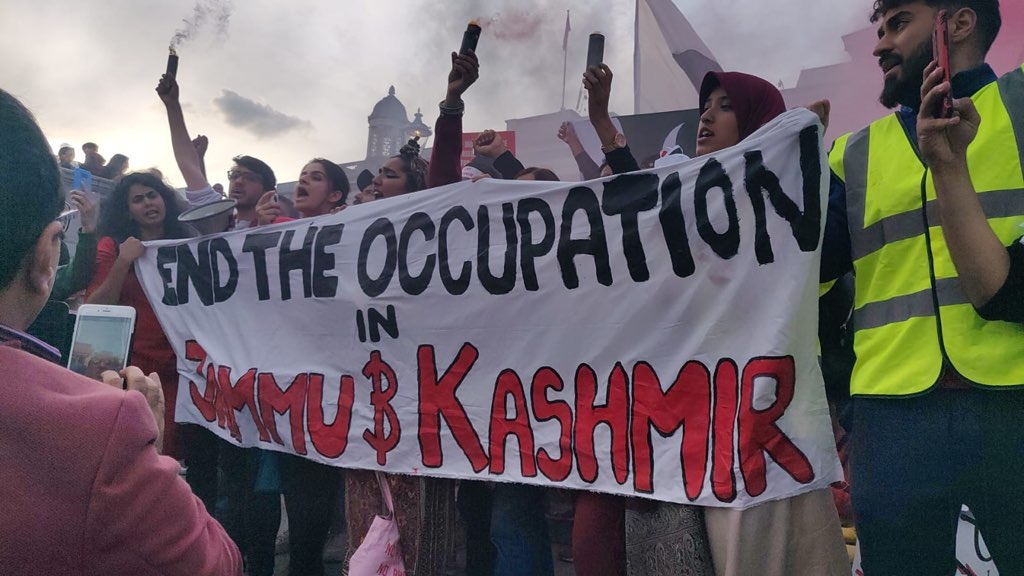

‘A tape put on our mouths’ – what it’s like being a Kashmiri woman in the world’s longest lockdown

It was painted by the Indian government as a positive move for women's rights in Kashmir, but over a year since the revocation of Article 370, Kashmiri women are being stifled mentally, financially and politically in the world's longest lockdown. They tell Sunny Shergill their stories.

Sunny Shergill

02 Sep 2020

Header photo of Kashmiri musician Nargis Khatoon, used with artist’s permission

Trigger warning: mentions sexual violence, domestic abuse and physical violence

When Kashmiri born-and-bred political anthropologist Dr Ather Zia thinks of Kashmiri women, one word comes to mind: “resilient”. This characterisation seems fitting, considering the decades of lockdowns, constant threat of violence and lack of agency that these women have had to endure. Despite the military conflict that rages against the once serene landscapes of the valley, Kashmiri women have withstood. They are taking back control of their narratives by bravely speaking out about their experiences through their work, and also in talking to us at gal-dem.

Globally, we have been forced to empathise with the Kashmiri people’s plight, adjusting to limited freedoms, living life on pause and in a state of indefinite uncertainty during the Covid-19 pandemic. There is a key difference, however, between the two lockdowns. As Arshie Qureshi, a Kashmiri woman tells me, “The one that is happening in Kashmir is not to save the lives of people, it’s to increase the [Indian] occupation day by day”.

“A Kashmiri lockdown looks different to the ones we have experienced, including curfews, increased militarisation and, most significantly, an internet shutdown that lasted around five months”

A Kashmiri lockdown looks different from the ones we have experienced. It’s included curfews, increased militarisation and, most significantly, an internet shutdown that lasted around five months. 2G has only just been allowed into the state.

Although lockdowns are not new to Kashmir, the region has had a long history of suppression, where the Muslim-majority state has struggled for autonomy. While the 1947 Partition of India resulted in Dogra leader Hari Singh choosing accession to India in return for Kashmiri autonomy, it has been “unfinished business” since. This can be seen in the series of wars that have been fought between India and Pakistan over the region and through the rise of insurgency by Kashmiri separatists who call for azaadi (freedom). Between the three competing nationalisms, the voices of Kashmiri women living in the region have often been suppressed.

Article 370 and the victimisation of women

While the repeal of Article 370 last year stripped Kashmiris of their promised autonomy, the Indian Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) argued this would be a positive move for women’s rights. A key issue was that, previously, if a Kashmiri woman had married a non-Kashmiri, she would have lost her rights to property. However, Ather tells me how “gender discrimination was used as a smokescreen”. While women had unequal rights in terms of property, this was based on a bureaucratic measure rather than law, and thus did not require a dismantling of an entire state to solve the problem. In fact, a High Court ruling in 2002 made it clear that a Kashmiri woman who married a non-Kashmiri did not lose her right to property or franchise.

Rather than focusing on the Indian perception of Kashmiri women as victims, Ather tells me of the progressiveness of the society and how literacy rates for women are 56.4% despite being a conflict zone. “The problem with Kashmir is that the situation is demonised so much, the men are demonised so much, that society is demonised so much. And it turns into this ‘saving Kashmiri women from the Kashmiri men’ kind of situation.”

Arshie Qureshi is a member of Mehram, a woman’s charity that tackles gender-based violence in Kashmir. She also refuses to believe that Article 370 was revoked for the benefit of women like her. She tells me about the objectification of Kashmiri women as “fair-skinned and beautiful” that is often held by Indian men. Disturbingly, she recounts a rise of tweets and songs on social media following the abrogation of Article 370 that Indian members of BJP “can now go to Kashmir and marry women”. She felt Kashmiri women were denied any agency, while these men tried to position themselves as saviours.

The safety of women compromised

Rather than improving women’s rights, Arshie argues the situation has become worse for women’s issues. Mehram have struggled to support women who are survivors of gender-based violence because, if the internet is shut down, how are women facing domestic abuse meant to contact the outside world for help? “The chain of communication was completely disrupted,” Arshie says. “We could not truly understand how they were doing, how they were keeping.” And, it’s not only lack of communication that proved to be so dangerous to women’s safety. As Mehram provides legal aid to survivors, accessibility to courts and freezing of lawyers “just became impossible”.

For LGBTQI+ Kashmiri women, the lockdown reduced the already limited safe spaces this community holds. Dr Aijaz Ahmad Bund, an LGBTQI+ activist, tells me how these marginalised people are “caught in a vicious cycle of patriarchy, LGBTQI+ phobia, armed conflict and religious fundamentalism”. Aijaz has written the first ethnographic study on Kashmiri Hijras, which was only recently published in 2017, showing how their existences often go unacknowledged, as though they were “invisible”.

Similarly to women’s rights, supporters of the abrogation of Article 370 argued this move would also benefit LGBTQI+ people. But shutting down the internet has compromised the safety of queer people – as Aijaz explains, lockdown has been “terrible for [those] facing violence (physical, emotional, verbal as well as sexual)”. Aijaz’s charity, Sonzal Welfare Trust offers support to LGBTQI+ people, including mental health services – so a communication blockade completely ruptured this support network. As Aijaz puts it, the Kashmiri lockdown has forced queer women into “isolation”.

“Kashmir is the most heavily militarised region in the world – for every one Kashmiri there are eight soldiers”

Ather believes the biggest threat to women’s safety in Kashmir is “military patriarchy and what that has done to women’s lives”. Kashmir is the most heavily militarised region in the world – for every one Kashmiri there are eight soldiers. Ather explains the work she is doing on enforced disappearances of men and how this affects the women who are left behind. Between 8,000-10,000 men have been deliberately disappeared by the military and government forces, according to the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). The term, “half-widow” describes the condition of a wife who does not know whether her husband is dead or alive, and thus lives in a state of perpetual uncertainty. This brings social issues too, as these women suddenly become the sole breadwinner. In this way, both Ather and Arshie argue women’s issues are interconnected with men’s issues and should not be seen as separate.

While women are more vulnerable to sexual violence from the armed forces, they are seen as a lesser threat and are less likely to be shot at than men. Ather explains that “women have become chaperones of men because there’s so much security discrimination against men”.

I spoke to Sara*, a 55-year-old housewife about her experiences of living in Kashmir all her life. She says, “I do not worry about myself but worry for the safety of my children and husband.” Sara recounts an incident where her 21-year-old son was a bystander to a stone pelleting that was targeted towards the police. Although he was not involved, he was beaten by the police with sticks and sustained serious injuries to his ear.

Sara is unmoved by the current lockdown, as she spends most of her time indoors. “It hasn’t made much difference to me. It was difficult to find jobs and it is the same today – in fact, there are even less jobs now.” The average unemployment rate of Kashmir in July 2020 was 17.9% – that’s twice the national average of 9.5%. Sara is disillusioned with the financial situation improving, as she tells me “the government gave us hope and what was promised didn’t happen”.

It is clear an atmosphere of fear and paranoia pervades the valley, fear for sons and husbands and fear of speaking out against the Indian government. I struggled to reach women who would be willing to speak to me about their experiences at all, and Sara’s desire to remain anonymous shows how that fear persists.

The cruelty of a communication blockade

Though internet shutdown brings many challenges – one of the most painful experiences is a lack of contact with family and friends. Arshie was in Delhi when the lockdown began and recalls waiting in long lines to have short conversations with her loved ones. “Imagine how brutal and how inhuman that is to have to wait for a queue to make a call in two minutes. For what reason?” She remembers, “It was really disturbing for me as a person”, as she deleted her social media apps during this period. “If I am not able to connect to the people who I want to connect with then there’s no point.” She proclaims, “It was a tape put on our mouth[s]”.

“Unlike this covid lockdown, being at home, you couldn’t even be in touch with your colleagues, friends and extended family. Our normal is very different from the usual normal”

Nargis Khatoon is a 21-year-old singer-songwriter who lives in Srinagar, Kashmir. The communication blockade impacted her education as well as her singing career. “Life turned upside down,” she says. “For me, the internet has always been a good deal to learn from – how could one even practice without it?” She relies on social media to reach her audience, so to have that cut off “was a big loss”. While she was meant to have graduated by the end of 2019, Nargis is still waiting for her last semester to begin.

Like Arshie, Nargis explains how the coronavirus lockdown is incomparable to the one Kashmiris face. “Unlike this covid lockdown, being at home, you couldn’t even be in touch with your colleagues, friends and extended family.” As Nargis aptly puts it: “Our normal is very different from the usual normal”.

The cultural depiction of Kashmiris

Kashmir heavily influences Nargis’ music. Historically, the region has been depicted as Jannat Par Zameen (heaven on earth), with its idyllic streams, sublime mountains and tranquil valleys. In her book, Territory of Desire, Ananya Jahanara Kabir explains how these cultural depictions of a paradisiacal Kashmir adds to the fetishisation of the region and why it is desired by so many. Bollywood’s representation of Kashmir toes between a romantic and peaceful landscape to a land riddled with militants. Films such as Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) and Mission Kashmir (2000) are examples of the evolution of this representation that mirrors India’s current political stance. Within this, Kashmiri women are presented as “pure” and “exotic” creatures to be conquered, mirroring the passiveness and lack of agency Arshie argues still exists today.

For Nargis, her home initially represented a paradisial place she was proud to come from. “Kashmir to me was the idea of a calm, serene state, the fresh air, the mesmerising weather, the beautiful places,” she says. However, after Article 370 was repealed, “it just changed drastically”. Rather than focusing on the place, Nargis’ music was inspired by “the people of my state, where I was suffering as an individual, others were suffering as individuals and [we were suffering] as a community.” Nargis has reclaimed her narrative, channelling Kashmiri experiences and their struggles into her touching and soulful ballads.

A hopeful future for Kashmiri women?

Speaking to Kashmiri women, it is clear that in the year since the revoking of Article 370, their rights have not been furthered. The lockdown that has been enforced on them has mentally, financially and politically attempted to stifle them. What they have shown is a resilience and strength in controlling their stories, far from their portrayal as victims needing to be saved.

“I just feel responsibility to put things out, to let people know what is happening, because you can’t always let the narrative be hijacked”

When asked about her outlook for the future, Arshie wishes she could be optimistic – but she’s not. “I think one year has been [a] complete standstill… it has not improved.” The cruelty of the communication blockade has just confirmed to Arshie “what value our lives had for [the] Indian state”. Despite apprehensions to speak out, Arshie demonstrates bravery. “[I] just feel responsibility to put things out, to let people know what is happening, because you can’t always let the narrative be hijacked.”

Nargis occasionally considers leaving Kashmir in search of further opportunities for her singing career. “We don’t have art schools here where one could actually polish their artistic skills… I do get to do shows here but even the live scene is very minimalistic, concerts happen on a very tortoise speed scale.”

Having lived in Kashmir all her life, Sara shows a strong attachment to her land. “I can never leave Kashmir. This is our motherland. The peace we find in Mauj Kasheer [Mother Kashmir] and amongst our Kashmiri people we cannot find elsewhere.”

A sense of patriotism and love for her land and people rings clear in Sara’s words. But what does belonging mean for these women when a military patriarchy threatens their existence on a daily basis? Rather than letting the “narrative be hijacked”, we must listen to Kashmiri women. They have a birth-given right to live in their homeland safely and freely. Sara’s words capture this poignantly:

“Kashmir is our mother. This culture, this Kashmir, I would not be able to find anywhere.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?