‘The Other Windrush’: the hidden history of Afro-Chinese families in 1950s London

In this extract from 'The Other Windrush', writer Tao Leigh Goffe explores the history of relative Hyacinth Lee, who migrated to the UK from Jamaica.

Tao Leigh Goffe

30 Jun 2021

Tao Leigh Goffe/Canva

Family history is colonial history. How, then, to understand the vernacular photographic record and what is missing about the Windrush era, itself already an omission from British history? Since the inception of the technology of photography in the 1840s, the family photo album as an heirloom to be passed down, vertically, has formed the flesh of blood relation. The family album is also a literary surface inscribed with multiple meanings about race, gender, sexuality, class and who does not belong in the family tree. The visuality of collected images forms the fleshy proof of a seemingly biological argument for bourgeois belonging and familial intimacy. Blood is proof of kinship; the family portrait is flesh, and often colonial belonging.

Because family history is inevitably colonial history, I am invested in what and who is left out of the family album and outside of colonial history. Of particular (and selfish) interest to me is the impossibility of subjects of African and Chinese heritage. Photographs of Afro-Chinese families pose a challenge to the British colonial Trinidad experiment that wished to introduce Chinese labour to the Caribbean plantation to replace Africans in the early nineteenth century.

The ‘experiment’ documented in a secret Parliamentary Papers memorandum predicted the races would not mix. African and Asian people did, of course, ‘mix’; and many subsequent channels of migration were formed from Africa meeting Asia (both China and India) in the Caribbean. Where do we see these descendants present in the routes of the Windrush generation?

“The forgetting of Afro-Chinese histories, and furthermore of Afro-Chinese women, is an example of what it means to be beyond the interest or comprehension of coloniality”

Distancing myself from the binary of either a symptomatic or surface reading, I am invested in undoing the logic and violence of the colonial plantation, which is a logic of racial enclosure. How do photographs bear witness to my subjectivity as a British woman of African and Asian heritage who lives in the United States? It may not be intuitive, but the family album is a structure of racial enclosure too.

Ordered by the fictions of race and policing of class and colour, the sentimentality of the family album makes it seem innocent or objective. Its potential, though, for violence is epistemic in the knowledge it produces. And so, against the scripts of colonial nostalgia, I am most interested in the images that live as orphans beyond the family album. Taken as a visual argument and against the burden of proof of genealogy, I scratch the surface of colonial-era photography to grapple with how the stories told of another Windrush, of Afro-Chinese womanhood and other women of colour who are in conflict with the colonial historiography of the Americas. These routes bring me to the metropole London, the place of my birth, and where other women I will discuss have lived.

The forgetting of Afro-Chinese histories, and furthermore of Afro-Chinese women, is an example of what it means to be beyond the interest or comprehension of coloniality. I look to forgotten women, scratched out of history and the family tree, and the process of forgetting in the visual work of artists Albert Chong and Richard Fung. Their investigations interlace with my own queries into family albums and tracing my own story of Black Pacific and Chinese Atlantic crossings, being myself a migrant from the United Kingdom to the United States. Though I am a ‘new immigrant’ to the Western hemisphere, I have been here before, many times over. As an Afro-Chinese person, as a Black person, I am not afforded the immigrant’s amnesia to forget the violent institutions of racial slavery and racial indenture in whose wake people of African, Chinese and Indian descent live.

The plantation and suffering do not, of course, define the entirety of our lives, and yet the violent affective structure does define history. The plantation is a limit that determines why the photographs are missing for so many families, colonial subjects. The epistemic violence of erasing the histories of people of colour, a European colonial tactic, deliberately erased African and Asian people’s histories on those continents in order to more easily subjugate them. If we are lucky, we have a few scattered photographs that provide a visual clue to not only the faces of our ancestors, but potentially a more intimate understanding of the quotidian lives of our forebears. If not, we must hazard to engage, to imagine, in the conditional tense of possibility and speculation, about the centuries before and unnamed ancestors.

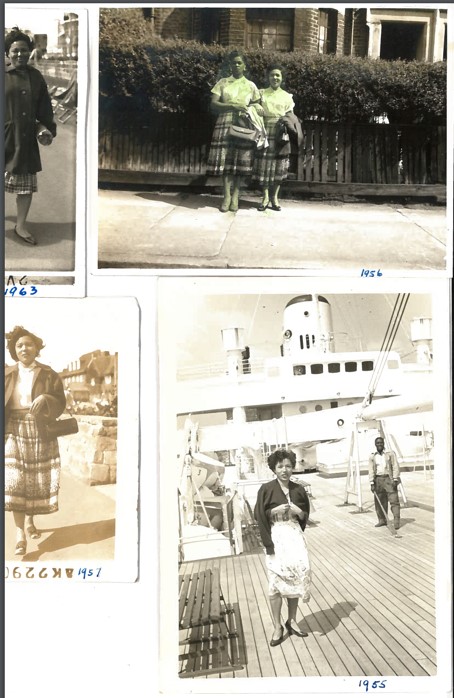

My mother encountered a set of photographs in Miami in April 2017 that raised many such questions for us. Her cousin, who she had then recently become reacquainted with after decades and formed a telephone friendship with, named Chris, emailed my mother scans of the archive of photographs of his aunts (her aunts). He had been the guardian of these pictures, in excess of an album, for many decades. My mother had never met this side of the family. Her father would not, or could not, speak of them or his mother. A bachelor without children of his own, Chris bestowed the archive of his Aunt Hyacinth to us, his cousins, whom he barely knew.

It is an inevitable fact that we are all descended from generations and generations of ‘hysteric’ women, diagnosed or not. By ‘hysteric’, I mean wandering, drawing from the dictionary definition and epigraph of this essay, women with displaced and dysfunctional uteruses who refused to conform to patriarchal norms, whether by choice or biology. I don’t know her, Hyacinth Lee, but she was one of these women.

This essay is an attempt to reckon with genealogies of hysteric women through family photography and the limits to what we can ever know for sure when someone has been scratched out of the family tree. I attempt to imagine Afro-Chinese women who were part of the shadow archive of the voyage of the Windrush from Jamaica to the UK.

My maternal grandfather did not know her either, his sister, Hyacinth. She, like so many optimistic West Indians, was part of an emergent class of labourers who migrated to the United Kingdom in the 1950s from Jamaica. Crossing the Atlantic, they became racialised as Black, whether they had been in the Caribbean or not.

My maternal grandfather made other transatlantic and trans-pacific journeys of racial formation from Hong Kong, where he grew up, to Jamaica, where he was born, to the United States, where he died. My research has so far been an attempt to illuminate the invisible circuitry of Black and Asian life beyond colonial circuits. I trace the lives of subjects across the British Empire by retracing Pacific and Atlantic Afro-Asian itineraries. So, I follow my grandfather and his siblings, of so-called ‘half relation’, born to Black mothers and Chinese fathers in Jamaica, to tell a full story of errantry.

The Chinese Atlantic is defined by the channels of what I describe as the institution of ‘racial indenture’, of the British trans-porting indentured Chinese and East Indian labourers to replace enslaved Africans on West Indian plantations. Subsequent to the failure of Chinese indentureship in Jamaica, a Chinese merchant and shopkeeper class from the same home villages in South China as the indentured labourers, travelled voluntarily to the Caribbean seeking entrepreneurial opportunity. These ventures were intended to be short-term, return trips, but investments were made and children were born, often to local women, Black women.

The discontinuity between the first wave of forced labour of indenture and the free merchant class that followed is an archival break, a gap that has not been accounted for. In both waves, it was mostly men who migrated, whether indentured labourers or merchants; they usually ended up staying in the Caribbean and fathering children. Edwin, my grandfather, and Hyacinth, his sister, were siblings, the result of these Afro-Chinese conjugal intimacies, living parallel lives across continents, born to Black mothers and Chinese fathers in Kingston, Jamaica.

I do not call the siblings ‘half ’ in relation because of the arithmetic of identity, of racial and genealogical fractions, performing a narrative of a biological essentialism I am not invested in. My mother did not know her Aunt Hyacinth, nor did she know her father’s mother – an Afro-Jamaican woman we believed for decades was Indo-Jamaican because it was what we had been told. Her name was Irene Caldwell, and as far as I know, my grandfather did not interact with his mother Irene upon his return to Jamaica in 1952, though she did not live far away from his home in Kingston, and he knew this. He had spent his life being raised by another mother, his Chinese stepmother, in Hong Kong’s New Territories during the Second Sino-Japanese War and Second World War. When my grandfather was alive, he would not, or perhaps could not, answer questions about that life of a Black boyhood spent in China. So I have been tracing his Black Pacific itinerary since his death.

The surfaces of Hyacinth’s photographs are literally scratched up. It is hard to tell if faces are scratched out or highlighted as if an honorific halo. The history of the Chinese in the Caribbean has been muted and is also one of mutilation. Flesh was mutilated by the whip, by the overseer, during racial indenture. While there is no photographic record, or visual evidence, we know this because of depositions of protest from the 1870s in Cuba.

“It was believed that Hyacinth died in the UK, and though she had a home, she appeared to be homeless. Word was sent to her mother in Jamaica about her mental decline”

Many Chinese across the Caribbean became fugitive and breached their indenture contracts, deserting plantations. The photographic emulsion, the light-sensitive colloid, comes in touch with a surface that then provides a burden of representation and racial proof. How, then, to join the discontinuity of multiple points of inflection in colonial history: Chinese indenture, Chinese merchant arrival to the Caribbean, and the Windrush? The photographs Chris gave us are a record of mid-century life that answered questions by showing us a life not often seen, of a Black woman in 1950s London.

Scratched, some faces are obscured. They appear almost colour-corrected or hand-tinted in a do-it-yourself fashion, with some faces being highlighted or coloured in, in red, yellow, green or blue. I do not know who did this to the photographs. Maybe it was Hyacinth when she looked back at these images depicting her British life. I only have scans of the photographs. So I draw what textural information I can from the materiality of the digital on computer screens. This is women’s history, scratched out, the ‘irresponsible reproducers’, as sociologist Dorothy Roberts poignantly described how the state imagined working Black women as a problem in late colonial Jamaica.

Hyacinth is much like the witchy women Silvia Frederici writes of, the reproductive source of labour-power, purposely erased from history because of a threat to the patriarchal capitalist order. Women, the means of production, are concealed. Mental illness is concealed. My mother knew not to ask further when her father said he had two fool-fool sisters, literally and derisively ‘idiots’, a catch-all for mental illness. Was this hereditary? What of the other sister? Was her name Lucille? It was believed that Hyacinth died in the UK, and though she had a home, she appeared to be homeless. Word was sent to her mother in Jamaica about her mental decline.

To periodise Hyacinth as entirely of the Windrush generation would be to slate her for the lazy casting of a Netflix period piece on postwar Britain. The Empire Windrush, her majesty’s transport, a vessel beckoned by the British Nationality Act of 1948, all at once defines the historical presence of Caribbean people in England and also forms other elisions and silences regarding race. The very question of the ‘Other Windrush’ is a question of who is pictured as being or looking Caribbean.

I heard Hyacinth was heartbroken. Perhaps she was like Stuart Hall’s heartbroken sister whom he writes of in his memoir. Hall’s sister faced electric shock treatment after a breakdown, having been barred from being in a romantic relationship with a darker-skinned Black man. Unwed too, did Hyacinth perhaps suffer such a heartbreak? Or perhaps it was the heartbreak that many colonial subjects who go to the metropole face, of colourism and racism, alienated as a Black woman in a foreign white land? But maybe Hyacinth became Black in England like Stuart Hall did. Like him, maybe she was brown in Jamaica, designating a non-Black identity of middle-class status.

Caribbean is not a race, and yet, as a demonym, it comes with many assumptions, especially from non-West Indians. Caribbean denotes an Indigeneity that is often ignored; it performs its own set of erasures and elisions. Amerindian people who still exist across the Caribbean are often casually erased as though a relic of the past. While the recognition in British history of the signifi-cance of the Empire Windrush is important to add to the colonial timeline, it is also just that, a pivotal point on a timeline of multiculturalist myth-making.

The fraught relationship between British nationalism and Caribbean subjecthood cannot be encapsulated by one voyage because there were many other Windrushes, before and after 1948. Other ships and timelines of colonial subjecthood and metropole homegoings of disobedient children, such as Hannah Lowe’s Ormonde (London: Hercules Editions, 2014), tell these stories: in Lowe’s case, the story of her Afro-Chinese Jamaican father’s arrival to the UK in 1947. Following the Ormonde, Lowe notes the arrival of the Almanzora the following year, also before the Windrush. Hazel Carby has written of her Afro-Jamaican father’s posting in the Royal Air Force before the Windrush in Imperial Intimacies (London: Verso, 2019). Many ships docked after 1948; are they any less important?

My father’s parents arrived on different ships sailing from Jamaica to London in 1954 and 1955, and met in the UK. The many itineraries of Black, Chinese and Indian subjectivity across time and space challenge convenient colonial timelines. I grew up in London and migrated to New York as a child, and my father gave me the classic text Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain by Peter Fryer to make sense of our transatlantic migrations and Black identity. Books such as these that reckon with Black presence in Roman occupied England and Black Liverpool show us that there are other ports of entry and temporalities of Black being in the British Isles.

My dad also taught me about the strategic essentialism of Black as a political identity that people of non-white origin, Africans, Afro-West Indians, Asian, and Middle Eastern people rallied under in Afro-Asian solidarity. Chinese and East Asian presence more broadly has always posed a challenge to the matrix of British racialisation. Caribbean Chinese presence or Jamaican Chinese presence is even more perplexing for the British order of race.

So to imagine Hyacinth, an Afro-Chinese woman from Jamaica in 1950s London, is to imagine the impossible. Some of her photos are stamped with the mark of the photo studio, “ROUGH PROOF PLEASE RETURN”. Did she pose for these photos at the now iconic Harry Jacobs studio where my father and his family posed for photos in Lambeth in the 1960s and 1970s? I do not know if Hyacinth returned to Jamaica. Hyacinth was rumoured to have checked into a sanatorium in London, but her fate is unknown.

This abridged extract was taken from The Other Windrush, edited by Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and David Dabydeen and published by Pluto Press. Available now.

For Christmas, Priti Patel is planning more devastating deportations – here’s how you can stop them

Read ‘Deporting Black Britons’ to understand the violence of Britain’s borders

Like so many victims of the Windrush scandal, Paulette Wilson died with a broken heart