism. These are visual symbols used in art, fabric patterns and even architecture, originally created by the people of Gyaman, in what is now modern-day Cote d’Ivoire. And though this may seem like a little bit of reach in isolation, upon researching it’s clear that the particular symbol in question here translates to mean wealth or abundance. A key theme throughout the visual piece.

The Mursi women of Ethiopia:

While the #illuminaticonfirmed contingency of Twitter debated the significance of the statuesque horns Beyoncé wore in the film, claiming that they were an ode to her alleged devil-worshipping and linked to the Satanic deity Baphomet, the symbolism here felt closer to the Mursi women of Ethiopia. They’re more commonly recognised for their striking use of lip plates in the lower lip. While poised on a horse in a room clad with hide, Beyoncé holds a traditional smoking pipe, adorned with cowrie beads and the horns wrapped in her own braids. It is an ode to the resourceful and natural beauty that’s rife within the continent.

All hail King Childish Gambino:

Despite starring as Simba in the Lion King remake, and multiple appearances on the accompanying album, Childish Gambino is notably absent from Black Is King… or is he? During the opulent feast in MOOD4EVA (the song he features on), there is a full-size painting of him hung up in the background at the kid’s table as they raise their goblets of milk.

Black is King is available to stream on Disney+ now.