Why are so few people of colour being referred for eating disorder treatment?

Nadia Craddock

14 Mar 2019

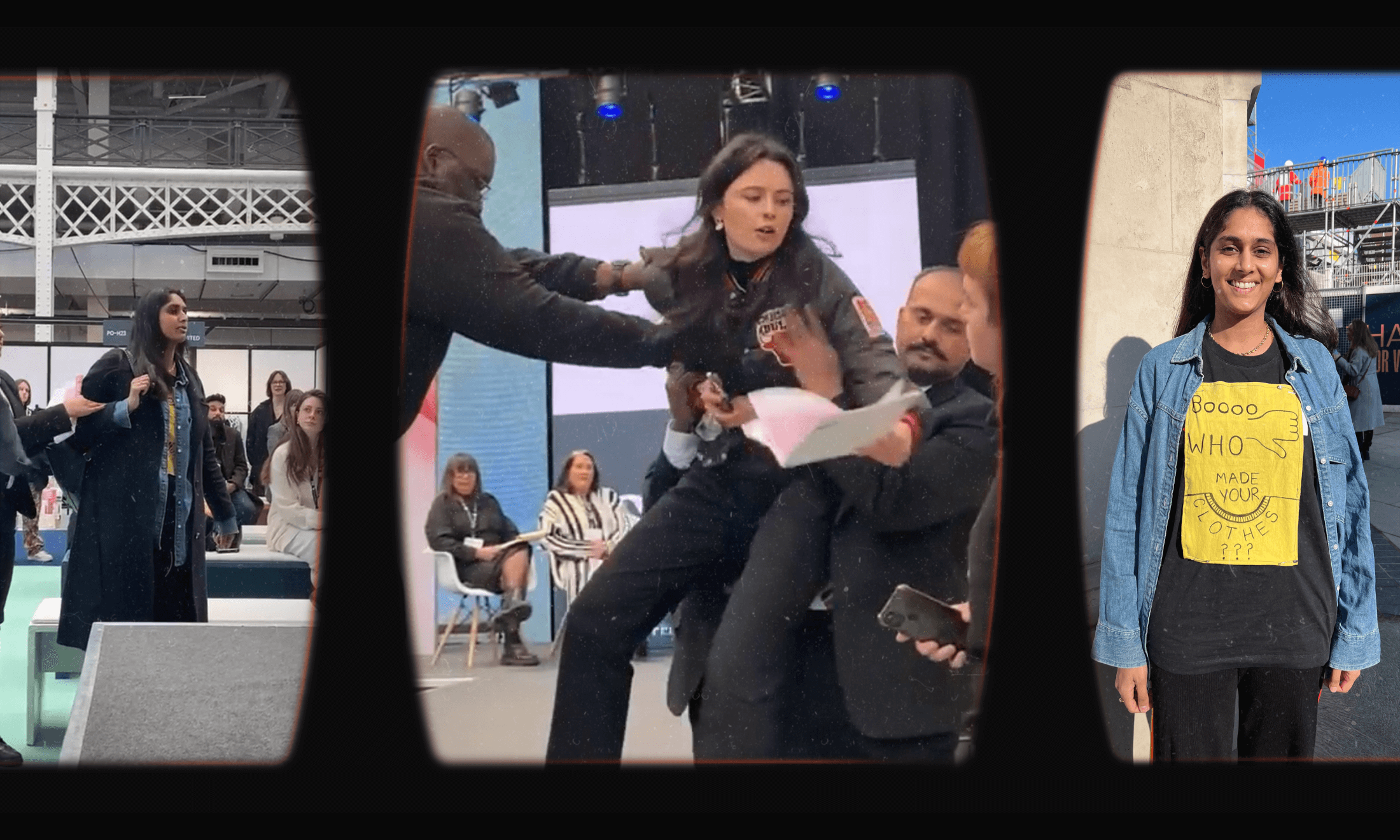

image by Kristin De Soto

TW: Explicit mentions of eating disorders throughout

25 February – 3 March was Eating Disorder Awareness Week. This year has been the first year I’ve dipped my toe into the conversation and shared snippets of my story on social media. Despite anorexia being a constant feature throughout my teens and 20s, I’ve never felt particularly included or represented in conversations around eating disorders. As a result, I have always distanced myself from it, occasionally watching from the sidelines. But this year, the theme set by the UK eating disorder charity BEAT was Break The Barriers and there was a big focus on *diversity*. For the first time it felt like people wanted to hear my story, which made me really think about whether I even wanted to share my story, and if so how, and where would I begin?

The conflict surrounding sharing my story is complicated by the fact that my work as a (baby) body image researcher includes work on eating disorders, specifically eating disorder prevention. This makes things weird because one, there is still

“Those who did not meet the thin, white, middle-class, young woman stereotype were less likely to self-perceive a need for treatment”

But then, I also know from the research that stereotypes seriously impede seeking help for and receiving eating disorder treatment. For example, a recent study published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders found that among a group of 1700 young people with eating disorder symptoms, those who did not meet the thin, white, middle-class, young woman stereotype were less likely to self-perceive a need for treatment and were less likely to have received a diagnosis or treatment in the past 12 months.

Other studies help to unpack some of these disparities. For example, a common barrier for men when it comes to seeking help for eating disorders is tied up in toxic masculinity and the idea that eating disorders are a women’s issue. Specialists focusing on men with eating disorders also highlight that many of the tools for eating disorder diagnosis have been designed with female presentations of eating disorders in mind and thus men with eating disorders can fall through the net because their symptom profile can differ significantly. On the subject of gender, research suggests that transgender people are at greater risk of disordered eating than their cis-gender peers, yet there is very little research examining how to best support and meet the needs of transgender people with eating disorders.

“Studies found that the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms is comparable across ethnic groups, fewer individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds are referred for eating disorder treatment.”

People of higher weight are also less likely to receive a diagnosis or treatment. Significantly, research indicates eating disorder professionals are not immune to weight bias and holding negative attitudes about people who are larger in size, which undoubtedly has ramifications for treatment and care. Personal accounts suggest that despite reporting eating disorder symptoms, people of higher weight are still encouraged to diet, even though it is well established that dieting is an important risk factor for disordered eating across the weight spectrum, as well as future weight gain. Being told to diet will likely serve to exacerbate a person’s eating disorder, making this advice unethical. Yet, it’s widely accepted thanks to society’s fat-shaming culture.

While recent studies found that the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms is comparable across ethnic groups, fewer individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds are referred for eating disorder treatment. Cultural differences could play a significant role in seeking help (e.g. mental health stigma) as well as biases, preconceptions, and a lack of cultural sensitivity from healthcare professionals. It’s perhaps worth mentioning here that eating disorder professionals are predominantly white, middle-class, slim women.

“I was never denied treatment. I now recognise this is a privilege. But being brown factored into my eating disorder in other ways”

Considering the research compounded with the evidence that indicates that fewer than 30% of people with eating disorders receive professional help, and the knowledge that eating disorders are serious, complex, costly, life-threatening illnesses, there is a compelling argument for breaking down barriers. If awareness through personal narrative can encourage people to seek treatment and provide insight to providers, then perhaps, on balance, it is worth sharing snippets of my story. What’s more, evidence suggests that early intervention plays a huge role in the success rates of eating disorder treatment.

So where to begin? I was diagnosed with anorexia at 16 and I was last in treatment at 28. At 33, I am “well” in a way that I could have never imagined during that 12 year period. Not just in terms of weight and food, as eating disorders are not truly about either, but acknowledging a freedom around food that I have not known since I was around 13 – a full 20 years ago – is a good marker for me.

“I was often told I was “lucky” because I was Asian and thus “tiny” like my mum. I wanted to capitalise on that luck”

Reflecting on some of the disparities in treatment, being brown (I’m mixed race) was never a barrier to treatment *for me*. My weight was always low enough to cause alarm; I was never denied treatment. I now recognise this is a privilege. But being brown factored into my eating disorder in other ways.

Like most kids, I wanted to fit in and was often conscious of being one of the few brown kids. I wanted to distract from the fact I was brown and often wearing second-hand clothes by being the kind of thin that was fashionable at the time. Being thin made me cool; it was my access point to coolness.

I was often told I was “lucky” because I was Asian and thus “tiny” like my mum. I wanted to capitalise on that luck. It took me a long time to come to terms with the fact that I don’t have my mum’s build. I have my white father’s build. Also, Asian is not a body type. There was the pressure to work twice as hard for half as much, a pressure I feel has only grown since leaving school. There was the everyday racism and microaggressions that come with being “funny tinged” (I’m still not over that expression) and the pressure to be the most palatable kind of Asian in a white world.

It feels so weird to tell this story. I get embarrassed by the fact that I was unwell for so long and that I still struggle with periods of crippling anxiety and low confidence in a way that even I find annoying. But there is a purpose to my work and the more I grow my community, and the more I use my voice, the more courage I have and the more distant my eating disorder story really becomes.