Extinction Rebellion need to focus on the fact that climate displacement will largely impact communities of colour

Sharlene Gandhi

11 Oct 2019

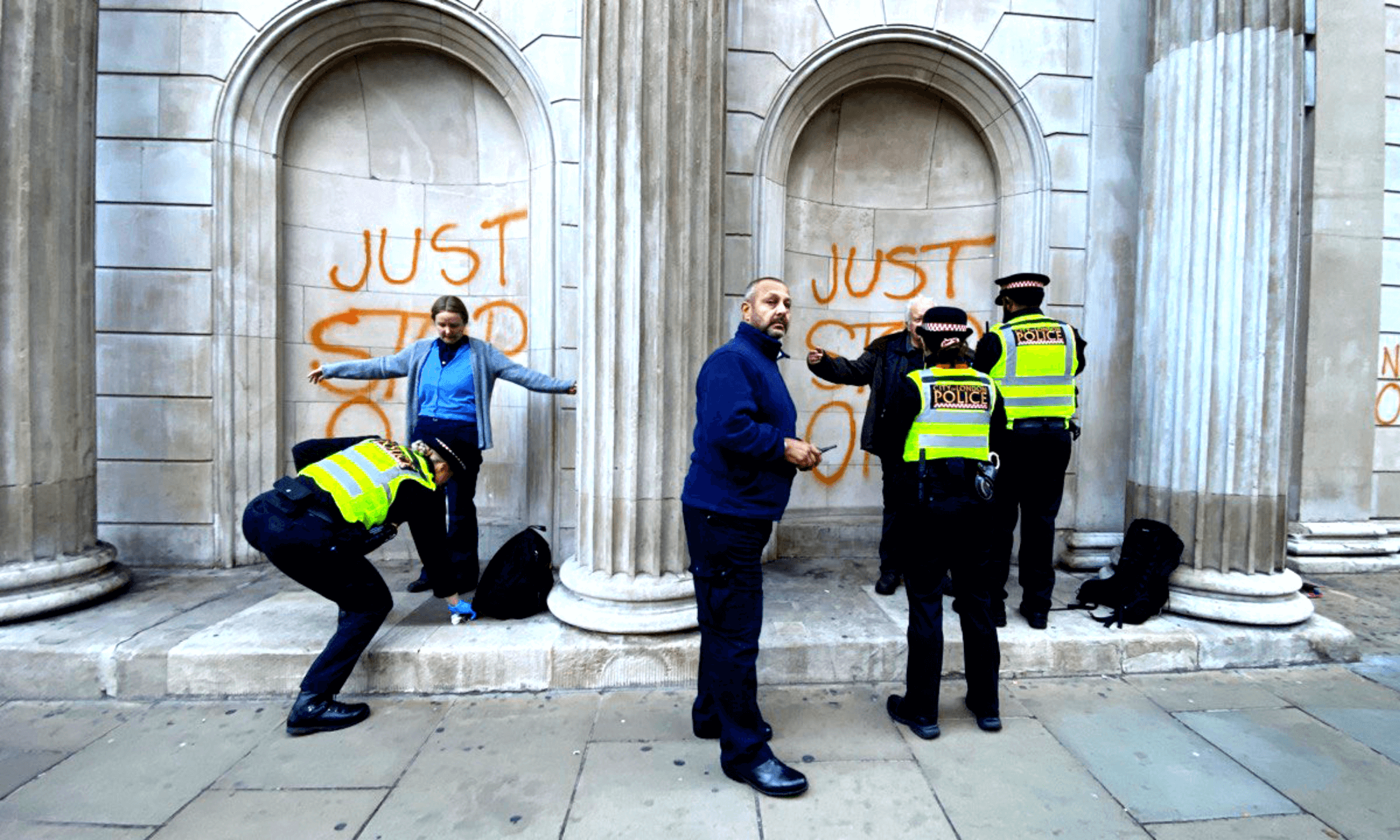

Photography by Akil Mazumder

Extinction Rebellion are out in full force again. The brand of the protests of summer 2019 were the colossal, road-blocking pink boats, stationed at major junctions and marked with bold words: “Tell the truth.” This time round it’s the hundreds of tents pitched up in and around Westminster, with a bold, unwritten message: We’re not going anywhere. Between both sets of protests, however, there is a consistency: the overwhelmingly white crowds, some of whom are now martyring themselves to police arrest, and others, like XR spokesperson Rupert Read blaming “large-scale immigration” as a cause of “dangerous climate change.”

Extinction Rebellion is future-focused; those getting arrested are telling the police that they are “doing this for their [the police force’s’] children” too. But treating climate change as a future problem invalidates the experiences of those living with the impacts of climate change as a now-problem. And, communities of colour are the vast majority of those bearing the brunt of climate unpredictability as we speak.

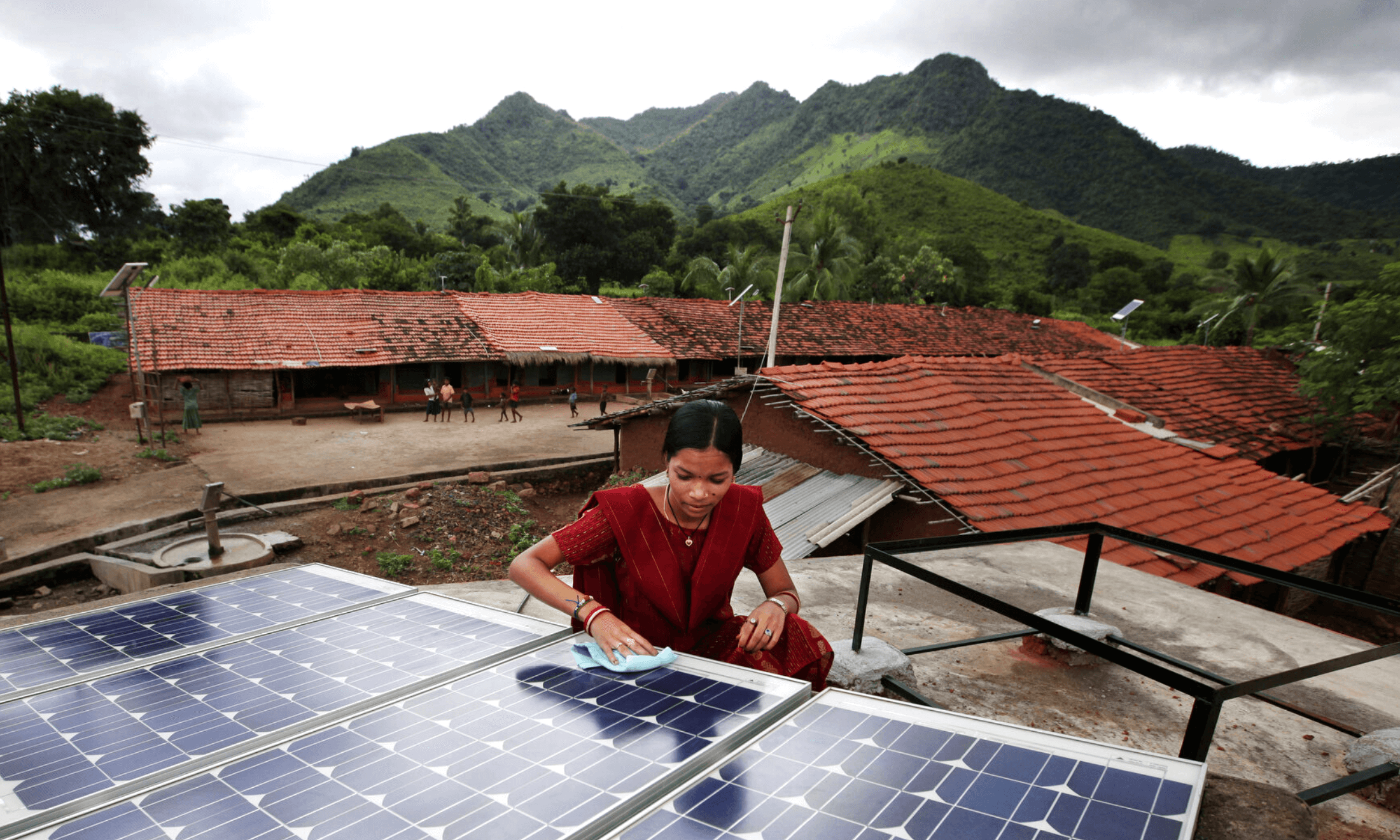

Communities of colour in the Global South are experiencing ever-warmer climates that will continue to heat up as global temperatures rise – India and Pakistan reached a record-breaking 51 degrees Celsius in 2018. China and India have been identified by economists as being the most prone to collapse; cities such as Beijing and Kolkata are already recording unlivable levels of smog pollution, due to ever-increasing demand from mostly Western economies for cheap goods. As collective consciousness of our environmental impact increases, these trade practices are likely to evolve into something even more nefarious: what sociologist Doreen Martinez has labelled “climate colonialism”. For example, energy derived from solar panels in Morocco could end up being rerouted to Europe, at the expense of local prosperity.

“Treating climate change as a future problem invalidates the experiences of those living with the impacts of climate change as a now-problem”

“Think of some of the largest cities in the world and where they are,” says Asad Rehman, Executive Director of War on Want, “Rio, Mumbai, Hong Kong and Shanghai – to realise what sea level rises will mean.” Not only will coastal erosion naturally wear these densely packed, urban communities away, but locals will be living in increasingly precarious conditions, a strain that can have dire impacts on bodily and mental health. It is difficult to put a tangible figure on economic loss after a climate disaster due to the widespread impacts of loss of life, community and business. However, the fact that just one tropical storm that hit Dominica in 2015 pushed back “development” gains by approximately 20 years gives us an indication of the severe battering these communities are facing.

But communities of the Global South have not been silent. In South America, citizens have taken to the streets in Brazil and Bolivia to protest water restrictions – the retraction of a fundamental human right for private interests. The famous Chipko Movement – meaning “Stick to it” – in India was a 1970s eco-feminist movement which saw women in rural areas literally embracing trees to prevent their destruction. These communities are acutely aware of their relationship to the land and its resources, many relying on it to feed themselves and participate in the global food trade. But these economies often do not have the resources to rebuild broken communities, and they often live in politically fraught contexts where their protests are rarely taken into consideration. This slow pace of change, combined with increased precariousness, compels people to move from spaces that they call home in order to feel safe and secure.

Meanwhile, in the Global North, communities of colour are also arguably in crisis. In the UK, people of colour are clustered in major cities such as London, Manchester and Leeds, all of which have recorded some of the worst smog levels in the country. Smaller communities of colour have formed in factory towns: Blackburn’s minority population is at 31% and Burnley’s stands at 12% in comparison to the Lancashire average of 8%, and Derby has a sizeable Pakistani community. Living in a factory town exposes communities to gas emissions which have significant health impacts. In my ward of Edmonton, North London, a community that is 80% made up of people of colour, a new waste incinerator is in the works, alongside talk of clearing nature reserves for a new landfill site.

In the United States, four of the states facing a water crisis are also home to the highest proportion of minority populations: California, New Mexico, Nevada and Texas. The US government has been deeply criticised for a lack of response to Hurricane Katrina, a tragedy which struck in 2005, disproportionately impacting and now continuing to haunt the black community. Clare Morganelli of the Climate and Clean Energy Programme notes how the housing market in Miami has become a case-study for “climate gentrification”; properties at higher elevations have risen in value, thus phasing out low-income, often minority, communities.

A striking example of environmental racism in the US is the Love Canal tragedy, in which a New York neighbourhood, largely home to low-income and minority populations, became a dumping ground for Hooker Chemical Company. The fumes emitted by the waste were causing abnormal births and miscarriages. Speaking to Dr Elizabeth Blum, a professor who studied the Love Canal disaster, highlights the importance of seeing climate change as an “intersectional issue”: “[Love Canal] reveals a lot about race, class and gender,” she says. Similar to the Miami housing market, when landfill sites become part of a local area, the land value decreases, she tells me.

“The single-minded focus on the technicalities of climate change ignores the capitalist and racist tendencies that have led global warming to become the disaster it has”

Research suggests that there is an action-concern gap in communities of colour when it comes to climate change. Adam R Pearson reported, in a 2017 paper on climate change communication, that people of colour were “least equipped to respond to climate change”. These academics came to the conclusion that part of the issue was “minorities’ [lack of] environmental engagement, which may be particularly salient among historically disenfranchised groups and immigrant groups who have emigrated from regions with high levels of government corruption”.

However, when communities of colour have tried to exercise their right to protest, they have been met with unspeakable forms of backlash. Natasha Josette reported that in a 2015 climate march led by decolonial climate justice group Wretched of the Earth, was hijacked by a group of people in animal headgear attempting to make the group’s message appear more palatable and positive. Police officers and associated brutality have been deployed whenever Indigenous communities have protested pipelines or drilling in the USA and Canada. If communities of colour are told implicitly that their political voices, and their lives, do not matter in comparison to their white counterparts, it becomes futile for them to spend time and resources protesting.

Not only are communities of colour in the West unable to push for environmental policy change in their hometowns, but they are also tied to these increasingly unsafe areas, often for economic reasons: employment is easy to find in manufacturing towns or urban areas. More horrifyingly, migrants and low-wage workers are often found in pollutant, dangerous professions. Eric Schlosser reveals how the American meatpacking industry is essentially run by Latinx immigrants in his book Fast Food Nation. This community then suffers the dire health implications of working in such an environment. For these people, voluntary migration is a distant dream.

Extinction Rebellion are enthralled by the science of the climate crisis, which is an undeniable piece of the puzzle. However, the single-minded focus on the technicalities of climate change ignores the capitalist and racist tendencies that have led global warming to become the disaster it has become today. As Wretched of the Earth writes, “When you focus on the science… you look past our histories of struggle, dignity, victory and resilience… In order to survive, communities in the Global South continue to lead the visioning and building of new worlds free of the violence of capitalism”.

Britain is one of the biggest contributors to global warming; its historic use of coal has contributed hugely to the many ozone holes hanging over other nations today. The UN has taken this “historical responsibility” into consideration to ensure equitable negotiations, but Britain must take a more active role in supporting those who are now facing the consequences of its historic greed.

Britain must learn to build mutually beneficial, sustainable partnerships with other nations. It must provide homes for those who have lost them, and deal with the social fragmentation that will inevitably arise from it. It must acknowledge the arbitrary nature of its borders, recognising that everybody and everything is at the mercy of climate change.