Photography composite via Canva

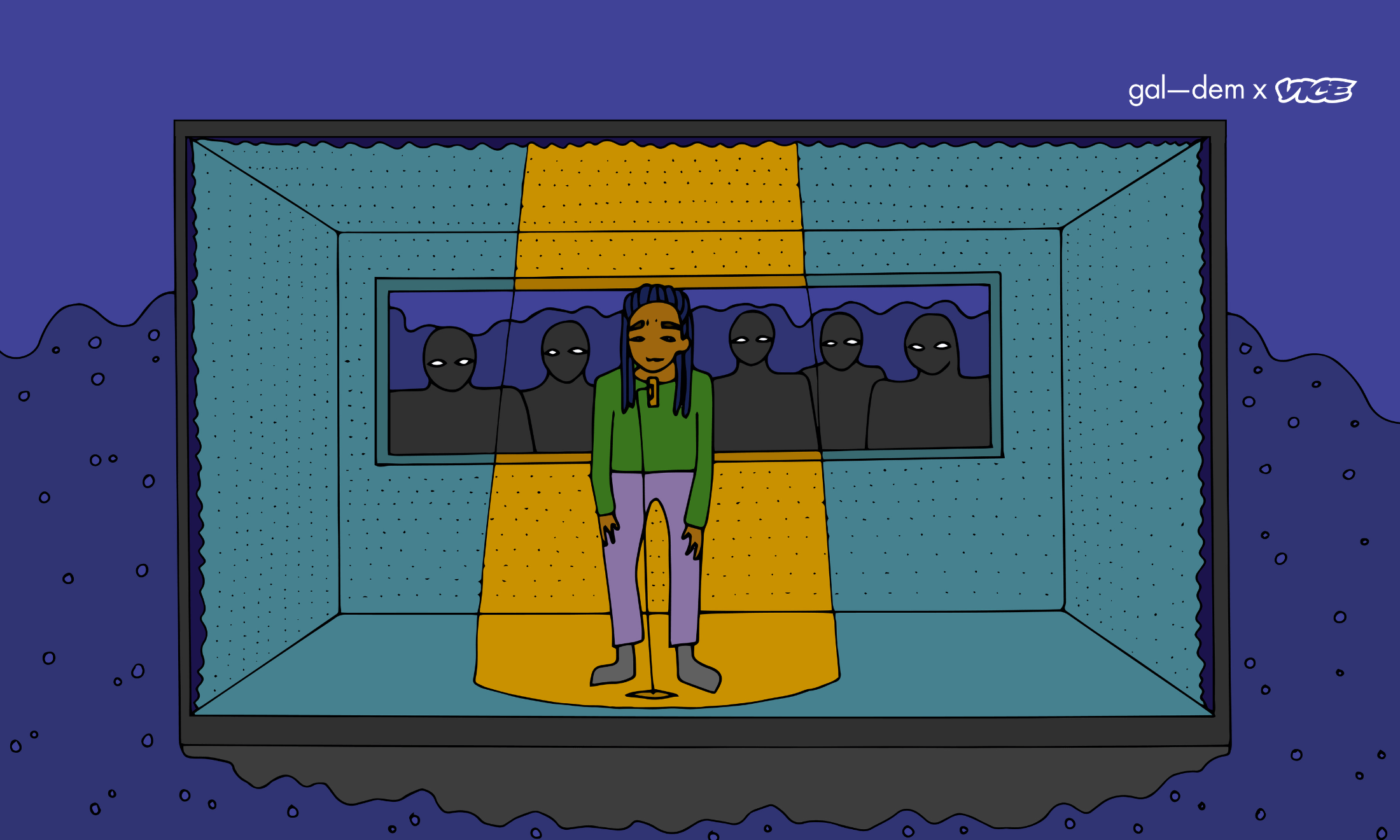

Can black artists counter music industry exploitation?

It's becoming clearer than ever that the music industry doesn't look after its black artists. From Megan Thee Stallion's recent decision to sue her label to TLC's infamously unfair contract, Danielle Koku explores the dark underbelly of a glamorous profession which sometimes holds artists to ransom – and speaks to those who fighting to protect black talent.

Danielle Koku

25 Mar 2020

Scrolling past tedious, drawn-out pages of obscure terms and conditions without paying much attention is easy for anyone who looks at a screen at least twice a day. For musicians, however, reading and signing contracts is closer to running a gauntlet – and, especially for black artists, it’s not for the faint of heart.

90s megastars TLC’s notoriously appalling record deal left them millionaires for roughly five minutes before their amassed fortune was carved up by percentage cut after percentage cut for middlemen and labels. More recently, the souring of Houston hottie Megan Thee Stallion’s deal with record label 1501 not only exposed the insidious side of an industry which often cares little for artists’ wellbeing, but equally how much a badly-timed dispute can stall releases at an artist’s prime.

“Poor deals are not only an ethical matter, but something that questions the future of a music industry that struggles relating to new black talent outside exploitation”

Stories like this are not few and far between among black musicians. Tinashe’s label trouble follows a similar trajectory, as well as Frank Ocean’s eventual victory over Universal Music and the beloved Prince’s never-ending legal battles with Warner Bros. Between retaliation, the blocking of future releases in court and the chances of being left high and dry after it all, some artists are understandably left asking whether it’s worth entering the big shiny boardrooms in the first place, only to be the subject of a “#Free [insert artist’s name]” campaign after a year.

Poor deals are not only an ethical matter, but something that questions the future of a music industry that struggles relating to new black talent outside exploitation. Fortune is a trickily-managed path past the talent and sheer luck it is so often reduced to, and loss often comes in the stroke of a pen for the unsuspecting. Speaking to industry voices on the matter made it clear that navigating the industry is a finely tuned skill.

Why do artists want a record deal in the first place?

Fame is often envisioned as the big, glittering screens facing crowds of thousands who are chanting your lyrics. Understanding the reality behind the glamour is closer to a maze in which the walls move, sometimes with notice, but often without. Bad deals are an ugly side of the game and part of a much uglier beast altogether.

Signing to a label is the perfect way for many artists to finally gain some financial dividend. “Going clear” or “blowing” are just some of the informal terms used to capture the scale of change that surrounds an artist once they hit the big money. All of a sudden, things become easier. Things are “handled” for you, stuff is “taken care of”. The benefits that come with signing are not small and, for some black artists coming from economically-deprived backgrounds, it often makes more financial sense to scale things up, with the promise of making a return for the label further down the line.

Exploitation isn’t inherently built into label relationships – the way in which it manifests points towards an industry-wide problem of uncertainty on how to bridge the gap between artists who could lose out on a promising career because an executive doesn’t approve their vision and labels aiming to maximise return on investment by commercialising an artist’s appeal. The disjuncture between two conflicting interests leaves space for loss – often, on the artists’ side.

The manifestation of exploitation

Black artists rank highly for visibility. Yet, this cultural currency doesn’t carry over when viral videos stop circulating and catchphrases stop being used. Jalaiah Harmon, the 14-year-old creator of the viral Renegade dance that took the US by storm this year, was initially sidelined for the positioning of more “media-palatable” dancers doing her Renegade in NBA matches and commercials.

Similarly, former Fifth Harmony member Normani Hamilton confessed that it was only following the group’s split (initiated by their label focusing on driving Camilla Cabello’s success as a solo star), that she felt more able to show her “truest” self. Normani’s ensuing success in the charts speaks for itself.

“If someone has set out to fuck you over, then that’s what they’re going to try and do”

– Alexandra Ampofo, live music booker

One thing is clear – the exploitation of black artists is not a matter of circumstance. As much as it can happen to anyone and their unsuspecting mother, it isn’t just bad luck. There is a reason that the majority of bad deals are handed to black artists who don’t have the financial backing to have their contracts sifted through and renegotiated.

The question of interest comes into play here because if an “upcoming” artist simply doesn’t possess the economic or legal capital to adequately protect themselves, then should they be entering the negotiation room at all? After all, it was only after Megan’s management re-signing to billionaire label RocNation that she was able to hire lawyers to request her old deal with 1501 be renegotiated. The cruel irony in her only gaining true understanding of her creative suppression once she had tied her future to yet another company of execs paints the game as one you just have to keep on playing, whether you like it or not.

It’s not as simple as heeding the warnings of those who have gone before you or getting a lawyer hired by and for a label to reread a few clauses either. If a negotiator is not themselves committed to transparency and equity as a principle, signing a deal that is at all fair becomes near impossible.

How artists are navigating this dynamic

With all this in mind, putting distance between their music and the boardrooms is a logical reflex for emerging artists looking to protect themselves. The diversification of services available to artists means that there are now separate agencies responsible for management, PR, distribution and touring – which all means they can retain independence whilst outsourcing the legwork of day to day logistics to separate companies. In this way, their artistic direction is less likely to be compromised or co-opted by a white establishment that finds twerking “edgy” and “cool”.

“Labels like Stormzy’s #Merky give black artists the chance to support their own and equally ensure that no one else ends up ensnared and swallowed up by the machine”

More vocal artists respond to label furore with avoidance, with some now refusing to sign altogether, instead choosing to start their own labels – Stormzy’s #Merky being one of the best known. Applying the “for us, by us” principle directly to business dealings places black wavemakers on the same level as labels and allows them to negotiate on a standpoint that refuses to accept less than what they are worth. It gives them the chance to support their own and equally ensure that no one else ends up ensnared and swallowed up by the machine.

Alexandra Ampofo, a live music booker for Metropolis Music (part of Live Nation UK) tells me that touring corporations play an equally-relevant role to that of distributors. In her experience, “labels and touring are completely separate and rarely intertwine”. As a result, most of the artists she personally works with are unsigned but equally very established.

As an increasing number of artists are making the majority of their income through live performance, there is some relief in the touring industry being more open to independent artists as a whole (though, with both coronavirus and the climate crisis, this model is set to be in flux). Steadily balancing industry participation with independence, Alexandra sees the future as one of “short-term deals and distribution”. This makes more sense – an A&R I speak to later likens distribution deals to a “friends-with-benefits-situationship”, in that it offers artists the convenience and access they desire for their music, but still allows them to maintain relative control of their work.

New artist perspectives

Unsigned and independent South London vocalist Jaz Karis confirms her current independence is equally the result of feeling “burnt out” from past management situations as much as wanting to “own my own work – that makes it even more personal for me when I share it with the world”.

“To one artist, a label is the dream that has allowed them to live the life they have always wanted and to the next it’s a contract they wished they never signed”

– Jaz Karis, artist

For her, the relationship between labels and artists is a double-edged sword, “to one artist, a label is the dream that has allowed them to live the life they have always wanted and to the next it’s a contract they wished they never signed.” While it appears easy for non-artists to condemn those who sign, there is a tougher balance to be negotiated between artists who want to own their work directly, while still partnering with the necessary short-term distribution services to finance and release projects. Although bad past experiences can leave a sour taste in one’s mouth, there’s arguably still a necessity for artists to keep their heads in the commercial game, albeit with some caution.

How to protect black talent

For Ghadir Mustafa, a scout for XL Recordings, contractual woes can be mediated by artists having an open and trusting relationship with their A&R. This extends to them understanding an artist and their intentions for their music – so sometimes that also means “not going for the shiny deal with the big advance”. Staying true to their craft is as much the responsibility of the artist as it is of the team they work with, and the integrity of this relationship should start from the very first interaction with any label, not further down the line.

As labels grow to recognise the power among black artists and consumers, Ghadir contextualises things that were entirely foreign decades ago – even a couple of years ago. “Seeing our artists chart is common practice now, and I remember a time when we would share it on our stories every time, even if we weren’t fans of the music because it was such a moment”. Black artists who’ve made their name with or without the industry have come a long way, and knowing their worth can only give them more bargaining power.

“Above all else, Megan Thee Stallion’s label controversy is one bullet point in a long list signalling a music industry in need of change”

Ghadir puts it aptly – “the money being thrown around in music right now is crazy and the artists, especially in the UK, are very much aware of it”. Predicting the future isn’t easy, but Alexandra Ampofo’s earlier warning rings true: “If someone has set out to fuck you over, then that’s what they’re going to try and do.” If an institution shows little chance of reform, then new artists must very quickly learn how to manage the beast they are confronted with. Taking your eyes off the ball is a costly mistake, but the experience gathered in negotiating and perhaps calling the bluff of big names in the industry is a gamble that can pay off.

Above all else, Megan Thee Stallion’s label controversy is one bullet point in a long list signalling a music industry in need of change. As glamorous as more black A&Rs might look for the sake of diversity changes, the structure underpinning these relations has to be re-examined. Artists too, must become active steerers of their careers and not simply passive recipients of glory. With progress, giving an inch and having a mile taken should become a thing of the past.