Thalassemia and thirst: How I learned to love dating with a disability

How do you navigate hookups when you've spent your entire life hiding who you are?

Eshana Anand

14 Dec 2020

Illustration by Nadine Nour el Din

I felt my disability for the first time during a screening of Scarlet Road at film school. The documentary follows an Australian sex worker who specialises in servicing a specific clientele — people with disabilities. The film was nerve-wracking on multiple levels. I had grown up believing that my disability was merely an accessory to my life, but watching the film revealed my failure in fully acknowledging it. I was also exhausted with my façade of sexual disinterest, because of the lack of faith I bestowed on my body. In a world full of noise about acceptance and body positivity, I had nobody to share my sexuality with.

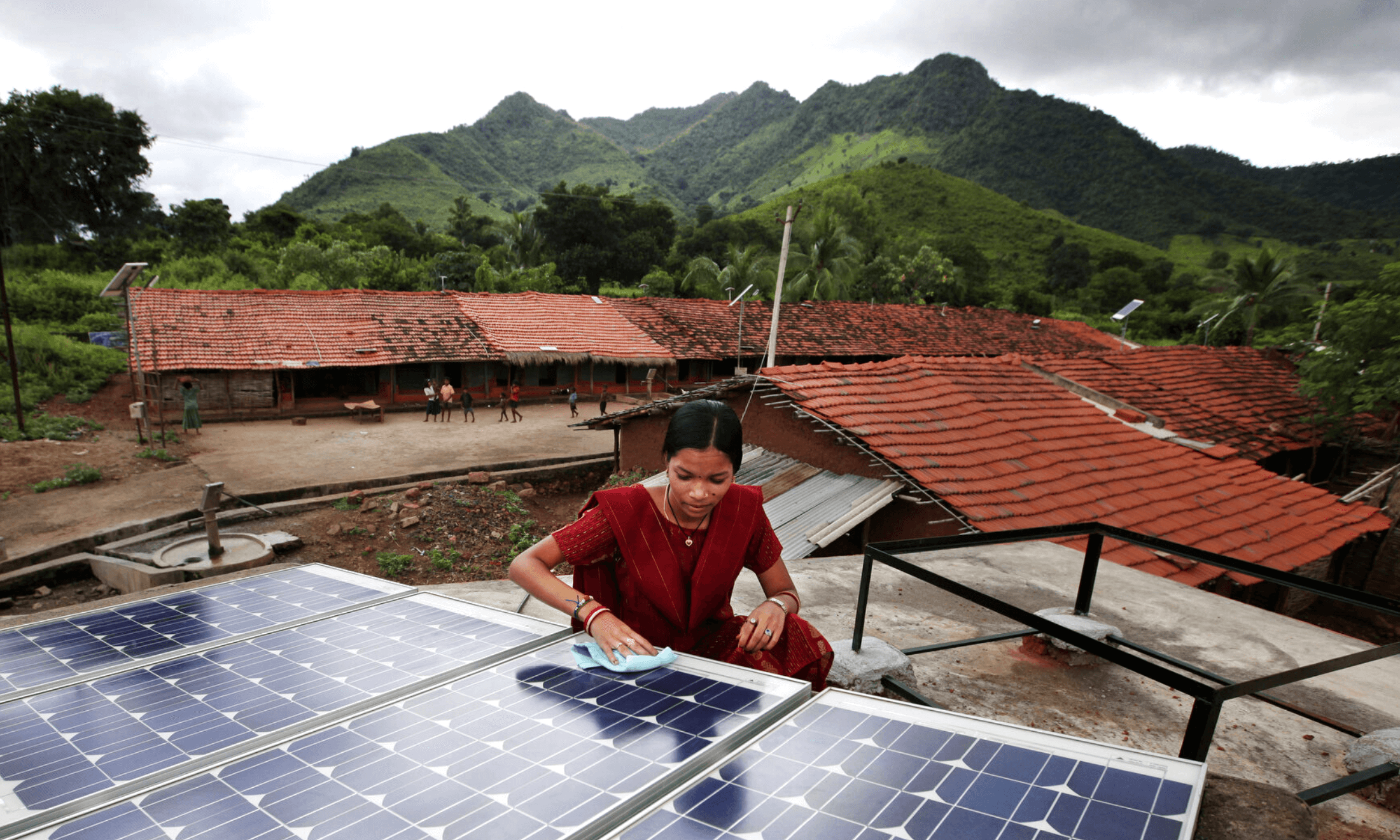

I was born with Beta Thalassemia, one of the many haemoglobin disorders that affect nearly 7% of the total world population, and I’m a carrier of Thalassemia Major, a genetic blood disorder prevalent among South Asians and Mediterranean people. My body doesn’t produce red blood cells (RBCs) and I rely on regular blood transfusions at the frequency of every two to three weeks for my survival. In addition, whatever RBCs are produced in my body are damaged and accumulate over time, which affects other organs and their functionality. The treatment for this is a combination of a life-long iron chelation therapy, in the form of oral and intravenous medications, which I have been on since I was six months old.

Growing up in 1990s India with a medical condition was not an easy ride. You were looked at with pity and denied equal opportunities; which was the case with me when my parents tried to get me into a school in Delhi. Having had an early glimpse of pity, my parents chose to conceal my health condition from then on, feeding everyone around us stories about my absence on treatment days, recurring every three weeks. One side effect of the treatment I couldn’t ignore was the scarring of my body. The intravenous injections piercing my body daily left wounds, which I carry to this day, damaging my self-worth.

“I was sexually repressed, struggling to navigate my sexual needs, which got lost in the chaos of dealing with my disability”

Through my teens and early twenties, I was sexually repressed, struggling to navigate my sexual needs, which got lost in the chaos of dealing with my disability. While people my age were checking off desires from their bucket list of young-adulthood, I was planning transfusions, juggling internships and managing my grades at university. Men around me assumed I was a snob who didn’t think anyone was good enough when the truth was far from it. I was shy and in need of a conversation about navigating my desires, which varied from cuddling to needing foreplay before having sex. Most of all, I wanted acceptance of my wounded body.

According to a 2011 WHO report, about 15% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability. In India, bar one film representing the life of a disabled activist’s life (Margarita with a Straw, 2014), there have been no attempts to address the sexual identities and needs of disabled people in the mainstream. You don’t see us on dating apps and most people don’t pause to think about our lives and needs, simply because we’re not visible.

My trauma had become cyclical. I was a ball of anxiety. Was I repressing my urges and needs just because I was certain of rejection the minute someone found out about my disability? Or, would someone reject me the minute they found out I had no prior sexual experience? I had to process these difficult questions, and somehow, I was all alone in addressing them. Expressing vulnerability meant losing any hope I had for getting laid with my agency intact.

I imagined conversation during foreplay having to go like, “Hey, I have a condition that makes my body disfigured and less desirable than yours. Now that I’ve said that out loud, can we bang?”

“There was no chat about the wounds, my body shape or even my skin, which is pale and indicative of things being wrong”

These chaotic thoughts lived rent-free in my head, until one day, I met someone on a dating app. He messaged: “World Cinema and chill?” As a filmmaker, I couldn’t resist the offer to re-watch my favourite Wong Kar-Wai. Ignoring the anxieties in my head, I skidded past the possibility of the date being a booty-call, which it was.

Still, I allowed myself to go with the flow; perhaps I wanted to take my agency into my own hands. It occurred to me later, as we lay in his bed, kissing and cuddling, how this was effortless – and also my first kiss, at 26, which he still does not know about. I shouldn’t kiss and tell, but to my credit, I was complimented heavily on my skills. There was no chat about the wounds, my body shape or even my skin, which is pale and indicative of things being wrong. Instead, we discussed politics and pop-culture as we cuddled.

My first hook-up, and the many that followed, made me realise that manoeuvring your disability and sexual inexperience can be unabashed, carefree and fun – if you trust your thirst and go easy on yourself. That hook-up was instrumental in understanding my body and sexual needs and my assertion about coming out to people if and when I deemed okay, a huge stigma that affects most people with invisible disabilities.

That one casual encounter changed everything for me and it’s become a hall of fame Ted Talk equivalent among my friends the same age as me, who also have little to no sexual experience. Since then, I have found a voice to discuss my sexual needs and desires and how I exercised them, normalising the conversation around casual sex and dating with a disability.

Talking and writing about sex and encounters has not only helped me gain confidence in owning my body and putting forth my needs in bed with partners, but also allowed a space for me and other sexually terrified and repressed people to exist and demand the same. I may not have actually watched Chungking Express with my hookup, but he definitely helped me create a better screenplay in my head.

The author’s name has been changed for anonymity.