Anu Ambasna

UNESCO’s new World Heritage Site in Madrid was once a racist human zoo

Behind the beautiful facade of Retiro Park's Palacio de Cristal lies the dark history of when a tribe from the Philippines were exhibited.

Leah Pattem

18 Aug 2021

On an April morning in 1887 in Madrid’s Retiro Park, Queen María Cristina declared the Exhibition of Philippines open for business. Over the course of six months, tens of thousands of Spaniards would have the chance to visit one of the farthest corners of the Spanish Empire – and even meet some of its people – without ever having to leave the country.

The grand inauguration of this exhibition took place in the Palacio de Cristal (Crystal Palace) – a beautiful, giant greenhouse built to house tropical plants brought over from the Philippines. Textiles were also added, as museum curators laid out paths using rugs woven by Filipino women. It was not just these items on display: the people who crafted them were too.

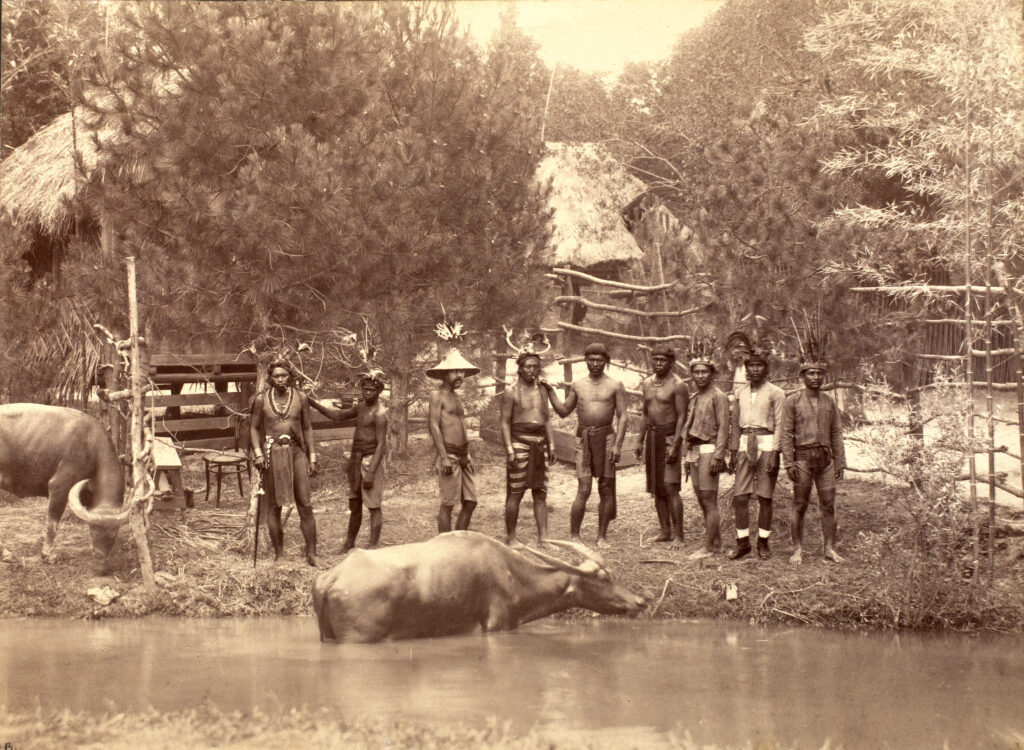

Spanish colonisers brought 43 Igorot women and men from the mountainous island of Luzon in the Philippines, instructing them to act out their daily lives in front of spectators. A small village was built for them next to the palace, complete with streets, raised thatched huts and places of worship. A pond was dug in front of the palace and filled with water and fish for the Igorot people to catch. Traditional canoes made of hollowed-out tree trunks sat at the water’s edge. Small farms were laid out and cattle were brought in to plough the land, all for the amusement of curious onlookers.

“You cannot judge the past from the lens of the present because people were different then – their view of the world is different from ours today,” says Ambeth Ocampo, an academic and former chairman of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Now, with UNESCO granting Retiro Park prestigious World Heritage Status in late July, community activists are drawing attention to what lies beneath the site’s lush greenery and its impressive glass centrepiece, pushing for that racist world view from the past to be put into context for today.

Unchallenged racist narratives

The Spanish colonisation of the Philippines began in 1521 and lasted until the Philippine Revolution in 1898, sparked by revolutionary leader José Rizal’s writings. Following the Spanish-American war, the United States took possession of the Philippines. The main European language learned in Filipino classrooms today is English, but as recently as a few decades ago, it was Spanish, demonstrating the enduring influence Spain had in the Philippines for almost four centuries. Even today, streets in cities and towns across the archipelago remain named in Spanish. Walk around the neighbourhoods of Manila and you could be mistaken for thinking you were in the barrios of Madrid.

The Exhibition of the Philippines was predominantly driven by profit, but also sought to justify to the Spanish public the work that missionaries and traders were doing in the colonies. Despite some of the Igorot people living day-to-day in ‘Western’ clothing and working service-sector jobs back home, in Madrid, they were required to wear folk costumes, carry spears and perform daily ceremonies involving the sacrificial slaughter of animals.

A pamphlet produced by Spain’s Ministry of Culture for a 2017 exhibition revisiting the original 1887 Exhibition states that this “reaffirmed stereotypes surrounding these people, who were considered primitive or savage throughout the ‘civilised’ world of the day.” The document contains the few surviving photographs of the 43 Igorot people. These staged images involved nudity and dramatised aggression, presenting a racist narrative that goes relatively unchallenged even today, especially in Retiro Park itself.

Now, in 2021, a small, weathered plaque is positioned near the Crystal Palace, immediately beside a wooden platform for terrapins bathing in the sun. The plaque mentions the architect who built the palace, gives details of its size and composition, and even includes an illustration of the plants adorning the inside of the palace during the Exhibition of the Philippines. What the plaque fails to mention, however, are the people who were displayed inside.

“Ignoring the past or remaining anchored to a 19th-century view that is rooted in scientific racism dehumanises us”

Alicia Torija

Upon UNESCO’s announcement that Retiro Park is gaining World Heritage Site status last month, members of Madrid’s Filipino community felt the need to take action. Alexis Lahorra is a Madrid-based Filipino-Canadian activist calling for greater inclusion of Filipino narratives in Spanish history. “The point of UNESCO is to preserve and protect, through education and culture, a universal respect for human rights,” she says. “Why is it that we’re not protecting the people who were in the exhibition? Their dignity was taken away. By remembering them, we can at least try to recover some of that.”

Alicia Torija, a member of the Madrid regional assembly from leftist political party Más Madrid, says: “If these people aren’t recognised as a historical subject, that amounts to a democratic deficit. We cannot allow whiteness, Eurocentricity or homogeneity to be the characteristics that prevail […] Ignoring the past or remaining anchored to a 19th-century view that is rooted in scientific racism dehumanises us.”

The pain and profit of ‘ethnic shows’

Between the mid-19th and 20th centuries, exhibitions of indigenous peoples from colonised territories were popular throughout Western Europe and the United States. Some exhibitions were marketed as ‘ethnic shows’, which is how academics and historians generally regard Madrid’s Exhibition of the Philippines. That language might be more palatable to some today, but the reality is that these ‘shows’ were human zoos, rooted in racist colonial endeavours.

In other cities, such as Berlin, London, and New York, human zoos were advertised as such. They encouraged the public to be afraid of the people exhibited, referring to them as ‘cannibals’ and keeping them behind fences. Both displays encouraged the Western world to observe ethnicities and cultures that were different to their own – and to exoticise, degrade and fear them.

Ethnological exhibitions of all sorts were highly profitable undertakings, and many travelled around Europe and the US. Another ‘ethnic show’ invited to Retiro Park, this time from outside the Spanish colonies, featured people from Guinea and Ghana in an ‘Exhibition of the Ashantis’ in 1897. Contemporary reports suggest that a later human zoo featured Inuits from northern Canada. All ethnological exhibitions are poorly documented, but evidence of their existence can be found in Madrid’s National Museum of Anthropology.

“It’s not entirely surprising that ethnological exhibitions are something a nation might want to collectively forget”

The ground floor of the museum is dedicated to the Exhibition of the Philippines and contains around a hundred artefacts, including crockery, tools, weapons, ornaments and clothing as well as maquettes of vehicles, all dating back to 1887, as well as two of the original tree-trunk boats used in the 19th-century exhibition. Despite the inclusion of Igorot artefacts, there is scant reference to the Igorot people, apart from a few words beside the boats mentioning the “Filipino crews” who took visitors for boat rides on the pond they once fished in in Retiro Park.

It’s not entirely surprising that ethnological exhibitions are something a nation might want to collectively forget. Framed in both the past and present, displaying people for their race is a shameful act – one that journalist and anti-racism activist Lucía-Asué Mbomío Rubio believes is important to acknowledge. She explains that human zoos and ethnological exhibitions are directly linked to racist attitudes held by the public today. “They justified invasions based on the belief that the population was inferior” she says. “They justified the enslaving of Africans by claiming that the people didn’t have a soul.”

Lucía-Asué, whose father was born in Guinea, also points out that, often, the names of people in the human zoos popular across western Europe and the US throughout the 19th century were never recorded, and that the people were typically grouped by ethnicity rather than by their country of origin. “Their anonymity dehumanises them, just like with the thousands of refugees arriving by boat into Spain today.”

‘Recognising our memory’

The views of Lucía-Asué and activist Alexis echo those of José Rizal, a national hero in the Philippines whose time studying medicine in Madrid coincided with the 1887 Exhibition. “While Rizal rightly raged against the exhibition, he did not actually visit it,” says Ambeth, the academic. “The Spanish view [now] is that it was not just a display of the land and peoples of their far-off colony, but also a way to emphasise Spain’s civilising and Christianising work in the Philippines.” Rizal’s indignation at the treatment of the Igorot people in Madrid is believed to have inspired writings that sparked the Revolution of the Philippines in 1888 – ultimately leading to Philippine independence.

Almost 150 years later, Spanish society and institutions are still battling with how to contextualise the past. “Rescuing, preserving, demanding and recognising our memory is not only a right but also a duty,” explains regional politician Alicia. “Only if we know the history of the forgotten, ignored and oppressed can we fight against stories that are manipulated or whitewashed. This duty must be incorporated into policy that requires this history to be included in books and in classrooms,” which is something the Spanish government has already begun doing in order to come to terms with its more recent history.

Spain’s Ley de Memoria Historica (Law on Historical Memory) was passed in October 2007 and amended this summer. The government will now fund attempts to better and more accurately recognise those who suffered persecution or violence during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the subsequent dictatorship, which ended in 1975. The amendment includes more thorough documentation of victims and updating school textbooks to no longer perpetuate the idea of symmetrical responsibility. Grassroots activists hope similar institutional change and recognition will come for other marginalised communities and stories.

“So far, the public reaction to the park’s new status has been one of celebration, but this has only served to bury the site’s racist history even deeper”

“Retiro Park’s new UNESCO status means it’s now on the world stage, and I think the last thing UNESCO or Madrid’s City Council want is for people to know the park was the site of a human zoo,” says Angelica Pfleider, a Filipino activist working with Alexis. “Being declared a World Heritage Site could distract from its history.”

UNESCO’s granting of World Heritage Status to a site with such dark histories raises a bigger question about the role this institution plays in recognising historical human rights abuses. So far, the public reaction to the park’s new status has been one of celebration, but this has only served to bury the site’s racist history even deeper, and many local activists and historical memory experts, including those who spoke with gal-dem, agree.

This community hopes that UNESCO will assist Madrid City Council in updating the plaque outside the Crystal Palace to acknowledge the 43 Igorot people who were part of the Exhibition of the Philippines, as well as those who featured in further ethnological exhibitions. They hope that the story of Madrid’s human zoos will be incorporated into school textbooks so that generations to come can realise how tangible Spain’s historical persecutions were and are regarding racially marginalised communities in the country today.

These issues resonate beyond the painful history of the 1887 Exhibition and the treatment of the Igorot people. Madrid’s Roma community remains largely segregated today, and Roma activists are asking for the 1749 “Roma Raid” and ethnic cleansing, where 12,000 Roma were killed, to be taught more widely, and for the street named after the Minister of War who ordered the raid to be changed. Indigenous Latin American people living in Madrid are asking for recognition and reparations 500 years on from the Spanish invasion of present-day Mexico City, and for the Spanish army to scale back its military parade on 12 October, the day that Christopher Columbus “discovered” the Americas.

For the community pushing for the recognition of the Igorot’s presence and treatment in Retiro Park, the fight continues. “Acknowledging the human zoos in Madrid’s Retiro Park will show other racially marginalised groups, such as Roma people and Indigenous Latin Americans in Spain that it’s also possible to acknowledge what was done to them in the past,” says activist Angelica. “If we’re successful, it could give others the courage and inspiration they need to seek the truth about their own history too.”