Photography by Laurence Ellis, Nahwand Jaff, Chameleon Visual

Priya Ahluwalia weaves her Indian-Nigerian heritage into her recycled menswear looks

We speak to one of London's most promising on-the-rise designers about her new book Jalebi and Southall's Punjab community.

Kemi Alemoru

16 Jul 2020

The last year has been overwhelming for Priya Ahluwalia. The London-based menswear designer has had her clothes snapped up by luxury sites like Matches and Browns and she was nominated for the prestigious LVMH prize. Then there are the little victories like being able to move into her own studio rather than creating from home. “It’s quite crazy, to be honest. It’s just been one thing after another. A whirlwind,” she explains over the phone.

If you’re impressed in what she’s achieved in two years you join the likes of other high-profile fans like notorious peng ting David Beckham who recently shouted out her new art book, Jalebi, via his Instagram story. Naturally, once we connected over the phone, it was the first question asked.

“I wouldn’t say we’re friends,” she laughs. “When I did a project with Adidas in Paris Fashion Week in 2019, it was me, Nicholas Daley and Paolina Russo. David Beckham was one of the ambassadors of the project. So it was after that that he sort of knows who I am. Maybe?” Despite the fact that Priya is being coy, he is definitely a fan. It is a big deal, and she is a big deal, even if she is still shocked by her success.

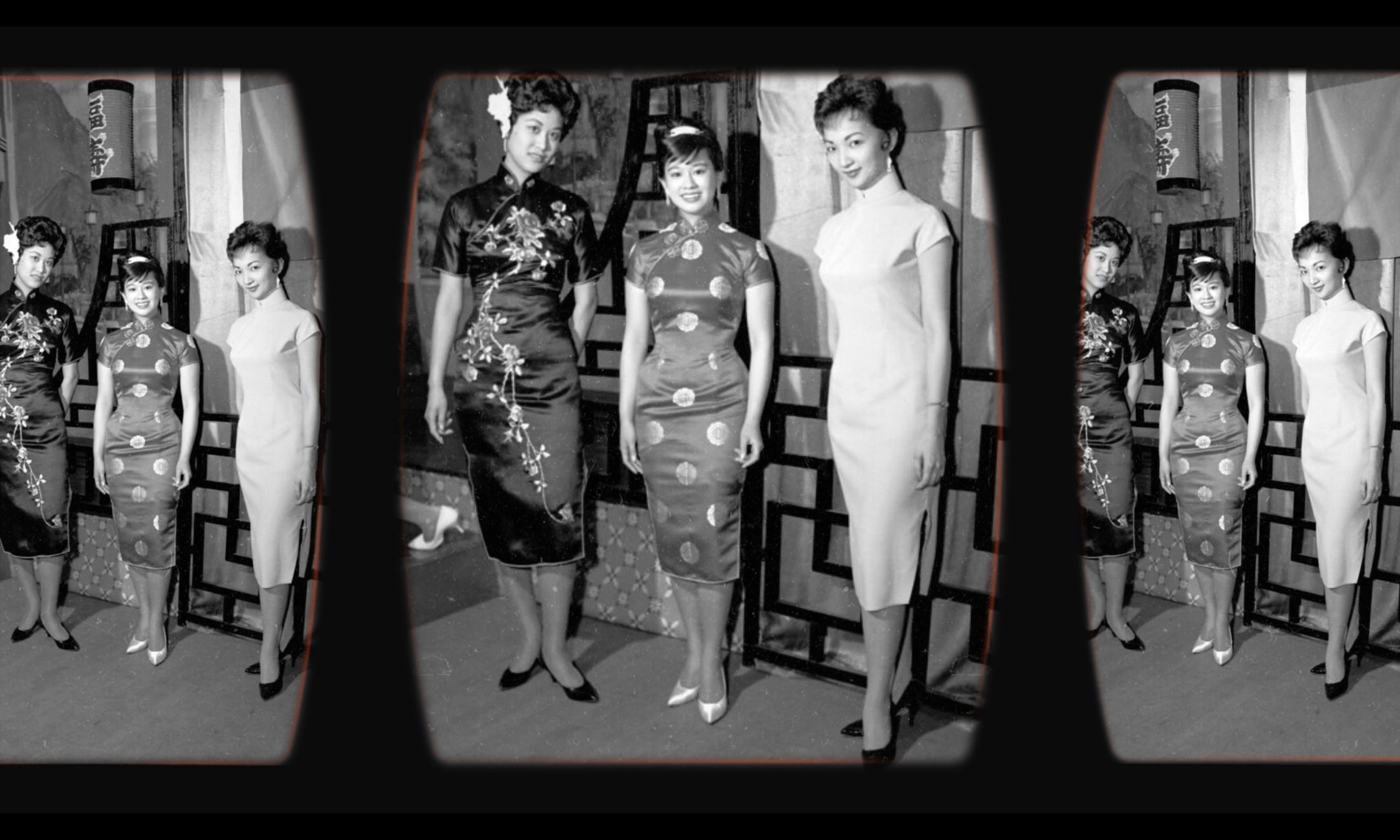

Priya’s eponymous brand, Ahluwalia, has become known for rich colour palettes and bold patterns, Indian tailoring, and flashes of Nigerian flair. She told Another Man that her recent SS20 collection imagines what her family may have worn to garage raves back in the day, while other pieces invoke the 1960s style of Asian, African and Caribbean migrants. Mostly her clothes are a patchwork of her passions. Piecing together sartorial markers from her mixed heritage (her mother is Indian while her father is Nigerian), they are made from recycled materials, an idea that was sparked on a trip to visit family in Nigeria when she was “trying to figure out who I was as a designer”. Among the unfamiliar hustle and bustle of West African roads came a more familiar sight. “I noticed all the guys in traffic jams were wearing second hand clothing,” she explains. Hand-me-downs from the West are a “huge business” as textile markets in Lagos, Ibadan, Enugu, Kano, Onitsha, and Port-Harcourt sell off high street, and sometimes designer goods, at affordable prices for locals. “I suppose that was the first time I really thought about where everything goes when we don’t use it anymore. Charities sell clothing to recyclers and countries around the world.”

She made it clear in our conversation, and in other interviews, that she’s keen not to be pigeonholed as “the sustainable designer”. For Priya, it’s a no-brainer as sustainability and recycling are naturally a part of her culture. She tells me that not being wasteful and being mindful of what you’re using are tenets of Indian and Nigerian households that had less wealth than British ones. “Don’t ask me why I’m doing it, ask the huge companies like ASOS why they’re not,” she quips, suggesting that all labels should be aiming to be more mindful on their impact on the planet. Her main goal is to create beautiful clothing that people actually want to buy. “If it’s not desirable then it becomes unsustainable anyway,” she adds.

As her brand is an ode to her roots it’s no surprise that her new book, Jalebi, turns the lens on Southall’s Punjab community, a place she knows well. Similar to her last book, Sweet Lassi, its named after childhood treats that remind her of family. Contrasting the old and new, the images include snapshots of the community as well as photos from family photo albums.

“Don’t ask me why I’m sustainable, ask the huge companies like ASOS why they’re not”

“[Southall] is Britain’s biggest Punjabi community – often it’s been said it’s the first. Punjab is a Northern Indian Territory. It’s a really specific part of India and Southall is geographically a very different bit of London,” Priya says. “It is culturally unique because it is a mixture of British iconography mixed with Punjabi culture that you wouldn’t see anywhere else in the world.” It aptly fits her mission statement as she continues to create a visual archive of her influences. There are hints of her own unique family history referenced throughout the book including conversations with her grandmother, a nod to those who’ve shaped her. “I haven’t seen any art books like it so it’s an opportunity to tell a new story,” she adds.

It was also sparked by the fact that a lot of Londoners have no idea what Southall is like. “My British friends had never been there before and didn’t even know about it but we live in the same city,” she says. This cultural disconnect doesn’t help counter the anti-immigrant rhetoric that is on the rise in Brexit Britain. “Right now there’s not a very nice atmosphere in terms of people thinking about immigration and integrated communities and I just thought it’d be nice to show it off.”

Due to coronavirus the photos cannot be displayed at a gallery and given the same IRL pomp and circumstance one would expect for such an ambitious project, so instead Priya launched a virtual exhibition. “I didn’t want to keep putting off the book launch until I could be in the same room as other human beings.” Working alongside Chameleon Visuals she created a realistic room where the photos adorned the walls with personal flourishes throughout: there are peeks of green space that you can see through the virtual gallery window. “That’s Southall park,” she clarifies.

Any second or third-generation child understands Priya’s trajectory of growing up in Britain and not feeling very attached to a “homeland” you haven’t visited. She explains how she used to speak Punjab but gave up on it as a teenager, as she began to hang around with friends more than her grandma. But then comes the learning process, cooking the food of your ancestors, trying to learn your mother tongue. This journey is present in Priya’s menswear collections which, while modern, are frequently looking back at another element of her upbringing or the lives of those around her.

Her brand represents a new era where authentic stories are told by the communities who were shut out from high fashion for decades. “Ten, 20 years ago it would have been a big Parisian house doing a collection about China. I think it’s quite nice now that there are voices that can tell nuanced and more in-depth stories rather than costume stories about heritage.”

No doubt Priya will continue to weave authentic tales of Britain and beyond via her ever-improving collections.