Author

Confronting anti-Asian racism as one of the first Chinese adoptees in the UK

Rosie’s parents were one of the first British couples to adopt a child in China, but how did growing up in a predominantly white area affect her identity?

Rosie Shead and DiyoraShadijanova

16 Apr 2021

My parents were one of the first British couples to adopt a child from China. After two attempts at IVF, it was clear that in their early 40s, they were considered too old to adopt domestically by social services. As they considered other routes to starting a family, including adopting from Europe, a throwaway comment from a speaker at an event on adoption turned their attention to China. At that time, social services were under no statutory obligation to assist with intercountry adoption and so it took three years of battling with social workers and faxing documents across the world and back before I was in their arms on the flight home in April 1995. Against the backdrop of the One Child Policy and its profound impact on child abandonment, China had only opened its doors to intercountry adoption around three years previously. When I was three, my parents adopted again from China and brought me back a little sister.

From a young age, my parents made a valiant effort to teach us about our heritage and encouraged us to take an interest in Chinese culture. My dad recently explained that this was not only to help us understand where we are from, but to show us that our Chinese heritage was nothing to be ashamed of: it was something to be acknowledged and celebrated. We were taken to Mandarin classes, Chinese New Year celebrations with other adoptees and up to London to visit Chinatown and exhibitions on Chinese art and history.

Despite this, I still felt hugely disconnected to Chinese culture. My childhood was spent watching Tracey Beaker, singing along to Spice Girls and buried in Harry Potter books. My teenage years flew by as I was glued to MSN, obsessing over my MySpace layout, and spent Friday nights drinking Smirnoff Ice and strutting around to Destiny’s Child with my friends. Living in suburban Essex, I felt culturally closer to the lives of the people I watched on The Only Way Is Essex than my birth culture. My Chinese heritage felt a million miles away.

“Living in suburban Essex, I felt culturally closer to the lives of the people I watched on The Only Way Is Essex than my birth culture”

Growing up in a predominantly white area, I was keen to dismiss as much of my Chinese identity as I could, in order to ‘fit in’. I had no real life East Asian role models and on the rare occasion I did see a face that looked like mine on TV, it would almost always be an example of the hyper-fetishised, dehumanised representations of East and South East Asian (ESEA) people that dominate Western mainstream media. It’s no wonder I internalised some of this racism.

As a child I cringed whenever I had to tell anyone my Chinese middle name. As a teenager I deleted photos where I thought my eyes looked ‘too-Asian’. At university I firmly distanced myself from the ESEA international students and the atmosphere of open hostility towards them from white students. Although I have come to embrace much more of my identity through my 20s, shadows of internalised racism remain and I still mourn the teenager who spent hours Googling makeup tutorials that could help her eyes look larger.

Despite my efforts to bury my non-white identity, racism has haunted me throughout my life. Every time someone has shouted ‘ch**k’ at me on the street, cornered me to ask ‘Where are you really from?’ or when a friend said my new boyfriend had caught ‘yellow fever’, it’s been a piercing reminder that no matter how ‘British’ I feel inside, my ‘skin-deep’ Chinese-ness means I will always be a target for xenophobia and racism.

“Every time I fill in a form and am asked to define myself, I hover between ‘Chinese’, ‘British Chinese’ and ‘Asian – other’”

When strangers hear my Essex accent this often leads to questions about my identity and an expectation that I should explain why I look and sound the way I do. I go against their preconceived ideas of what an East Asian woman ‘should’ be like and their questions show a need to interrogate and categorise people who do not fit racial stereotypes. Whether these microaggressions come from a place of malice or curiosity, the fact that these questions are so common reveals the sinister societal attitudes towards people of colour and the persisting notion that we will never truly ‘belong’ in Britain.

In the past I’ve felt conflicted speaking about racism I’ve faced: weighed down by guilt for rejecting my heritage as a child and the acknowledgement that I’ve been shielded somewhat from discrimination by my parent’s privileged backgrounds. I attended a private primary school, went onto grammar school, university and achieved my Masters with my parents’ financial support. I’m also acutely aware that I do not share in the experiences of immigrant families who are so often marginalised within society.

Even now, every time I fill in a form and am asked to define myself, I hover between ‘Chinese’, ‘British Chinese’ and ‘Asian – other’. To me, these rigid tick boxes symbolise the rudimentary understandings of race in the UK and the continuing conflation of ethnicity, race and cultural background. It’s clear these options are nowhere near nuanced enough to capture the full complexity of people’s identities or the hugely diverse stories of human migration. I am all of the above, while feeling none of the above. The dichotomy of my identity, how others interpret my Chinese face and how Westernised I feel inside may always feel mismatched.

“While I’m still unpacking the complexities of my identity, I feel more ready than ever to embrace all parts of me”

With the dramatic rise in anti-Asian racism, I feel a tinge of fear every time I leave the house. Although anti-Asian racism, including the lack of representation, white-washing and fetishisation of ESEA people has always existed in our society the rise in violent hostility towards people who look like me has been alarming to watch. During my daily walks, I am twice as alert as usual: as a woman still reeling from the murder of Sarah Everard and as part of a minority group afraid of increasing racist abuse. There is a great sadness in that, despite the immeasurable diversity within the ESEA diaspora, the hatred towards us is one thing we all hold in common. Following the shooting of six women of Asian descent in Atlanta, I found myself scared and searching for permission to grieve the deaths of these women. If I have never felt ‘truly Asian’ and alienated from my Chinese side, was I allowed to share in the grief of the ESEA community?

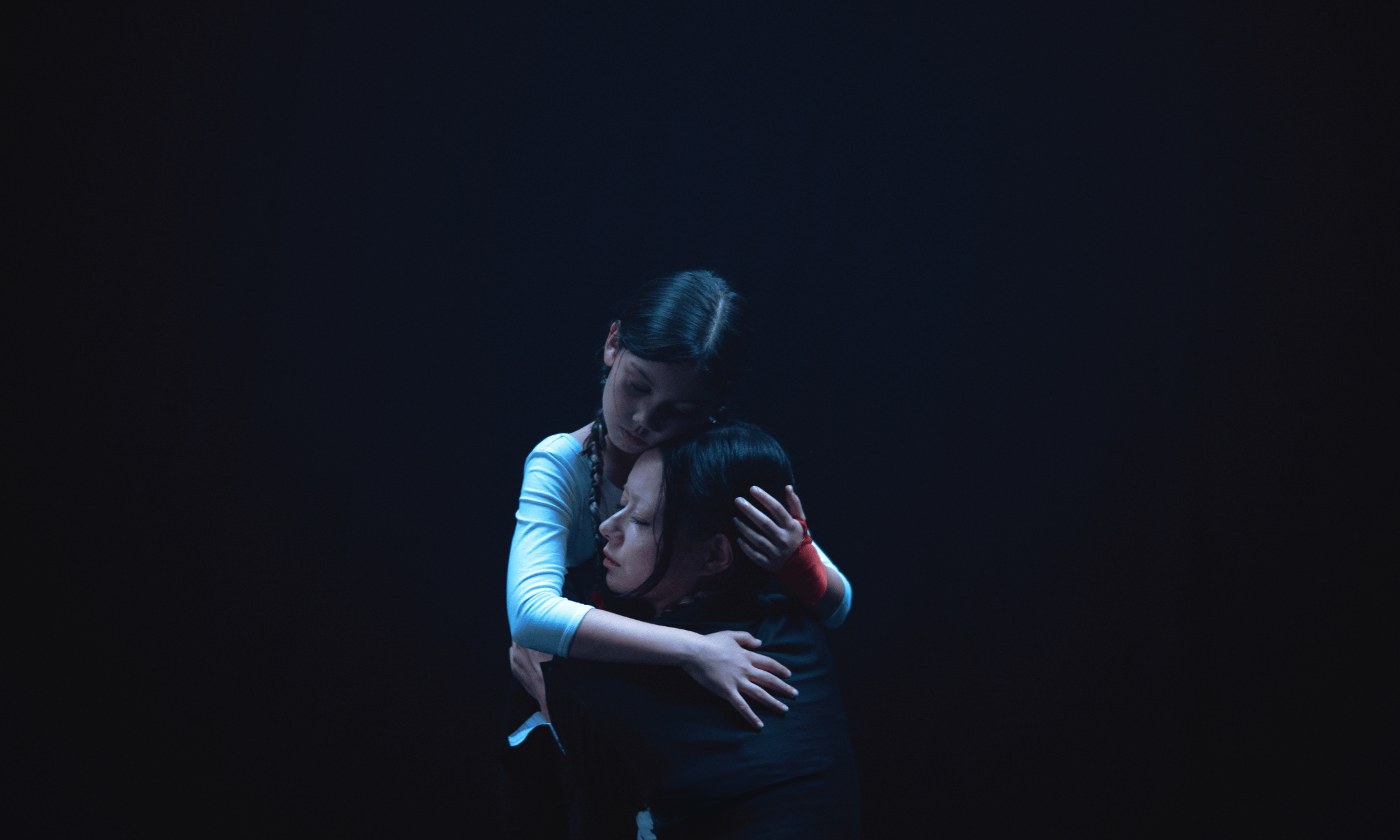

In my confusion and sadness, I reached out to other Asian adoptees my sister and I were introduced to as children. Although we hadn’t spoken much since we were teenagers, they expressed similar feelings of fear of increased violence towards people who look like us, grief for the victims of this hate and confusion around where adoptees ‘fit in’ to dialogues around race and identity.

These conversations opened my eyes to the importance of community and solidarity when facing a common threat. A space where I felt seen, understood and validated in the confusion I was feeling. Although I will always straddle different aspects of my identity and may never truly feel part of the British Chinese population, I belong to a smaller community of adoptees with whom I will always share this unique connection.

The last year has reminded me that no matter how I identify, I will always be racialised by others for the rest of my life. I’m both Asian ‘enough’ and British ‘enough’ and I don’t have to adopt a certain culture to have a voice. While I’m still unpacking the complexities of my identity, I feel more ready than ever to embrace all parts of me and to continue to speak out in solidarity against anti-Asian racism.