A white band said BLM but now they’re suing a Black artist for the rights to her name

Country band Lady Antebellum changed their name to be more racially sensitive. In doing so, they took the name of Black artist Anita White, who they're now suing. What can this tell us about performativity and the history of Black cultural ownership?

Rachel K. Godfrey

30 Sep 2020

Lady Antebellum photo from Wikimedia Commons, Lady A photo from artist’s album artwork

In June this year, country music group Lady Antebellum tweeted out that they would be changing their stage name after recognising some cultural “blind spots” and the racially charged associations with their name. Lady Antebellum joined the lengthy list of brands and artists who were making Black Lives Matter statements and offering lightweight support or nods to the movement.

Many of these companies, influencers and artists have been called out for showing cosmetic support via black squares, as well as business decisions that imply money may matter more to them than Black life. Take for example “women’s paradise” The Wing, who issued a statement of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, only to be exposed by former Black women employees who were subjugated to racist treatment by administrators, other staff and members alike. When businesses make statements like this, often they tell us way more about what people think is culturally appropriate, rather than their actual beliefs and practices.

“The band threw away an opportunity for potentially generative conversations around naming, ownership and erasure and reduced it into a quasi-spiritual, racially-propped journey”

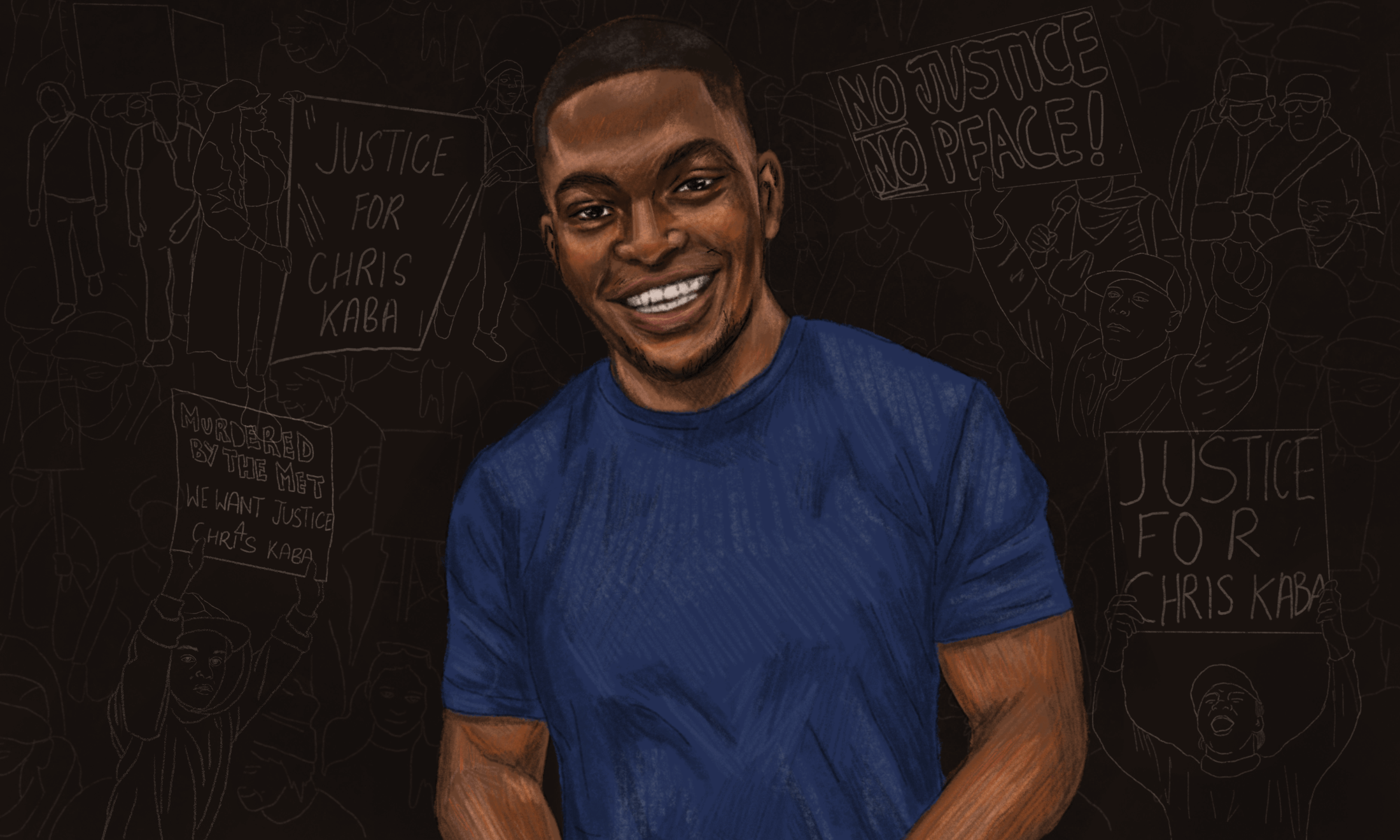

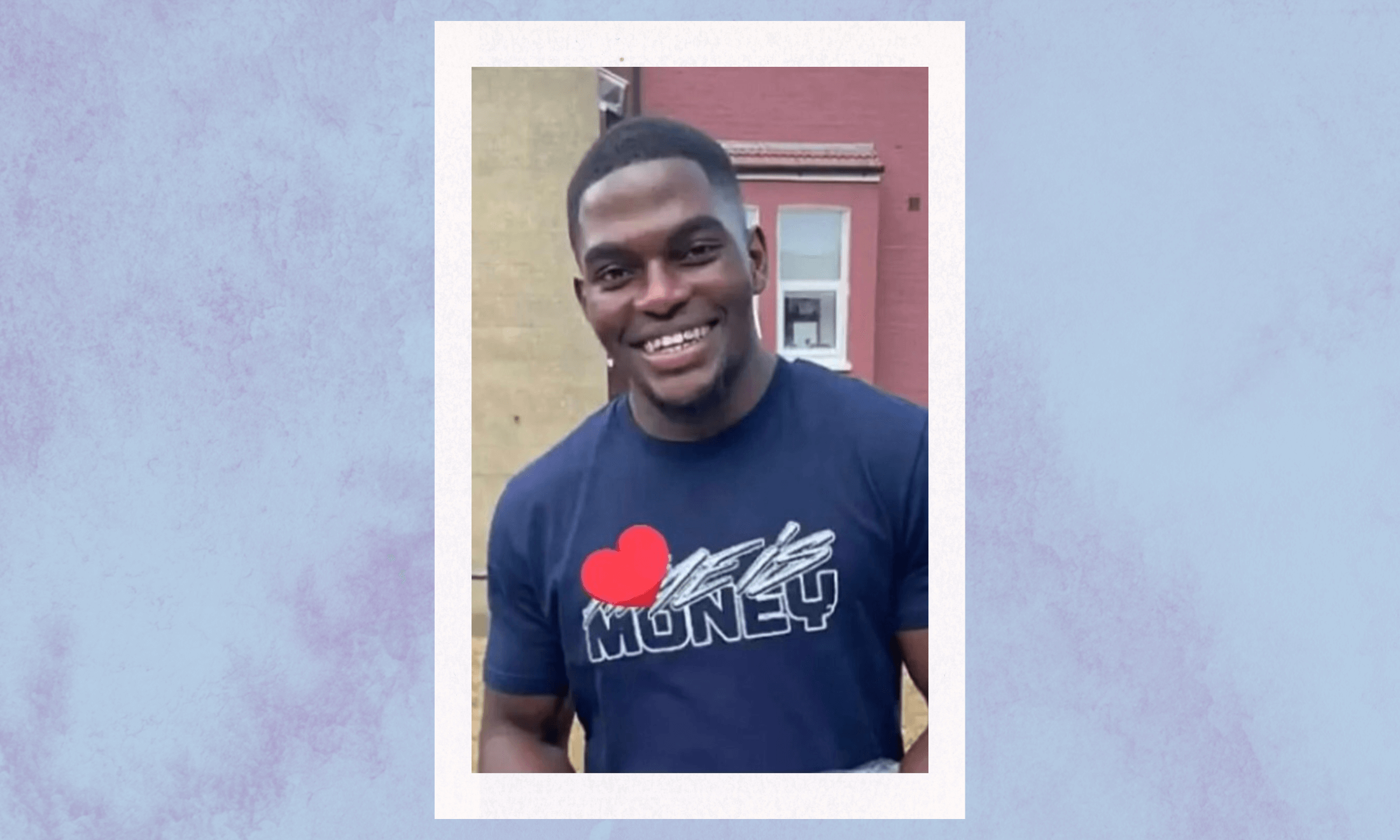

For their name change, Lady Antebellum shortened the group name to Lady A – the stage name already possessed by Blues singer Anita White. After they announced the change, the band reached out to Anita White about coming to a usage agreement. When told by her that she would not share her intellectual property without proper compensation – $5 million for her and $5 million for a charity whose focus is on racial equity – the band filed a lawsuit asking a court to grant them rights to share the name anyway.

Anita White was around 29 years old when she began performing under the stage name “Lady A”. In 1987, she began using the moniker, playing with Lady A & the Baby Blues Funk band for nearly 18 years. She hosted two radio programmes, played several sold-out shows and developed Lady A’s Back Porch Blues Showcase, an ongoing monthly show where her musician friends and emerging local artists could showcase their work. For years, Anita has built a strong following, a boisterous creative community and a strong sense of hope through her art and activism – all while using the name Lady A.

“White people have a history of taking control of Black people’s names”

The band – whose oldest member was about six when Anita White first performed as Lady A, 19 years before the group formed – stated that they chose their original name after taking their first photos at a “southern ‘antebellum’ style home” – also known as a plantation house. Combining the honorific title of “Lady” with the heavily romanticised “Antebellum”, band members Charles Kelly, Hillary Scott and Dave Haywood wrote the new chapter of an all too familiar story about the cultural erasure of Black people throughout America’s artistic histories. Very few batted an eye.

This romanticisation of the South in entertainment is nothing new. It follows behind years of Hollywood and literary “classics” that wistfully depict Southern plantation life as a charming and precious time. Ignored or neglected in films and stories such as Gone with the Wind, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and even Interview with a Vampire, is the extent to which subjugation, erasure and terrorism inflicted unto enslaved Black people was integral to pre-Civil War Southern society. The erasure is even more profound when we consider how much overwhelming support media like this gets. It’s difficult to fathom or ignore how a film as avoidant of the Antebellum South’s violence as Gone with the Wind could receive awards such as Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Cinematography, Editing and Art Direction, as well as two honorary Oscars. Through the States’ reaction to false depictions like this one, we can see the real, honest, racist climate in which Lady Antebellum and Lady A’s name controversy exist.

In an attempt to curb the inevitable backlash from their countersuit, Lady Antebellum released a statement to CBS News, wherein they described Anita’s refusal to give up her name for less than she thought it was worth as the inability “to join together with Anita White in unity and common purpose”. As of this month, Anita White is suing the band for the lost sales and diminished brand identity of them also using the name. It is only in the eye of the racist beholder that peace and silence could be expected of a Black person who is about to be robbed of something profoundly personal.

White people have a history of taking control of Black people’s names, something we can see in most places impacted by slavery. Every time we meet a Black American person with the last name Washington, Freeman, or Johnson, for example, the likelihood that their surname has a deep, ancestral fight attached to its story is very high. It wasn’t until after this romanticised Antebellum era that Black people could look into choosing their last name. We cannot ignore the genuine career-ruining implications for Lady A and her potential growth if an act with more capital, more resources and less identity-based bias and restriction takes over her name.

“Will legal ownership always trump cultural ownership, especially when the law was never designed to protect those most essential to our artistic culture?”

The Southern-born musical genres that Lady Antebellum cited as influential in their Twitter statement – “Southern Rock, Blues, R&B, Gospel, and of course Country” – were all birthed through Black livelihood. Black people’s joy, rage, sadness, resilience and war against erasure and racialised violence all went into forming these genres. The music they name as progenitors of their sound and presence is much more than just music, just as the Lady A stage name is much more than just a name.

According to Lady Antebellum’s legal team, the group successfully applied to trademark the Lady A name for usage on merchandise and other products, back in 2010. Their application to trademark, however, does not erase Anita White’s cultural ownership of the name. Their use of the law in this capacity beckons a crucial societal question: Will legal ownership always trump cultural ownership, especially when the law was never designed to protect those most essential to our artistic culture?

The band threw away an opportunity for potentially generative conversations around naming, ownership and erasure and reduced it into a quasi-spiritual, racially-propped journey – “We feel like we’ve been awakened…”, they wrote in their Twitter statement.

Careful and considerate anti-racism work of quality is not about “awakenings” within white folks. It’s about prioritising the needs of society’s most vulnerable and most neglected. Attempting to rob a Black woman of her creative and intellectual property does not fall under the anti-racist umbrella.

If Lady Antebellum’s reactionary rousing means putting the career of an artist who has been fighting for Black people since before they were born, I’d much rather they stay asleep.