Cottonbro

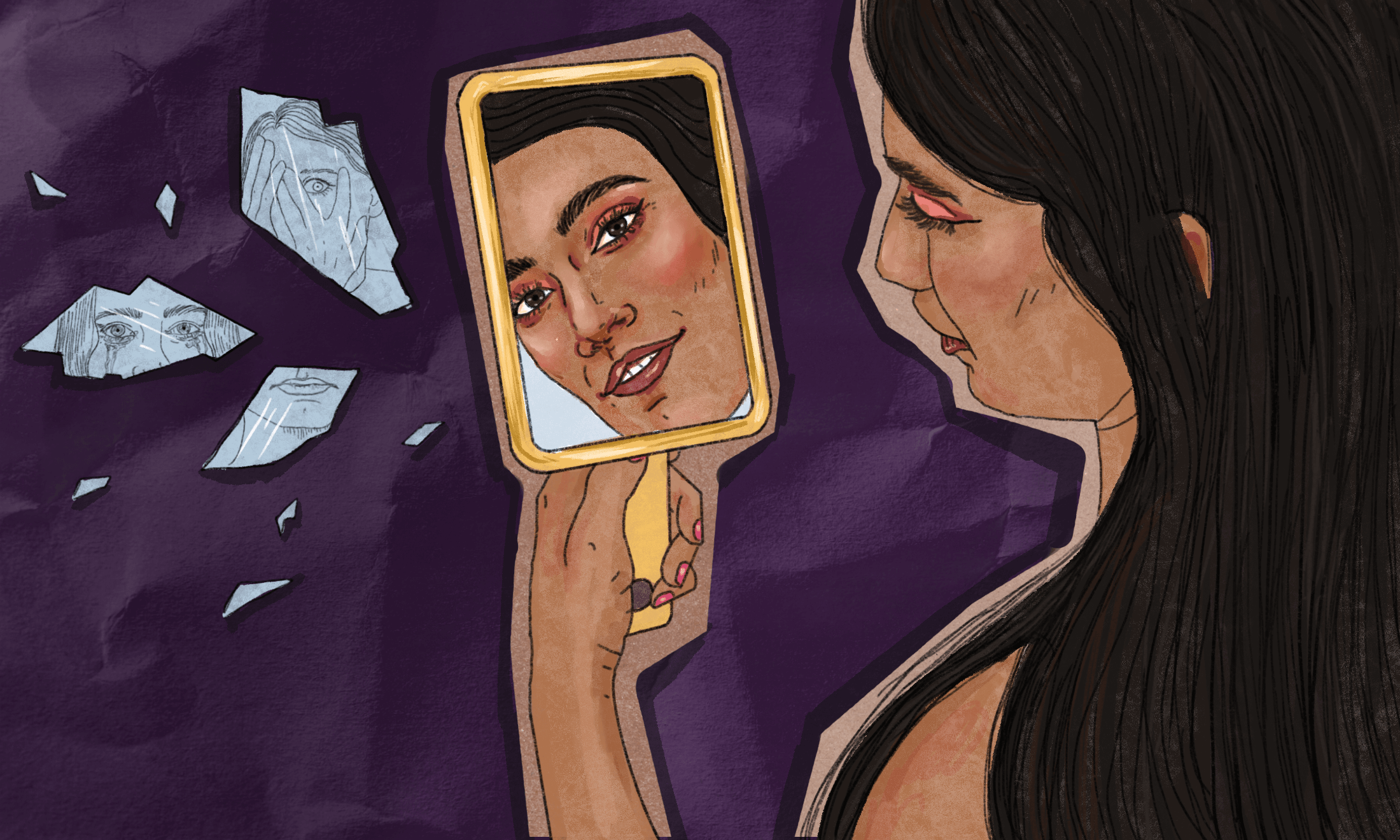

Stigma that self harm is just ‘attention seeking’ nearly stopped me from seeking help

This Self Harm Awareness Day, Yas Necati writes about the importance of destigmatising self harm.

Yas Necati and Editors

01 Mar 2021

Content warning: mention of self harm and suicide

At 19-years-old, I did something that makes me feel ashamed and upset when I think about it, even though it shouldn’t. I got dressed in front of a friend knowing there were fresh self harm injuries on my legs. For the first time in my life, I didn’t hide my wounds. I hoped she’d notice them.

It took me 13 years to get to the moment where I was able to share the realities of my self harming with a friend. I started self harming at the age of six using a less conventional method. As a child I couldn’t place why I did what I did. From the outside looking in, I was doing fine. I had a loving family, was quite the teacher’s pet, I loved to climb trees and I excelled at creative writing. But I had a secret, and I didn’t know why I had to keep it a secret, I just knew that I did. Even the GP was taken aback by how often I’d end up in his office, but I knew I couldn’t tell anyone, not even him.

I didn’t understand it as a kid, but I see now that my self harm was rooted in feeling othered. I knew I was non-binary and queer before I had the language for it or even understood properly what those things were. But other kids had language and their words made me feel like an anomaly. Every day of my life was about acting – but inside I felt this desperate want to run and escape from everyone and everything around me.

“I didn’t understand it as a kid, but I see now that my self harm was rooted in feeling othered”

The self harm continued into my secondary school years, but I began to find new and creative ways to do it. I would wear gloves to cover bruises, I would act ignorant at ongoing health concerns. A few reckless moments saw me in hospital and having to have three operations by the age of 16. Still, I never told anyone the injuries were caused on purpose. It scares me where my head must have been and the upset I put people who loved me through. I look back at young me with a lot of protectiveness. I wish I had better tools to cope with my internal and external battles.

I was still a few years away from being diagnosed with depression and anxiety. I would also go on to be treated for psychotic episodes as throughout my life I have seen and heard people and creatures that others don’t. Some of these presences held me and supported me. Others were malicious, aggressive and scary. During my school years, I felt like I was being stalked and hunted every night before I slept. My poor mental health coupled with the sleeplessness and feeling so isolated exacerbated the self harm.

I began injuring myself in a way I understood to be ‘self harm’ at the age of 17, because this was the only type of self harm I’d ever heard of before. I went to a very competitive college and it was here that things really became scary because I stopped believing anything was real. My so called ‘delusions’ were getting scarier without anyone to share them with, I started believing all sorts of things about being hunted and chased for being a ‘glitch’ in the system and taking philosophy was fascinating but in my teetering mental state I took the grand ideas about existence way too seriously.

“What I needed was someone to take me seriously and treat me like a person”

“I think, therefore I am,” wasn’t convincing enough for me – I couldn’t prove to myself I was real, so I struggled to see the point in anything. I almost ended my life then. A really good friend took me to the NHS child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) and I’m so grateful she did. But the psychologist and psychiatrist didn’t help – I felt patronised by them, particularly one, who was an upper-class white woman who I felt had no clue about my life or experiences. At the time I felt she treated me as if I was just a silly kid who was a bit confused, as a subject and experiment. What I needed was someone to take me seriously and treat me like a person.

It took two more years until I got dressed in front of my friend. This was the only way I could honestly say how I was, it was impossible to put those actions into words. Long conversations followed with her and a few other friends. They had known I was ill for a while, but this time round the conversations were different, as I knew they would be. My self harm was a physical manifestation of just how bad things were – before I shared it, no one was really getting the extent I wasn’t coping. There was lots of crying and hugging and even just the act of telling made me feel less inclined to hurt myself. I didn’t have to hold the worst bits on my own anymore.

I’m trying to unlearn the feeling of shame that so often accompanies self harm. If self harm is what draws attention to all the hurt someone is navigating, then that should be taken seriously. If someone is harming themselves because they’re isolated, we should do what we can to help pull them out of that isolation. If someone feels the only way they can communicate is by bringing pain and injury to their bodies, then we need to support them to have other ways to communicate in a way that’s safer and kinder to themselves.

“My self harm was a physical manifestation of just how bad things were – before I shared it, no one was really getting the extent I wasn’t coping”

This notion that ‘attention seeking’ is inherently bad is not only untrue, but also damaging. In my case, asking for attention from others at that crisis moment most likely saved my life, but if I’d asked for help sooner I might have never gotten to a place where I wanted to end things, I might not still be a network of scars.

We all ‘attention seek’ in one way or another – whether it be telling jokes at a party or reading a poem we’ve written. As humans, we need to be validated. We need to share our experiences. Every time we approach someone new, we’re asking for them to notice and pay attention to us. When we tell our friends good news, we’re seeking their acknowledgement and to share a happy moment. It’s important we create spaces where we can share our difficult moments too. Yes, self harm can be about attention. But aren’t a lot of things? Why are we stigmatising people asking for support when they need it most?

As I’ve grown into a young adult, I’ve learned the power of sharing. I’ve learned coping mechanisms that make me smile rather than go numb. I’ve been blessed with friends who I feel I can always reach out to, before things get bad enough that I want to hurt myself, not afterwards. I’m still in the process of finding a therapist who can speak to the trauma of being a queer, trans and Turkish person. Whose grandparents fled a war and still stock up on tinned food in case of the next one. It’s been two years and one month since I injured myself, and a year and seven months since the last time I intentionally hurt myself. It was reaching out and asking for someone to pay attention that got me here.

If you need further support or information about self harm in the UK, find contact details of useful organisations here.

If you need someone to chat to, start up a web conversation with someone at Rethink charity.

If you feel at risk of or are thinking about suicide or self harm, contact the Samaritans now. You can phone free at any time of day or night on 116 123 or use any of the options described here. They are wonderful people and they want to help you.