One year on, we must remember the Essex 39 and fight for justice for migrants

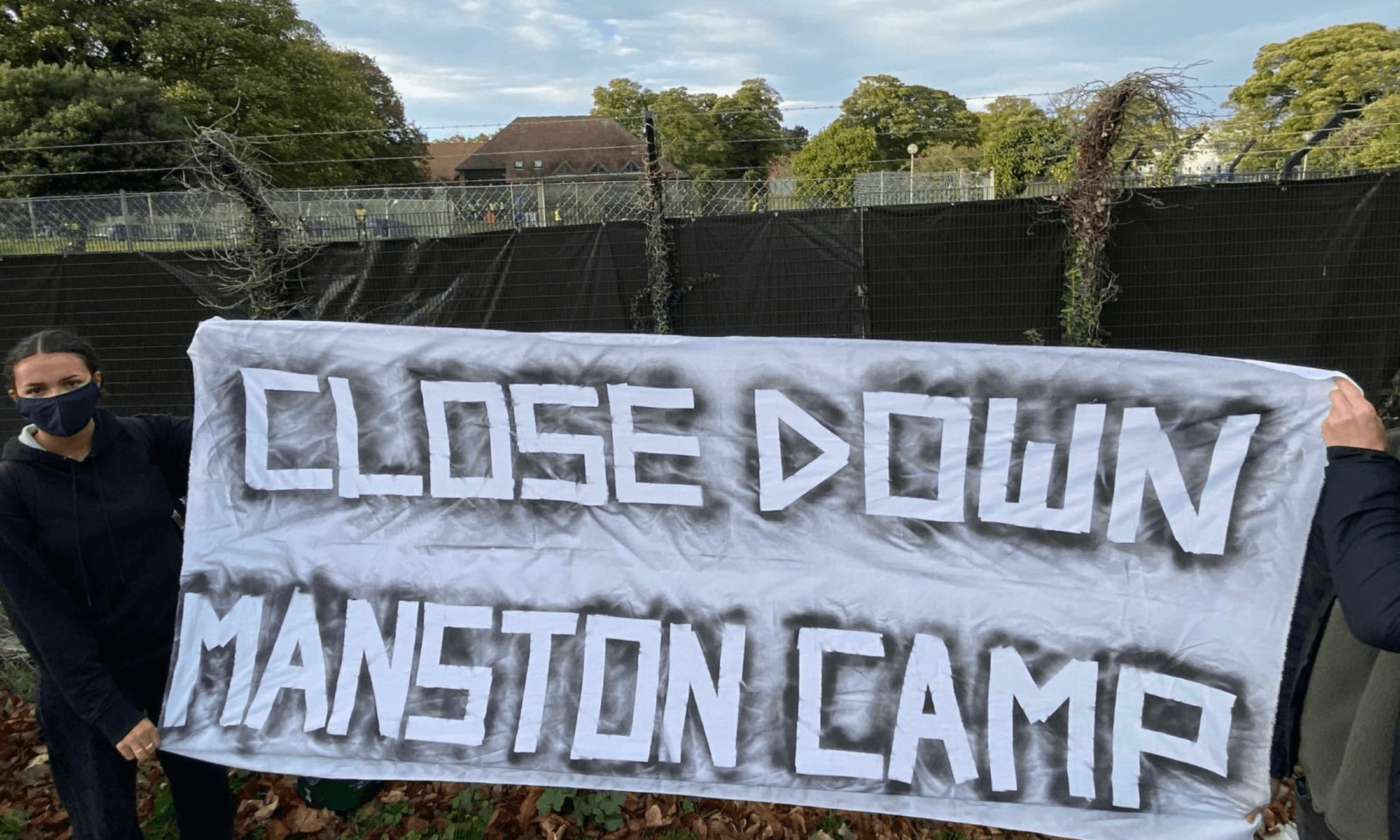

The UK’s ‘Hostile Environment’ policies continue to violently exclude the most vulnerable in our society.

Remember the Essex 39 Campaign

23 Oct 2020

Illustration by Roshi Rouzbehani

One year ago today, 39 Vietnamese nationals were found dead in the back of a refrigerated lorry in Essex. The lorry had crossed the Channel from Belgium, a route that has been used increasingly by migrants after the French government tightened restrictions on departures from Calais. These 39 people, the youngest of whom were two 15-year old boys, had intended to come to this country to carve out a better life for themselves and their families. In the end, they were killed by the UK’s racist and violent border policies.

After hearing about the 39 deaths, the Remember the Essex 39 Campaign came together to hold a vigil outside the Home Office. We gathered to grieve as a community and hold space to mourn for those who lost their lives, and also to make it very clear that the deaths of the Essex 39 were not some unavoidable tragedy, but a direct result of British state policies — like the deaths of Jimmy Mubenga, Joy Gardner, Abdulfatah Hamdallah, Mercy Baguma and countless others.

Politicians across the political spectrum claimed to feel grief and sadness at the deaths of the 39 migrants, yet in the same breath advocated for tougher border controls to prevent similar fates from befalling others. Two drivers are currently on trial for “conspiracy to assist unlawful migration”, manslaughter, and other more minor offences.

“Border enforcement makes migration ever more deadly and creates the demand for smugglers”

Regardless of the result of the legal case, we know that punishing individuals is simply a way for the government to provide the illusion that justice has been served, without having to interrogate its own complicity. Contrary to what certain politicians have suggested, it is precisely tougher border enforcement that makes migration ever more deadly and creates the demand for smugglers. The only way to prevent death is to create safe and accessible routes of entry.

Individual prosecutions and framings of tragic victimhood also obscure the structural reasons for these people’s deaths. On the one hand, the initial media push to conflate human trafficking with smuggling in relation to the Essex 39 ignored these migrants’ agency. Although the concepts do not have clear boundaries, trafficking implies forced movement for the purposes of exploitation, whereas smuggling generally does not. In addition, as we know from sex worker and domestic worker movements, anti-trafficking initiatives often end up criminalising and punishing victims, actively worsening their situations, rather than protecting them. This is because the expansion of law enforcement and the conducting of “rescue raids” on nail bars and cannabis farms under the guise of “anti-trafficking initiatives” can result in the apprehension and detention of migrant workers, who then either face deportation or a protracted legal battle to remain.

On the other hand, the archetype of the Asian economic migrant, as opposed to the “genuine refugee”, entrenches the distinction between the undeserving and the deserving migrant: those hoping to come to the UK to work in low-paid work are seen as preying on domestic jobs, which in turn jeopardises the rights of people fleeing persecution to enter Britain – ignoring the underlying context of global capitalism that pushes people to migrate in the first place.

Indeed, many migrants to the UK, including these 39 Vietnamese migrants, come from places suffering ongoing extraction and exploitation in which the British state is and has been complicit, and from which it continues to reap the benefits. Global capitalism creates the conditions for labour migration, then marginalises and makes migrant workers vulnerable to exploitation and fundamentally disposable. We need to recognise this violent system is working exactly as it is supposed to.

“Even if the Essex 39 had survived their journeys here, they would have been subject to the slow violence of the border”

Even if the Essex 39 had survived their journeys here, they would have been subject to the slow violence of the border, which doesn’t make headlines at all: they would face exploitative and dangerous working conditions, in addition to the risk of immigration raids, detention and deportation. In 2004, 23 cockle pickers drowned in Morecambe Bay after being forced to work at high tide. More recently, the Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the fact that many migrants suffer premature death due to unsafe working conditions, lack of access to healthcare and public funds, overcrowded housing, and overwork.

The British government’s promises of immigration reform are and have always been empty. This is demonstrated by the fact that in 2000, 58 Chinese migrants were found dead in a sealed, airless container in Dover, in conditions all too similar to those experienced by the Essex 39. Since its founding as a bordered nation-state, Britain has attempted to control migration for its own gain, at the expense of real people’s lives: countless examples, from Windrush to the Home Office’s recently revealed proposal to house migrants on Ascension Island, to its ongoing enforcement of detention and destitution of migrants, show that the British state’s policies are rotten to their core.

This is why reform is not enough – our struggle must have a clear abolitionist horizon. We believe that people should be able to move without risking their lives. For this reason, we believe in a world without borders, without prisons, without police, without nation-states. We believe these structures, which were established as mechanisms of imperial control and extraction, must be dismantled, as part of a broader transformation of our political and economic system.

In remembering lives brutally cut short by borders, racism, and capitalism, we resist against the conditions that lead to premature death.

Join us in a show of remembrance and solidarity: post a photo with the words “Remember the Essex 39” on Instagram @remember.resist and Twitter @remember_resist and use the hashtag #RemembertheEssex39.

If you live in or around Hackney, the Hackney Chinese Community Services is holding a shrine to commemorate the deaths of the Essex 39 on Friday (23 October), which you can visit anytime from 10am to 5pm at 28-32 Ellingfort Road, London E8 3PA.