Aude Nasr

Celebrating a new era where pop music doesn’t just mean ‘white’

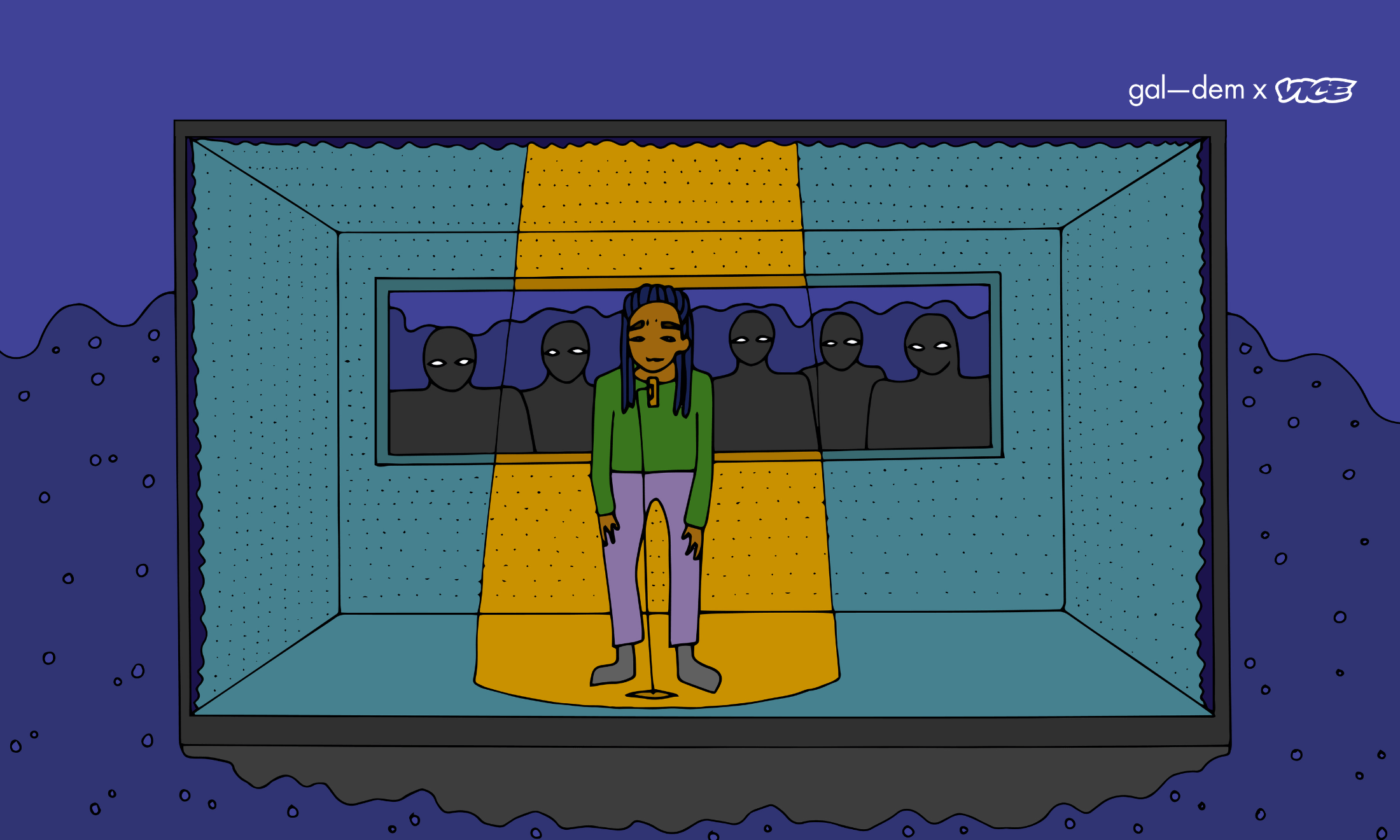

Speaking to artists, publicists and fans, Melissa Kasule explores the changing face of pop stars and stans, considering how the Western music industry has failed people of colour by centring whiteness for so long.

Melissa Kasule

28 Oct 2020

The world was left mesmerised by Normani’s flexibility in ‘Motivation’. Chloe X Halle’s backyard tennis court has become as renowned as Wimbledon. Einstein has been shamed and outclassed since Rina Sawayama invented musicality.

With an increasing turn of critically-acclaimed work, this is a new age of pop with people of colour (POC) at the centre.

The bondage of my teen years dedicated to One Direction ended in August 2015 when Zayn Malik came out with the news he was leaving the group, shortly followed by the boyband’s announcement that they were going on a “break” (men really do lie unprovoked). Yet, in all its despair, there was relief.

Zayn made his struggles while in the band increasingly clear and I can’t help but think his being the only person of colour in the group played a factor. As a fan, even their music videos could make me feel less than adequate – in the music video for ‘Night Changes’, you were taken on “dates” with the boys, but this point of view-style shoot featured white hands to represent the viewer.

And so, when Zayn left pop music, I followed shortly after (admittedly, I was still a Harry girl).

“There is a new, profound sense of freedom to fully engage comfortably in pop music in a way I never had the chance to do before”

But something is changing: I’ve returned to a space full of burgeoning POC artists, corresponding with a growing POC fanbase. There is a new, profound sense of freedom to fully engage comfortably in pop music in a way I never had the chance to do before.

The ostracising of ‘foreign’ pop

In One Direction’s absence, amidst a collapsing Western industry of boyband and girl groups, curly-haired white boys were replaced with Korean pop idols. BTS beat Taylor Swift’s record of most-watched YouTube video in 24 hours, BLACKPINK had every track on their debut album in the Top 200 Global most streamed songs on Spotify, while K-pop’s fandom stay shutting down Twitter. The international force that is K-pop is undeniable, yet it’s often treated as a point of a concern. It urged pop mogul Simon Cowell to launch X Factor: The Band, on the basis that, “Right now K-Pop, you could argue, is ruling the world. Now it’s time for UK-Pop.”

“There’s a deliberate move to keep K-pop as this ‘foreign phenomenon’, occurring from outside the pop genre”

An entertainment industry led by white people for so long sees it as unacceptable for anyone not white to govern the sound. This consistent ignorance bumps K-pop acts out of the most competitive categories at awards ceremonies, overshadowed by white performers or tagged into “foreign” categories. It’s a deliberate move to keep K-pop as this “foreign phenomenon”, occurring from outside the genre. It forces K-pop acts to compromise in making music in English or collaborating with white artists in order to be validated as pop.

As Natasha Mulenga wrote for gal-dem last year, “The gatekeepers of some of these award shows are well aware of the fact that if they were to put Korean artists in the same music category as the Western artists, they would easily win. They will not allow the status quo to be broken.”

Bree Runway and Blackness

Bree Runway is no stranger to racially-based assumptions about genre. “Normalise calling Bree Runway a popstar”, she tweeted last month, indicative of an industry that refuses to allow pop and blackness to dwell together. Bree makes versatility her bitch, from a punk-rock supercharged track, twerk-impelling jingles and blistering rap melodies. A spinning wheel of wigs and an all-black dance crew, the pop it-girl unapologetically aims to keep her blackness at the core of it all. But, regardless of her huge cult following and her consistent bangers, she is othered from pop, often labelled as a rapper.

“I hate my artistry being reduced to one genre because the proof is in the pudding, there’s no way I can be called just a rap girl or an R&B sensation,” Bree tells gal-dem.

“There’s no way I can be called just a rap girl or an R&B sensation. I would say my brand is completely plastered in popstar goodness”

– Bree Runway

“I would say my brand is completely plastered in popstar goodness – it’s fashion, it’s drama, it’s wild hair, it’s constant reinvention and absolutely no limit in sound,” she continues, “I can pop up as anything at any time: a rapper, a gospel singer, a country singer, it’s literally everything wrapped in one. For ‘Little Nokia’ I wanted to dress like how the track sounded, that’s why it was important for me to swing into the frame with a mohawk – that for me says, ‘Boom! Here I am with another look you didn’t expect’, reinforcing that I can do anything and appear as a new version of myself at any time.”

We talk about the state of pop: “I want to see different faces at the forefront of pop, right at the top – black girls and black men, winning pop category awards and not being automatically thrown into rap and R&B categories.”

The freedom of white artists

The categorisation of black artists especially as rap and R&B is something that comes up a lot. Publicist and pop fanatic Mofe Sey tells me, “We are shoved into a box and anyone that dares to break out of it is either ridiculed, dismissed or told they won’t sell records.”

She continues, “Alternatively, they are successful but are put in the ‘urban’ or ‘rap’ category. Look at Lizzo – ‘Truth Hurts’ is an absolute pop banger, spending six weeks at No 1 on Billboard charts making her the first female rapper to achieve this.”

“Black people aren’t allowed to be mediocre, they either flop in pop or create pop music categorised as rap or urban and excel”

– Mofe Sey, music publicist

Earlier this year, Tyler, the Creator made the point that his ambitious record IGOR winning “best rap album” at the GRAMMYs was clearly coded: “Whenever, we and I mean guys that look like me, do anything that’s genre-bending or anything, they always put it in a rap or urban category,” he said at the time.

As Mofe says, “White pop artists are allowed to dip in and out of genres as they please without being compared to the greats within them, or ruining their chances of being seen as pop artists. Black people aren’t allowed to be mediocre, they either flop in pop or create pop music categorised as rap or urban and excel.”

In a recent article for VICE, Briana Younger touches on how “the prevailing narrative of modern pop music is that it’s simply R&B music made by white artists”. Look at someone like Justin Timberlake, who debuted his solo career with 2002’s, Justified. A collaboration with prestigious POC hip-hop and R&B producers The Neptunes and Timberland, the singer experimented with more traditional R&B practices. The cherry on top of selling the Timberlake spicy-white alter-ego was an outstretched “urban” segment of beatboxing and his ability to pronounce ‘Señorita’. The result was a Grammy-nominated album, winning Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. Some of Justin’s most praised work in pop lies on the work of POC. He is free to explore sounds, but still be celebrated as a pop star and as something of an R&B rarity in the same breath.

Whiteness and light-skinned POC

It feels like the industry delegitimizes pop if it’s not coming from a white face, but people like Charli XCX are exempt from this. Despite her Indian-Ugandan heritage, she is white-passing and therefore a stamp of approval that is so often untold for many South Asians in music.

It’s hard to ignore that some of pop’s best and most successful POC musicians are light-skinned. From icons like Mariah Carey to rising newcomers Mabel and Conan Gray, their light-skin tone remains a common denominator.

“It’s hard to ignore that some of pop’s best and most successful POC musicians are light-skinned”

Undoubtedly, this is not the only aspect that played a part in their success, but with the industry’s glorification of whiteness, their light-skin made them viable as pop artists, while dark-skinned musicians largely remain sidelined. Though, even with colourism, mixed-race singer Tinashe’s blackness is still managed as something that would “taint” the genre, hence her music is discounted as “rhythmic pop”.

The difficulty of breaking through

Even if POC artists are critically acclaimed, there’s still difficulty breaking through to the charts and getting radio play. British-Japanese singer Rina Sawayama’s album Sawayama proves her to be a pop scholar. Sawayama plays like an encyclopaedic cocktail of 2000s pop music highlights as she rips into nu-metal production and tumble turns with glossy melodies. She also explores her mixed heritage, singing in both English and Japanese. A well-praised album in her back pocket, Rina still didn’t do especially well in the charts (Sawayama reached No 30 in the UK album downloads charts in April). She also found herself ineligible for The Brit Awards and The Mercury Prize, even though she has lived in the UK since she was four.

“Victoria Monét’s solo work has been reasonably respected, but it was when her words were carried by Ariana Grande that she was exalted with two Grammy Award nominations”

Chloe X Halle are also adored by critics, but their track ‘Do It’ reached just No 63 in the Billboard charts despite viral performances, a Tik Tok dance challenge and an entourage of Twitter’s favourite rappers behind it. Meanwhile, the sisters have thrived in predominantly less white spaces – the same track peaked at No 4 on Billboard’s R&B Streaming Songs chart in September.

Between ‘thank u, next’ and ‘7 rings’, Ariana Grande’s iconic songs have broken chart records. Victoria Monét, who penned both of Ariana’s pop psalms, shares that magic touch for witty, memorable punchlines on her own single ‘Jaguar’. Nonetheless, the singer’s wizardry for creating instantly quotable pop hooks is largely only stamped as R&B. Her solo work has been reasonably respected, but it was when her words were carried by a white woman that she was exalted with two Grammy Award nominations.

Like Tayla Parx, Kamille and many others, black women especially are largely unknown as names in their own right, hidden as excellent songwriters for huge (mainly white) popstars. Meanwhile, acclaimed singer/songwriter Sia is almost coddled for this very same thing, with a running joke about Beyoncé keeping her locked in a basement. Sia’s transition from songwriter for black musicians like Rihanna and Beyoncé to breakout soloist is treated as a celebratory moment in music.

“I think the main problem is that record labels and radio stations don’t know how to market black artists when they don’t easily fit into an ‘urban’ shaped box”

– Aron Walters, pop fan and 3D artist

Pop fan and 3D artist Aron Walters tells me it’s strange that there aren’t more mainstream black pop acts. “I follow so many black pop fans on Twitter, so it’s clear that there’s an audience,” he says. “The way that everyone seemed to rally behind Normani when she released ‘Motivation’ was so heartening. I think the main problem is that record labels and radio stations don’t know how to market black artists when they don’t easily fit into an ‘urban’ shaped box.”

Sexuality might also add another layer to this – there was speculation around MNEK’s debut album back in 2018 that it didn’t sell so well because both the industry and audience weren’t sure what to do with a Black, gay popstar. Instead, we see white LGBTQI+ artists in pop like Troye Sivan and Sam Smith prioritised. Thankfully, it feels like MNEK has been getting his flowers in 2020.

Celebrating a new future

In an entertainment industry manufactured to cater only to whiteness, there is a failure in how the system categorises artists. Too often, POC are disqualified from being classified as pop or sidelined because of perceived “foreignness”.

Senselessly searching for reasons to standardise music and uphold an outdated notion of what pop is or should be, ultimately fails POC. Issues of race and categorisation go beyond pop – we see it in indie, country and experimental, when those like Moses Sumney, Lil Nas X and FKA twigs are still caged as “urban”. The only outcome is to limit the creativity of POC artists, and cut short their reach and their bag.

Still, I am hopeful we’re witnessing a new era of our communities devouring pop music, leaving no crumbs for white mediocrity. It is something I feel very honoured to witness.