Inequity, performativity and white ‘provocateurs’: what it’s like being Black in alternative music spaces

With a cultural history that sees anti-racism and fascism live side by side, what are the realities for Black people in alternative music?

Michelle Kambasha

06 Feb 2021

Canva composite of press photos / Creative Commons photos

As part of the alternative music industry, I’m lucky to have peers that are mostly left-leaning and opposed to racism. Whether they’re musicians, marketeers or A&Rs we have an us and them attitude towards fascism and all of its tenets.

But one month ago, in the first week of 2021, I was reminded of a more complicated reality. On 6 January, mostly white right-wing extremists stormed the US Capitol Hill. As we watched from our social media feeds, we saw a lot of them: the anti-Black Lives Matter folks, the QAnon conspirators and the Proud Boys who were “standing back and standing by” at the request of President Trump. But we didn’t expect to see one of us.

Zooming into grainy photos, it’s clear that Ariel Pink and John Maus – moderately successful musicians with cult followings – were amongst them too.

“Only white people find being a provocateur edgy”

Shamir Bailey (musician)

Some felt disbelief, others felt it premature to condemn them. Citing their deliberately provocative alter-egos, they’d often played egregious and contumacious characters – perhaps this was just another instance of this.

But from scrappy pro-Trump tweets on Ariel Pink’s Twitter to a shambolic interview in December 2020 during which he appeared frantic, sweaty and wide-eyed, like an archetypal conspiracy theorist, it only took a little digging to see that, Ariel Pink in particular, was a fervent Trump supporter.

“Ariel Pink has been playing [his right-wing politics] in our faces for years!”, says alt-pop musician Shamir Bailey. “It’s ridiculous that it’s had to come to this.” Indeed, given past comments like “it isn’t illegal to be racist” and “I hate all that gay marriage shit”, it seems a little bit naïve to believe the impossibility of Ariel Pink being at Capitol Hill.

Nonetheless, Pink’s clear support of white supremacy has implications for Black people, like me, that enter the majority white alternative music industry space.

Anti-racism and rock music

The global rock scene has a long history of being actively anti-racist. In 1976 a movement called Rock Against Racism was founded in the wake of Eric Clapton’s infamous racist outburst in which he implored Britain to get “the foreigners out, the wogs out, the coons out” before the Isles became a “black colony”. In the 80s, American punk bands like Bad Brains and Black Flag fought to take back their scene from American national socialists who had started penetrating it.

Journalist Joshua Surtees, who is mixed race, speaks of the early 90s in the UK, where “anti-racism was overtly prominent within the scene and in music journalism”. In 1993 the murder of Stephen Lawrence lit a fire in Joshua and his peers (“there was a sense that enough was enough”) and his gig-going habits reflected this too. That same year he went to his first gig ever, Rage Against the Machine, which was an Anti-Nazi League benefit concert. In 1994, he’d march with the ANL to Brockwell Park where bands like the Manic Street Preachers played to celebrate the defeat of the racist British National Party.

“White complacency to racism in times of relative stability allows white provocateur artists the benefit of the doubt, in turn slowly pushing minorities out”

Organisations like Love Music Hate Racism, United Against Fascism and Stand Up to Racism have continued the legacy of the ANL; last year, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the re-emergence of Black Lives Matter – many white indie artists opened their pockets in solidarity. Some hosted virtual benefit concerts with proceeds going to families of Black victims of brutality, imprisoned protestors.

While all the help is greatly welcomed in times of Black trauma, what about in times of relative stability? Black people still continue to face racism in its more clandestine forms, and this is typically when white complacency sets in, allowing a hostile environment to grow, affording white provocateur artists the benefit of the doubt when they hint at the macabre, in turn, slowly pushing minorities out.

Flirtations with fascism

Rock music’s flirtation with fascist imagery is as long as its commitment to anti-racism. People talk about Morrissey like he’s a bad egg, not symptomatic of a wider problem. From Siouxsie Sioux photographed with a swastika on her arm, to David Bowie’s proclaiming to Playboy our need for a fascist Prime Minister, it’s usually just chalked up to being just harmless shock value. More recently, Danish punk band Iceage were accused of promoting racism with fans noting Klansmen-like characters in their music videos, even suggesting national socialist bands to check out in interviews. “Taking interest in the depraved isn’t a bad thing,” the lead singer told the Guardian – this is true, but platforming these ideas publically is very different and very dangerous.

“People talk about Morrissey like he’s a bad egg, not symptomatic of a wider problem”

At best, it alienates Black fans. “Only white people find this edgy,” Shamir says. But it also puts Black people in harm’s way, he adds: “These comments and symbols aren’t accidental, they’re to ensure the continued whiteness of that space, and of the culture.”

It’s telling, then, that as the circus around Pink’s attendance of the rally unfolded, the only outlets that would platform him were right-wing white spaces, like the Trump-sympathising, Murdoch-owned Fox News channel (it’s estimated around 9 in 10 of its viewers identify as white).

Whitewashing and betrayal

“The music industry is so powerful in how it perpetuates a white image in alternative music”, says Nilüfer Yanya, a 25-year-old mixed race alt-musician, who grew up thinking that “alternative music = white.”

Black artists who veer towards alternative music like FKA Twigs and even genreless music like Moses Sumney, will still be boxed in as R&B artists.

Peer-led initiatives like buying Black on Bandcamp encourage fans to break away from this perception, paying Black artists directly and discovering the variety of music that Black people from all over the world create that isn’t often pushed. As Stephanie Phillips, from Black feminist punk band Big Joanie says “It’s hard to remind people that it’s our genre too and you’ll work a lot harder to gain recognition… [but the] internet has democratised certain genres and music.” She says that, by using DIY tools like Bandcamp, “you can still find your people”.

“The music industry is so powerful in how it perpetuates a white image in alternative music”

Nilüfer Yanya (musician)

But Black music is the blueprint for most modern popular music. Melanie McClain, who works as a publishing A&R at leading independent label Secretly Group, has noticed that “white musicians like to work with what they perceive as ‘Black’ sounding things […] being Black adjacent is cool.” There are lasting implications when music is taken, borrowed, stolen and whitewashed. Cautionary tales of musicians not being credited or remunerated are plentiful. Because Black music stems from pain inflicted by oppression, it makes the music inherently political; whitewashing the music is, therefore, political in itself. “We have to be cautious”, says Melanie, “because they might betray us.”

This betrayal takes many forms. It could be purporting to be left-wing but not being actively anti-racist.

Shamir cites the ‘Yes We Can’ Obama administration as an example. “There was a lot of unrest for Black people during that administration, but a lot of people passed on it, because of what Obama represented.”

Meanwhile in the UK, after years of a Conservative government, Tony Blair’s New Labour felt like real hope, promising unity. “It became ‘right, we have a left-wing government now and everything is being addressed,” says singer and actress Lisa Moorish, who was a key figure in the Brit-Pop ‘Cool Britannia’ scene of the 90s, “But of course it wasn’t.”

Joshua says Oasis and other bands in that scene could have done more to denounce racism, citing Billy Bragg as an example of someone who demonstrated pride in the English cultural heritage, while also being vehemently anti-racist. It is possible.

“People like John Lydon and Ariel Pink made their careers and success off the back of left-wing liberals”

Joshua Surtees (journalist)

The wound is deeper when the artists themselves do a U-turn in their politics. In recent years, John Lydon’s supposedly left-wing anarchism has been brought into question. It’s perhaps the greatest example that left-wing philosophies aren’t sufficient in combating racism. The Sex Pistol was accused of viciously attacking one of the few prominent Black figures in the modern alternative scene, Kele Okereke of Bloc Party, and shouted “‘the problem with you is your black attitude.” Okereke said at the time, “I am disappointed that someone I held with such high regard turns out to be such a bigot.”

Joshua understands why fans – even white fans – would feel betrayed by artists like John Lydon and Ariel Pink. “These people made their careers and success off the back of left-wing liberals…to turn around once they’re successful and reveal themselves to be right wing and, at best, indifferent to racial causes, is like spitting in people’s faces.”

The ramifications of inequity

Betrayal could even be white artists failing to recognise their (often middle-class) privilege. The irony isn’t lost on me that Ariel Pink is the son of a defamed multi-millionaire, a wealth he was once heir to. The industry is built on the backs of poor and disenfranchised Black people, yet we let people like Pink, from 1% kind of wealth be the voices of the scene.

Laeticia Tamko, the artist behind Vagabon, speaks of the “so-called punks” that she’s come across who “judge musicians that want to be paid”. Meanwhile, “they have a back-up plan, a house in Connecticut they’ll inherit from their parents, yet they’re the judge and the jury.” Speaking on how Ariel Pink has finally been exposed for who he truly is, Laeticia adds, “a costume will always be just that.”

All of this is mentally taxing for Black people. The inequities in the scene have been obvious to us, but our white counterparts are just catching up. Because we’re in different stages of awareness, our ability to understand each other can be fractured.

“In order to continue loving what I do, I have created a little bubble where I can

distance myself from the harsh realities”

Laeticia Tamko (Vagabon)

“If I had a pound for every white middle class woman in music that said to me ‘you’re so angry’ because I’d voiced my concerns about racism…” says Lisa of the relentless gaslighting she has experienced. Then there’s bearing the weight of white guilt: “I have to be honest, that it was easier processing the murders of Black people and Black Lives Matter in quarantine,” says Shamir, “because I didn’t have to deal with guilty white people – the guilt is self-serving anyway.”

When I ask how Laeticia has been affected, she answers hesitantly, “I’m more interesting than the pain I’ve endured. [But] I’ve become much of a recluse. In order to continue loving what I do, I have created a little bubble. One where I can distance myself from the harsh realities. Who knows if that’s healthy but it’s how I cope.”

Decolonise Fest and the future

Stephanie has chosen a proactive route. She and her Black and brown friends were minorities in the London punk scene when she first entered it 10 years ago. But as the first incarnation of Black Lives Matter in 2014 gained traction, they started to mobilise, asking themselves, “do we want to sit around and accommodate whiteness all our lives?” So she started her all-Black, all-women punk band and created Decolonise Fest, a safe-space for Black and brown people in the punk scene to gather. The punk ethos is also helmed, but crucially through the lens’ of Black and brown people, which means committing to monetary investment without judgement from some of their white privileged punk peers.

Choosing to remain in the industry is a brave and often difficult choice. Being one of few Black people at a gig or in a boardroom can feel incredibly suffocating and lots of us tend to turn to virtual communities to find a sense of genuine representation.

As a successful mixed race musician, Nilüfer has taken a more cloak and dagger approach to navigating the inner workings of the industry. She’s asking herself “how can I, as a white passing person, be a useful ally to other minorities within the music community?” and “Can I learn to utilise the way I’m viewed differently in different contexts?” Her hope is to empower others and herself from the inside of the scene.

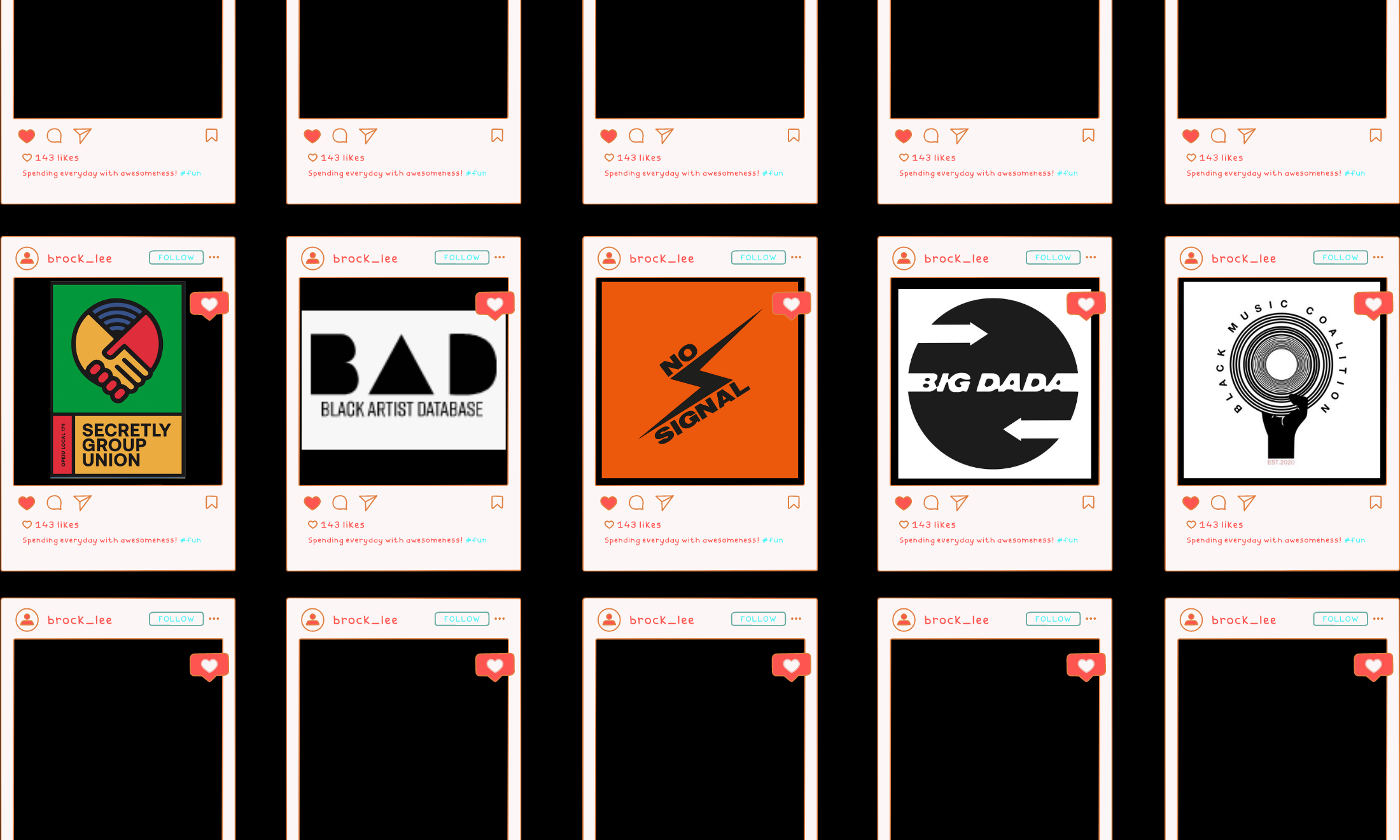

Melanie is using her position as an A&R to amplify Black alternative voices everywhere. “My last signing was an electronic Ugandan American, musician who lives in Kampala now, and I’m also looking at people in the alternative scene in Nigeria”. Amplification encourages Black fans to invest and reclaim their space in the scene.

“We all need to have deeper conversations. White people have to reckon with their whiteness”

Stephanie Phillips (Big Joanie)

While more Black artists are being proactive, white silence is still very violent. At times I even sense despondence from the usually spritely Shamir, and it’s something that I can relate to; like the apathy of whiteness dims our light. So the toughest question is really, what can white people do for us?

At the very least, Stephanie says, “they need to do the reading, we all need to have deeper conversations” and crucially “white people have to reckon with their whiteness and how they’ve benefited from it.”

To avoid harbouring toxicity like Ariel Pink, we have to weed out the obvious players when we see them. To this, Stephanie adds we have to watch out for the quiet ones: “It’s the people in your scene that act one way but in reality do a lot of damage without realising the effect.”

The whiteness of these spaces is a reminder of how our history in them hasn’t always been preserved – but it’s there. Alternative music is our space to occupy too. But ask yourself why you don’t see us at venues, why we opt to stay home and listen to the music on our own or with our virtual Black alternative communities.

Music is powerful and can bring communities together – but we have to feel safe in each other’s company before that can happen.

A year since Blackout Tuesday, here are the music initiatives still working against structural racism

After the ‘Peng Black Girls Remix’ erased Amia Brave, challenging colourism is essential

Can black artists counter music industry exploitation?