Furmaan Ahmed

Tobi Kyeremateng’s theatre lovingly holds a mirror up to her community, but she shies from her own reflection

The founder of Black Ticket Project faces her fears in front of the camera and talks family life, body dysmorphia and her work's purpose.

Kemi Alemoru

09 Dec 2020

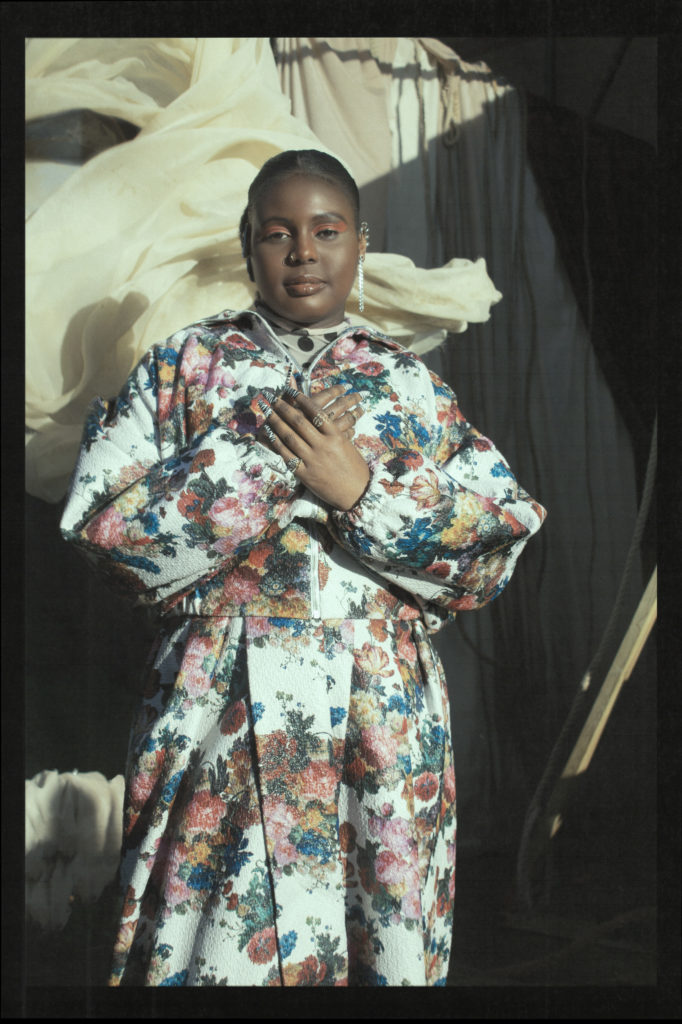

Tobi Kyeremateng is standing inside the purpose-built set outside her parents house in Tooting as the stylist positions her garment and the photographer readies their lens. With a click of the torch the spotlight is on her, her renaissance-like pose evoking patron saint of theatre realness. We’re used to seeing her play the role of orchestrator, rather than an illuminated protagonist.

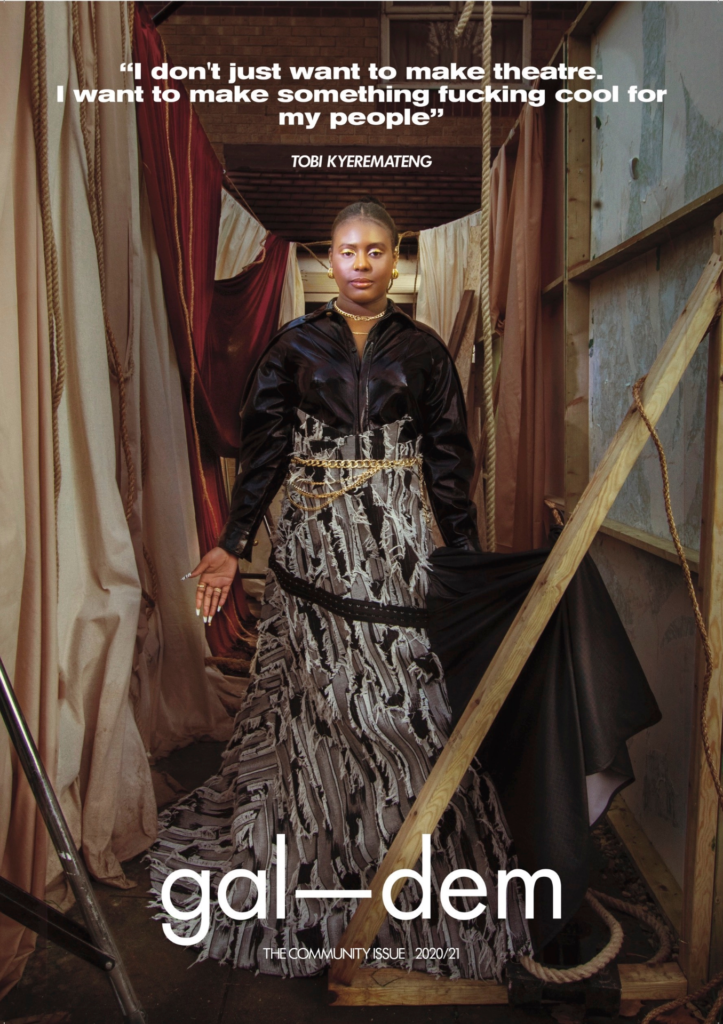

So far the 25-year-old has garnered praise for producing plays and live events, widening access to the theatre world via The Black Ticket Project, and spearheading projects with Tate Modern, the BBC, No Signal radio, and Afropunk. Despite being nominated as a trailblazer in a list curated by Meghan and Harry in the Evening Standard, being given the cover star treatment feels like a giant leap. “This is way out of my comfort zone,” she laughs. However, it’s completely fitting that someone with her CV would be chosen to front this issue. Tobi undoubtedly champions “community” and managed to do so in a year where connections could have been easily lost.

She grew up in south London as the firstborn in a household with three brothers and two girls. “I’m the oldest so the attention wasn’t really on me,” she says. Raised by her Ghanian father and Nigerian mother, storytelling was a part of family time. Her parents told lengthy tales of their own childhoods, their homelands. “I would say they’re artistic, even if they wouldn’t,” she explains. Tobi absorbed the expressive nature of her household by osmosis. Her house is a shrine to the family’s journey. “My parent’s house feels like a gallery, there are photos everywhere of every stage of their lives, of our lives. They’re so keen on documenting everything.”

“I remember at the end of my first production, seeing this black boy walk down the stairs with a bottle of JD in his hand and a spliff”

As a producer, her approach to the arts is refreshing because she’s not trying to honour thespian tradition and fit into that insular world, she’s honouring people and their own unique stories and cultures, in-keeping with her upbringing. “My thing isn’t ‘I want to make theatre’. It’s: I want to make something fucking cool in this space for my people. And how we do that it’s kind of up for grabs,” she says.

Tobi recounts how one of her first projects, creating a young people’s festival, was the moment she realised that making people feel welcome was as important as the contents of a production. “I just remember at the end of that night, seeing this black boy walk down the stairs with a bottle of JD in his hand and a spliff,” she says. “In my heart I thought: this is dope because you wouldn’t be in the space if you didn’t feel comfortable.”

Since then, she’s remained laser-focussed on demystifying theatre, developing projects that blend together music, urgent discourse and vital celebrations of the diaspora and its distinct cultures and experiences. “That word [theatre] holds so many colonial connotations to do with upper class-ness there’s a stiffness to it,” she explains. “It’s not explorative or imaginative, it has rules and if you don’t exist within those rules then you’re not allowed in the space. That was never my work.”

Tobi Kyeremateng wears floral pattern coat and short jacket by LalicA, dot pattern top and stocking, shoes by Foam of The Days, silver ear cuffs by B_dodi

Considering all the work she’s put in to make sure her community is reflected and revered, it’s ironic that Tobi finds it scary seeing herself celebrated front and centre. Last year she won Inspiration of the Year at Stylist’s Remarkable Women Awards and the photograph shot to publicise her, with its bright yellow and blues contrasting with Tobi’s megawatt smile, won a Portrait of Britain award. However, this didn’t do much to shift the perception of her own beauty. “I really hated that photo and I was really upset that it ended up winning because it was everywhere. It was in airports and shit,” she laughs before masterfully directing the conversation away from her as an individual. “The photographer was great, I really love the colours.”

Though her humility at times acts as a barrier to her believing in her own sauce, it’s something a lot of dark-skinned black women can relate to. In the past Tobi has been vocal about colourism and how Twitter gave the toxic prejudice a platform in her formative years, writing that misogynoiristic comments “would leave [her] feeling like a hostage in [her] own skin”. We’ve also spoken about beauty standards and how oppressive they feel in a gal-dem panel. Tobi reveals that this year she discovered that she has body dysmorphia and says she’s undergoing a “reckoning of sorts”.

“Lockdown has forced me to look at myself, my body and my hair in a different way,” she explains. “I feel like I should have a really snazzy answer about self acceptance but I can’t give that advice because I’m not really there. There are days when I feel like my face looks completely different to last week. I’m on Zooms and I’m looking at myself every day for eight hours and that brings up positives and other times I’m like ‘oh my forehead is really big’”.

“Lockdown has forced me to look at myself, my body and my hair in a different way”

Although she admits the ornate setting of a styled cover shoot “makes her feel sick”, it’s important for girls who look like her that don’t often get to see themselves as cover stars. In 2017, the 19 bestselling glossies published 210 covers, and only 20 featured a person of colour. When looking at publications like Vogue dark-skinned models have had very few covers historically.

For young people wanting to tread a similar path, her journey into production, live events, and writing was one shrouded in mystery. She says it’s atypical for anyone to express a love of the performing arts and not be pushed into being a performer. “I didn’t know this job existed until I did it,” she laughs. Throughout her youth she dabbled with the idea of being a radio host, a musician, a teacher, a garage MC. “I played around a lot,” she explains. “My secondary school let you learn instruments for free.” Around 2006 she took up the trombone, sax, violin (“for a few weeks and then I got really bored of it”), she was in a steel pan band for about five years and she even taught herself drums, before deciding that music wasn’t a “viable option”.

Her access to the arts is one that is recognisable for those that grew up on the tail end of a new Labour government that had pumped money into schools and arts funding. “So many more things existed back then. You appreciate things like that and Connexions [a government-backed teen support service that existed in the 00s] in retrospect,” she says.

Eventually she did a BTec in performing arts where a black teacher gifted her a copy of Random by playwright Debbie Tucker Green. “That was the first time I read a play or monologue that was performed by a black person and written by a black person. I was like ‘oh shit’.” She found an apprenticeship for Battersea Arts Centre and discovered all the behind the scenes work that goes into putting on plays and events.

While navigating these spaces she tweeted about her experiences and was “really really mouthy about everything that pissed me off” in the creative industries. She says: “Theatre is so insular so I felt like I was just talking to myself but I guess I was just a loud bashful black girl who just ended up in this sector. I just used to talk about everything – maybe to my detriment, I don’t know who I’m blacklisted by.”

Tobi Kyeremateng wears Black glossy shirt and denim deconstructed skirt by Jenn Lee, gold ear cuff by B_dodi, gold belt from stylist’s own archive

In 2016, Barbershop Chronicles by Inua Ellams debuted at the National Theatre. Set in Johannesburg, Harare, Kampala, Lagos, Accra and London it showed how the grooming space doubles up as a therapeutic for black men who check in with elders, role models, and friends. After viewing alongside a majority white audience, Tobi decided to buy 30 tickets for young black men to see the show. Thus Black Ticket Project was born.

Averse to taking sole credit, Tobi says: “It’s not just my thing, people wanted it. Someone else named it on Twitter, it was very ad-hoc and it will only be around as long as people find it useful.” Instead she prefers to see herself as the bridge between cultural institutions and other people doing work in the community. Similarly when Nine Night, a play paying homage to a Caribbean mourning tradition, was unveiled, Black Ticket Project crowdfunded £2,500 – filling 250 seats. That’s 250 young people who got to see themselves reflected and understand that their narratives matter.

“For me, half of any live event is about the other people that you’re with”

In the trash fire of 2020, Tobi has still worked to give black people a space to gather against all odds. During the summer, she produced an online festival entitled My White Best Friend which saw ten writers read out letters to say “the unsaid” which included touching letters from a trans man to his ex lover, or Afua Hirsch on living in “white Wimbledon” performed by the likes of Paapa Essieudu from I May Destroy You. It included DJs and post-show discussions as, for Tobi, the best thing about her line of work is sharing the experience with others, debriefing after the show by the bar or catching eyes with somebody as you both enjoy the scene.

“We’re not together so how do we make you feel like you’re still in a space experiencing things with other people?” she says explaining why they incorporated an after show discussion space. “For me, half of any live event is about the other people that you’re with.”

When you interview someone you can tell if they think the world revolves around them, or if they want to leave you with a grandiose impression of their intellect. But at many points of the interview, Tobi Kyeremateng moves the conversation away from her as an individual to the ecosystem in which her work sits. She sees herself part of a movement of people trying to shake up the industry rather than a one-woman show. Her work is teeming with empathy, which is why she has the power to truly transform theatre.

‘I want to make something fucking cool for my people’ – Tobi Kyeremateng’s theatre is all about you is the third release of gal-dem’s 2020 community covers. This year we’re saluting the people who have helped to foster, support, and build communities. You can support the gal-dem and purchase our beautiful cover prints here; they would make a great Christmas present!

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Photographer: Furmaan Ahmed

Set Designer: Ranya El-Refaey

Set Design Assistant: Hazel Low

Stylist: Innes Woo

Hair/MUA: Michelle Leandra

gal-dem producers: Kemi Alemoru, Bijal Shah and Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff