How the legacy of Hong Kong’s Bleak House Books will live on

Poet Tammy Lai-Ming Ho pays tribute to the bookshop, which closed on 15 October, and all that it meant for Hong Kong.

Tammy Lai-Ming Ho

15 Oct 2021

Jessie Lau

“I’m home again!” That’s how I would feel every time I walked into Bleak House Books (BHB), the much-loved independent English bookshop which opened in San Po Kong, Kowloon, a former industrial district of Hong Kong in 2017. No other bookshop in the city or elsewhere gave me this sense of elation and content when I stepped foot in it. BHB was special like that: it was welcoming, made you feel comfortable and that you belonged, and it also gave you licence to be part of its world.

Between 2018 to 2021, I moderated a number of readings at BHB, on a range of topics: poetry, world literature, translation, politics, freedom, Cantonese, love, Hong Kong, and more. Some of these events, such as ‘Matches Polished into Lights: Tiananmen Thirty Years On’, packed out the entire shop. Looking at photographs from these nights bring back memories; I see myself now standing in front of the bookshelves, inimitably decorated with lovingly hand-written signs. I stand with different speakers – many of whom made multiple appearances in the shop – and am sometimes joined by Albert Wan, BHB’s co-owner. Although the people attending are the focus of these images, the books on the shelves are never merely background props.

BHB officially closed on 15 October. It was the best kind of bookshop. The titles it carried were wide-ranging, unpredictable, delightful, uncompromising, and you always left with your bag heavier and your mind more curious, eager to get home and read the books you had just bought, often ones you had discovered for the first time (a particular hallmark of BHB). The shop’s selection was at once personal and communal. During a historic period for Hong Kong, marked by mass protests and the gradual erosion of our freedoms, BHB was one of the few remaining places where you could get hold of what some would consider politically sensitive books.

Buffeted by social unrest, political crackdowns, Covid-19, and in its last week, two days of Typhoon No. 8, BHB did business at a particularly difficult time in Hong Kong. And yet something miraculous happened — it was a vortex that drew people in, again and again. Though it was very much a neighbourhood shop, for many people, going there involved a bit of a commute. A person would have had to make a conscious choice of heading to San Po Kong and taking the lift all the way up to the 27th floor, where they’d push open the glass door and be welcomed by a little shrine of notices promoting local events and activities, before their eyes rested on the carefully curated books.

“During a historic period for Hong Kong, marked by mass protests and the gradual erosion of our freedoms, Bleak House Books was one of the few remaining places where you could get hold of what some would consider politically sensitive books”

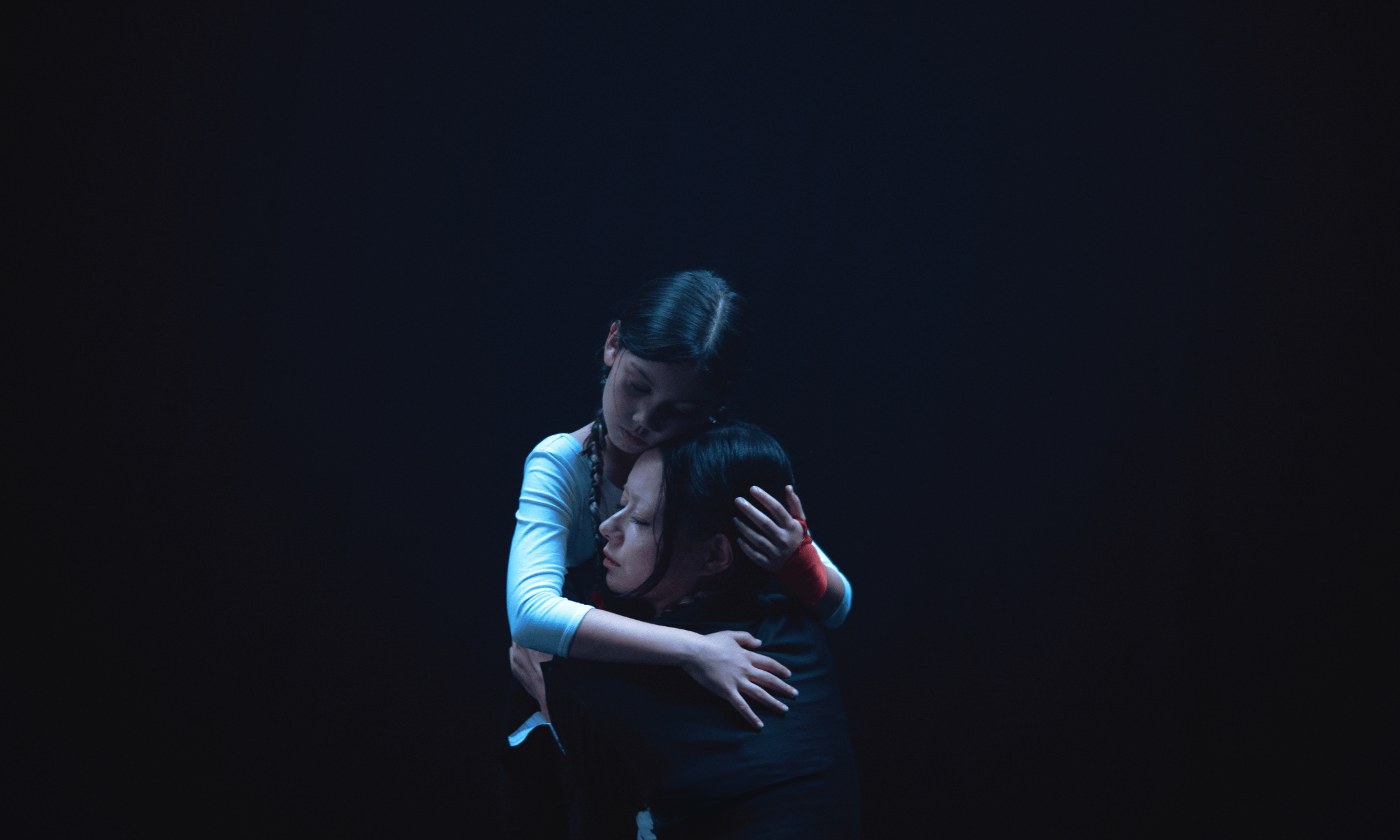

One day, out of the blue, Albert wrote to me, telling me he was going to close the shop. I was deeply saddened but I wasn’t shocked. I did feel relieved, however, that he and his wife (also the shop’s co-owner) Jenny had made the decision to up sticks and leave Hong Kong with their children. The city has changed substantially over the past few years — sadly, for the worse. Shortly afterwards, Albert announced the closing to BHB’s customers in a blog post entitled ‘The Last Memo’: “Given the state of politics in Hong Kong, Jenny and I can no longer see a life for ourselves and our children in this city, at least in the near future.”

BHB did not only do ‘business’. It brought people together — readers of different ages and backgrounds — in one place. It created its own unique community anchored by the BHB ethos: a love of books and reading, good citizenship, and a passion for Hong Kong. A bookshop. A meeting hub. A classroom. A venue for lively readings and discussions. A recording studio. A darkened space for the occasional film screening. A place for life events: a place where a customer once proposed marriage, where books were launched, where friends and students bade farewell to a poet who had lived in Hong Kong for a long time.

“BHB did not only do ‘business’. It brought people together — readers of different ages and backgrounds — in one place”

As is the case with many bookshops nowadays, BHB was social media–savvy. The space was finite and constant but the people it attracted varied—and it was this mix that made the bookshop’s feeds so interesting, for we witnessed a living, evolving being. There might sometimes be pictures of Albert and Jenny’s children on Facebook and Instagram, themselves avid readers at a young age. Friends and followers of the shop knew that BHB was more than just a business, but a family.

In 2019, I invited Albert to speak at the first Hong Kong Studies symposium at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), on ‘The Neighbourhood’. He agreed to do it right away. In his talk, he told us about the origin of BHB, the history of San Po Kong as home to “one of the biggest movie theatres in Hong Kong”, and his vision and philosophy for the bookshop. He also revealed he had an uneasy feeling politics might come to shape the shop’s destiny.

The previous year, BHB had hosted the reading ‘Liu Xiaobo Elegies’, dedicated to the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Chinese writer, which I organised on behalf of Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and PEN Hong Kong. Like many other events at the shop, it was a memorable one that packed the place out. It was only during Albert’s CUHK talk, a year later, that I learnt some people had told him they thought it risky and dangerous to host the reading.

“Friends and followers of the shop knew that BHB was more than just a business, but a family”

Earlier this year, I was sitting with my husband on the terrace of a restaurant on Lamma, one of Hong Kong’s outlying islands. A young woman approached me with her boyfriend, holding a copy of my first poetry collection, Hula Hooping. She said she lived nearby and, upon seeing us, had gone home to get it. She asked me to sign the book. It was especially thrilling to find, from the letters “BHB” and a catalogue number neatly inscribed on the top corner of the book’s flyleaf, that her copy had been bought in the shop.

The encounter was a testament to BHB’s unwavering support of local publishers and writers, myself included. It also showed that its customers did indeed come from all over the city. I like to think that these three pencilled letters will remain for years to come on the shelves of countless Hong Kong homes — or in future homes outside of Hong Kong — and the volumes bearing them will continue to inspire their owners or find new readers.

BHB’s closure comes after the University of Hong Kong ordered that the Pillar of Shame sculpture, erected to remember the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, be removed from the campus by Wednesday, 13 October 2021. In Hong Kong’s new cold climate for dissent, it is inevitable that any memorials or symbols of the massacre or organisations that have had anything to do with its remembrance will be eradicated and outlawed. It feels like several lifetimes ago since BHB hosted that Tiananmen memorial reading in 2019.

There’s an image of Bleak House Books—mournful, serene, and somehow haunting—that I particularly like: the blinds are drawn, the lamps overhanging the bookshelves are turned off, sitting in front of the window is an empty chair, next to it is a floor lamp radiating a determined halo of light. In Albert’s translation of a line from Wong Kar-wai’s 2013 film The Grandmaster: “With one breath / the lamp is lit // Always remember // Where there is light / there is hope.”

How reconnecting with my Vietnamese heritage led me to write a novel

This Lunar New Year, Asian communities deserve the right to grieve and fear

When will fashion brands stop sexualising the cheongsam?