Author

The pressures of passing on a religion when you’re the last of your kind

When your religious community is dwindling, continuing faith becomes a difficult pressure to navigate.

Maheen Behrana and Editors

21 Jan 2021

When I was in primary school, I gave a talk about my religion, Zoroastrianism. I was bursting with pride. “You can’t just become a Zoroastrian,” I said, “you have to be born one.” I showed the class copies of our holy book and told them how we celebrated our new year, Navroze, at the spring equinox. “I get two new years!” I said, “And two birthdays!” Zoroastrians have their own religious calendar, meaning that I get an ‘English’ birthday every year and a religious one a few days earlier. I felt pretty smug – everyone else wanted two birthdays too.

Today, I feel very differently about my religion. My pride is more complicated and I struggle to reconcile myself – and my future – to its strictures.

Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest religions, with roots in ancient Persia. My family are Parsis – descended from Zoroastrians who fled ancient Iran after the Muslim conquest of the Persian empire and sought refuge in the Indian subcontinent. Parsis settled there on the grounds that they would never intermarry with local communities nor attempt to convert anyone. Many Parsis still abide by these tenets today, meaning that the worldwide Parsi population is tiny, at just 200,000.

Growing up, I was always told that I must marry a Parsi and pass on the faith. While six-year-old me was happy with this rule, 16-year-old me was not. To my surprise, my parents were very supportive of my choices, although my mum told me to keep my opinions quiet from my extended family. I think she realised that for some time, I had felt disillusioned with the Parsi community. The exclusivity I had prided as a child felt suspiciously like supremacy as a teenager.

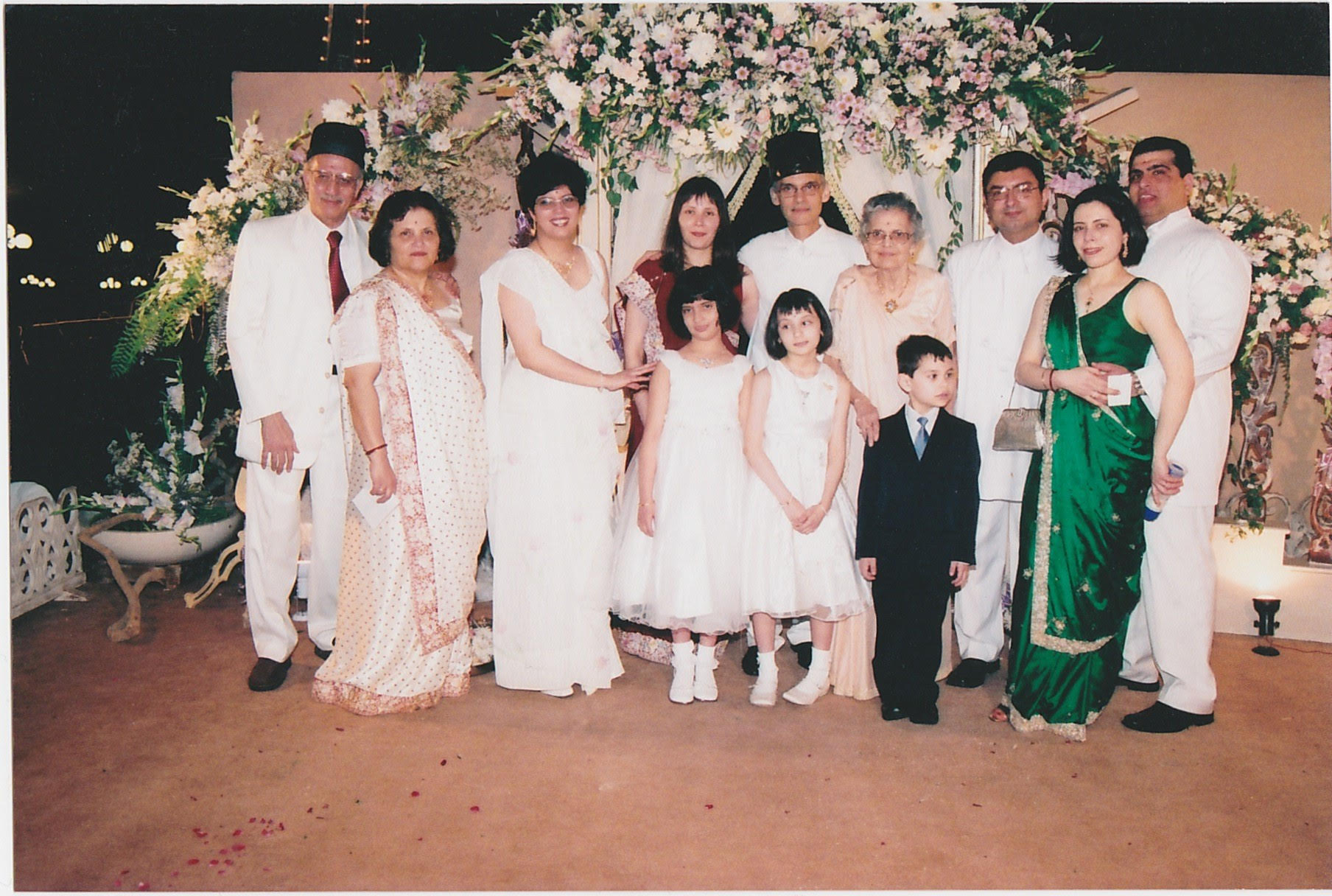

In all fairness, I didn’t know my community well. My family never socialised with any other UK Zoroastrians (there are just 4,100 of us) and religion was always a private thing for us. There are no Zoroastrian temples in the UK, and few cultural centres around which to congregate. I mainly met other Zoroastrians abroad – in Pakistan or America – where my extended family would meet up for weddings and Navjotes (confirmation ceremonies). Over time, I became troubled by some of the attitudes I saw on display. I hated to be told I was “marriageable“ purely because of my pale skin and my ears would burn at the overtly racist “jokes“ older Parsis would casually throw around. I was disturbed by the homophobia of kindly uncles and the internalised misogyny of smiling aunties.

Also upsetting were the hardline attitudes towards marrying out. Many said it was stupid when we had been blessed to be born Parsis. We had a great duty to pass on our ancestry and have Parsi children.

“I want to pass on my faith because it’s important to me. It has brought me hope, comfort and purpose at times when I have struggled to find any”

But as things stand, it doesn’t look like I’ll be doing that. I’ve been with my white (areligious) British boyfriend, Craig, for over three years. On our most recent trip to America, my mum told my grandmother about him, feeling unable to hide my ‘secret’ any longer.

Nani was outraged over the fact that my mum was allowing me to have a relationship before marriage, and with a non-Parsi of all people. But she was also sad because of what she thought I might lose.

If I marry and have children with Craig, I will no longer be deemed a Parsi by many in the community. I will likely be refused entry to our fire temples abroad and my children will probably be refused a Navjote.

I may not follow Zoroastrianism to the letter, but I feel a deep connection with it. I pray our ancient prayers whenever in need of comfort. I love the little rituals my mum carries out – the chalk patterns she draws in the hallway on auspicious occasions, the sandalwood incense we burn. But most of all, I do and have always believed in God – and my faith is a framework through which I navigate that belief.

I desperately want to pass this on to my children. Not through a sense of obligation to my heritage – I left that feeling behind in my teenage years. I want to pass on my faith because it’s important to me. It has brought me hope, comfort and purpose at times when I have struggled to find any. My children will likely not be ‘ethnic’ Parsis but Zoroastrianism is first and foremost a belief system. What should someone’s genetics have to do with it?

Fortunately, my extended family have come round to Craig. They wish him happy Navroze and include him in their prayers. But my family is not the wider community.

I’m not a believer in dogma and doctrine, but I want to make sure my children have spiritualism, prayers and rituals to turn to, and I will try my best to that end, with or without community support. But if the Parsi community refuses to open its doors to me and my future children, I won’t have abandoned my dying faith – it will have abandoned me.