Looking back at Burning an Illusion, the UK’s second-ever Black film

Menelik Shabazz’s twisted love story-cum-radicalisation tale is a flawed but important window into our collective past.

Memuna Konteh

13 Oct 2022

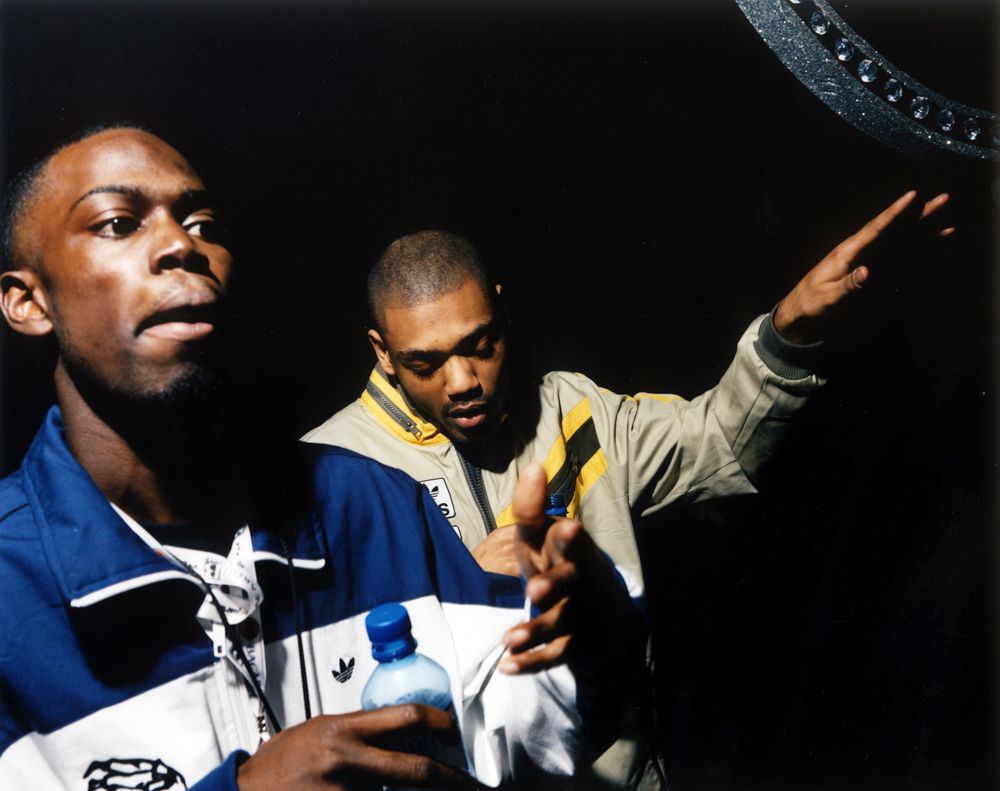

In 1981, Burning an Illusion became Britain’s second-ever feature film directed by a Black person. On face value, it is a love story, but it becomes clear there are uglier subterranean layers. It explores the discontent the new generation of Black Brits were feeling at the time, following the political awakening of the protagonist Pat Williams, whose worldview is radically transformed after her boyfriend Del becomes a victim of police brutality and Britain’s inherently racist criminal justice system. We see Pat evolve from a sweet, naïve, young woman with traditional aspirations of settling down and starting a family, to a woman scorned by injustice and determined to contribute to the burgeoning Black Power movement in the UK.

The project was a continuation of Menelik Shabazz’s passion for storytelling. Fresh out of film school in 1977, Shabazz made his directorial debut with Step Forward Youth. The documentary challenges stereotypes of Black youth culture by centering the voices of Black Britons. Shabazz wrote and directed the film at a time when Black British cinema was practically nonexistent. Having spent time on the set of Horace Ove’s Pressure – the UK’s first Black feature-length drama released in 1976 – he was inspired to create films that spoke directly to Black audiences about racial tensions in a period when Black British artistic expression was on the rise and anti-Black rhetoric and violence (fuelled by a budding National Front and newly-elected Tory government) seemed more pervasive than ever.

Despite his place in the Black British film canon, Shabazz is not a household name. But by revisiting his work 41 years since its original release, it’s clear that his first feature film, Burning an Illusion, is as timely as ever. And is now finally available to stream on multiple platforms to mark its anniversary.

The film is not perfect, Shabazz is at times heavy-handed with the narration, spelling out in voiceover points that the audience is more than capable of piecing together themselves. But its celebration of Caribbean culture, female friendship and Black British resistance ignites a flame in viewers. Here’s why you should revisit this piece of cinematic history:

It shows Black Britain through an autonomous lens

As the second-ever British film to be directed by a Black person, Burning an Illusion remains an important cultural touchstone of Black Britain and is highly revered by film critics and academics such as Dr Clive Nwonka. This is thanks to its authentic representations of Black life in London and the rare sense of nostalgia that it evokes. As one of the too few narratives encapsulating Black culture in the 80s, the film was met with excitement at the time by audiences who had never before seen themselves represented in such a light.

A Caribbean Times article on the 1982 London Film Festival for Independent Filmmakers, written by journalist Isabel Appio is quoted saying “the most overwhelming audience turnout was for Burning an Illusion, which had eager viewers spilling into the aisles.”

Everything from the soundtrack of reggae and lovers’ rock, to the language of the script (heavily sprinkled with patois), to the colourful costume and character aesthetics (tall, groomed afros, structured headwraps, an abundance of gold jewellery) makes the film an invaluable, cultural time-capsule. White people are present only in background roles and rarely speak in the film, which instead focuses on the complexity and contradiction of Black British identity at the time.

The film was shot entirely on location around Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove, one of Britain’s most vibrant Black communities. We get insight into just how tight-knit that community was all those decades ago. We’re graced with heart-warming scenes in Black-owned restaurants, rammed full of Black patrons eating and gisting in red leather booths; dancehalls and parties brimming with Black people dancing and jubilating until the early hours; community bookstores and rec centres where Black people gather and relax, free from the inhibition imposed by the white gaze. Though the film was intended to show all that there is to gain in terms of Black liberation in the UK, watching it today, there is an unavoidable sense of grief for all these community spaces that have since been lost to gentrification.

In Burning an Illusion, Shabazz presents issues facing the Black community, such as unemployment, alcoholism, gambling and knife crime without judgement or justification, while still honouring the softer more universal aspects of realistic love. He could be considered a founding father of British cinema in our community. His films, advocacy and initiatives such as Black Filmmakers magazine and BFM International film festival paved the way for the likes of Steve McQueen, Theresa Ikoko, Michaela Coel and Kolton Lee who, following Shabazz’s death in 2021 said: “[Menelik] became a constant source of inspiration to me as well as a kind of elder, who had walked the path that I was walking and had words of advice, encouragement, support, and insight.”

“Everything from the soundtrack of reggae and lovers’ rock, to the patois in the script, to the colourful costume and character aesthetics (tall, groomed afros, structured headwraps, an abundance of gold jewellery) makes the film an invaluable, cultural time-capsule.”

The film has a female protagonist

Burning an Illusion centres a Black woman in a way that was basically unprecedented at the time. Yet this aspect of the film has aged poorly, with arguably a failure to critique patriarchy and misogynoir. Perhaps due to the fact that it’s a man’s view of womanhood. At the beginning of the film, we see Pat portrayed as self-determined and independent, making it all the more disappointing to watch her steadily morph into the long-suffering, ‘ride-or-die’ Black girlfriend trope.

Pat supports Del after he’s kicked out of his parent’s home and loses his job. She takes him back after he slaps her for apprehending his open disrespect of the home she pays for and allows him to stay inDel’s abuse of Pat is minimised in that it’s never referenced and we’re expected to empathise with him and root for the couple after he’s imprisoned, without him offering any repentance. Domestic abuse and chauvinism are treated with a casualness that sours any sense of romance from the central relationship in the film.

The fact that Pat’s character arc is so obviously shaped by the experiences and perspectives of her boyfriend falsely implies that Black women can’t recognise racist oppression without the encouragement of a man. At one point she even says, “his interest in books was rubbing off on me,” and proceeds to bin all of her Mills & Boon novels in favour of Black revolutionary texts. This insistence that a politically engaged Black woman can’t indulge in smut or glamour continues throughout the film, as we see Pat (formerly an aspiring beautician) drastically tone down her look, to the delight of Del who remarks at her braids: “That’s how mi like you… my African woman”.

A redeeming factor is the uplifting portrayals of Black sisterhood. Pat and her friends, Sonia and Cynthia, are all wildly different in sensibilities and temperament but their commitment to each other makes for a protective and strong support system. Some of the most endearing and funny moments in the film occur when the women are alone together. The bond that they share is one that can be universally understood by Black women anywhere. That, alongside the brief but impactful portrayal of a lesbian couple enjoying Janet Kay’s performance of ‘Imagine That’ at an intimate concert, shows the director had sincere intentions of making a progressive film even if he falls significantly short by today’s standards.

The fire against police brutality and systemic oppression rages on

The relevance of Burning an illusion in Black Britain today can be seen in the ongoing fight against police brutality and the country’s skewed justice system. The murder of Chris Kaba and countless Black people like him who have died at the hands of British police show that the white supremacy that Shabazz mounts in the film is still a blemish on society today.

Films like Burning an Illusion allow us to grieve and embolden us to act. They are reminders that resistance takes many forms, reminders that nobody sees us as keenly as we see ourselves and that no one can speak for us as we speak for ourselves. We must cherish these cultural klaxons because they jolt us into the truth that the struggle is as enduring as it is urgent.

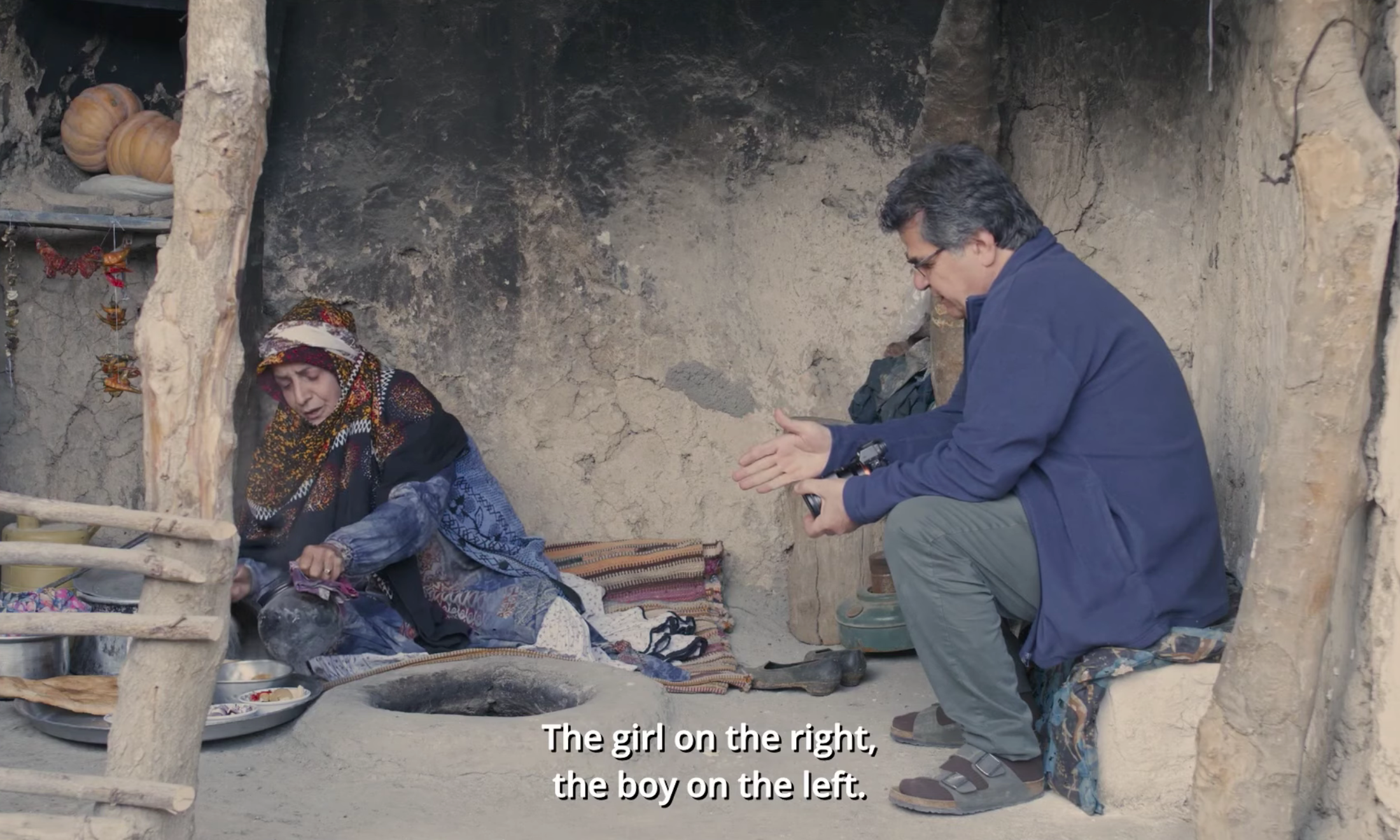

Watch a clip below:

For the first time ever, Burning an Illusion is available to watch in high definition on Blu-Ray and streaming platforms, BFI Player, Amazon Prime and iTunes.