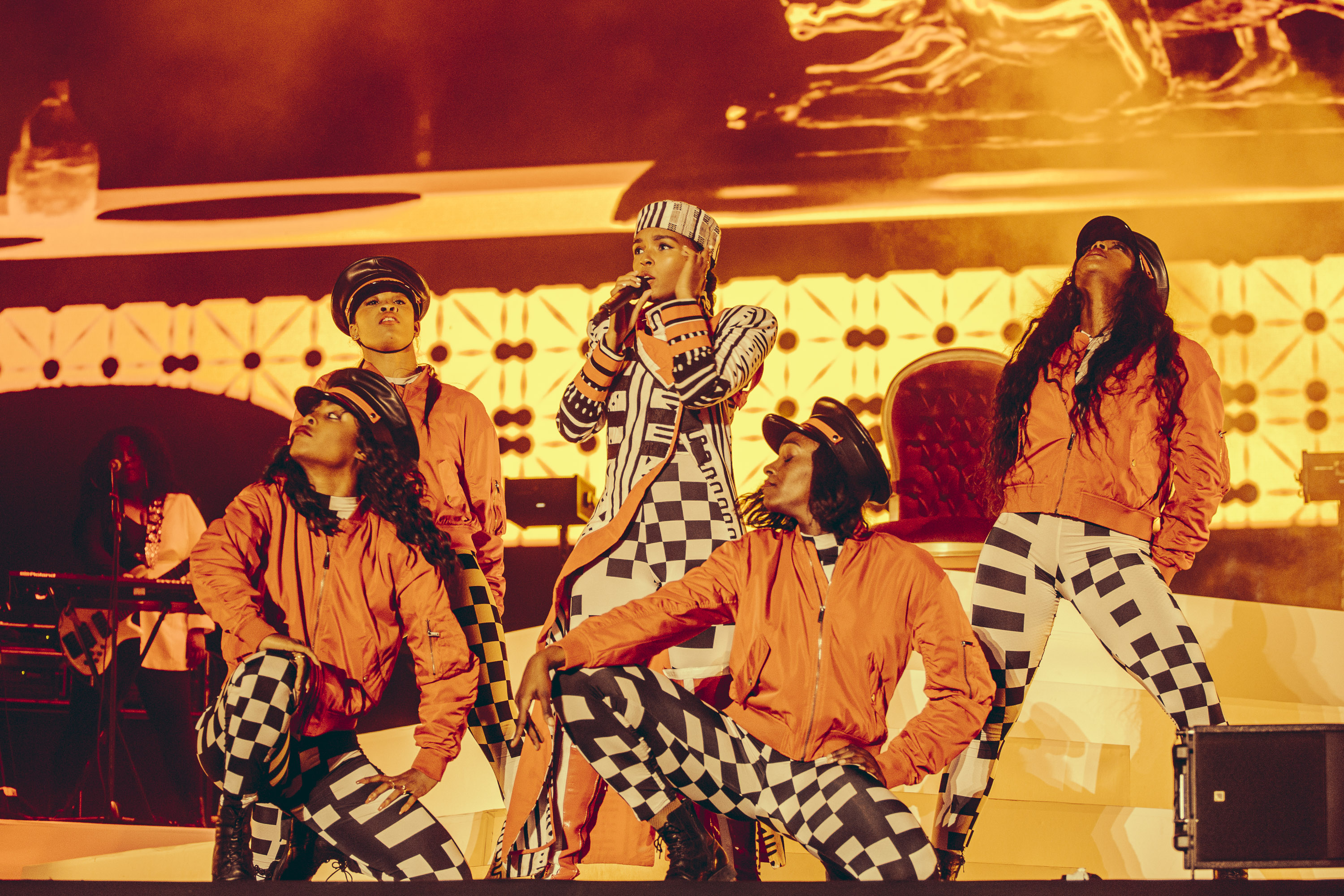

Photography by Tore Sætre

Why Solange Matters is a love letter to quirky black creatives

Bad Form's Reviews Editor dissects her book pick of the month, Stephanie Phillips' exploration of the trials and successes of a beloved musician

Morgan Cormack

25 May 2021

Solange’s reputation was undoubtedly catapulted into new heights with her third album, A Seat At The Table. Within Why Solange Matters, her authorial debut, Stephanie Phillips (of Big Joanie and Decolonise Fest fame) does a great job at zooming out and considering all aspects of Solange’s artistic journey to stardom, including her childhood.

From Tina Knowles putting a young Solange and Beyoncé into therapy together to alleviate any resentment to Solange’s turbulent relationship with her father, the writer expertly documents the artist’s life without it feeling like a monotonous biography. Rather, the chronology of Solange’s life is used to discuss issues in society and the arts, akin to how the musician’s art is used to dissect the human condition.

Stephanie’s first-hand experience as one of the only Black women in a predominantly white musical space allows her to write from a personal perspective that, undoubtedly, strengthens this book. The writer balances fundamental details with personal history and crucial context to detail why the “genre-traversing” musician is important to so many. Solange’s impact extends beyond music in the conversations she starts and how her meditative lyrics and interludes on A Seat At The Table managed to create a sense of powerful commonality.

Stephanie brilliantly fits in points about institutional racism, her own Jamaican family history and migration to Wolverhampton, her “search for belonging through punk” and “transformative Black ownership” within capitalism – all themes you don’t see coming on inspection of the book’s cover. Her writing forces us to see the wider picture, namely the inherent racial and gender biases that permeate the music industry.

There’s also a satisfying mirroring between her own experience and Solange’s. She juxtaposes the musician’s rise and the creation of cultural hub Saint Heron with her own journey in forming her riotous band Big Joanie and starting her own alt festival for punks of colour. She argues there was a transformative after-effect that impacted many Black women listening to Solange at the time: realising that “the seeds of our future lay in our hands”.

What listeners of Solange, and indeed people who haven’t read this book, probably aren’t aware of is how much she’s had to go through to be regarded with any real musical credibility. From the R&B genre confinement that plagues Black artists, and being told not to alienate white audiences, to her “traumatic” indie-scene experience. Solange has, for lack of a better term, really been through it.

Of course we’re taken on a journey through her sonic legacy: the echoing harmonies, melodic bass lines and sweet instrumentals. For example, of course we know ‘Rise’ is a brilliant album opener but Stephanie unpicks exactly why, likening it to a “semiguided meditation” of “repetitive lyrics and palliative tone” which gently pushes us into an album of raw narration around Black womanhood. Similarly, in the powerful interlude ‘Dad Was Mad’, Matthew Knowles recounts a vicious KKK swarm alongside “joyful bursts of piano”. It may seem oddly juxtaposing but Stephanie explains that the brighter backing track is to draw our attention closer to the story and to offer some optimism; “all is not lost”. Each song is explained with thoughtful detail but her discussions about music are done non-pretentiously. When reading, relistening to each track becomes vital just to listen out for the techniques she describes.

Much of this book may leave you with heightened emotions. In the chapter ‘Creating Community’, Stephanie explains how the Grammy-Award winning ‘Mad’ “reminds Black women that when anger is kept inside as a secret, it can fester, impacting your mental health and well-being.” She dissects the angry Black woman myth here but also cleverly roots it in reality; mentioning *that* elevator incident and the consequences of being Black and “visibly emotional”. Here, she considers Black women’s mental health, while also underlining Audre Lorde’s thinking around self-care for Black women as being “self-preservation” rather than a capitalist vehicle seized upon by the beauty industry. You wouldn’t think a book about Solange can go in so many directions without it feeling crowded. But Stephanie makes sure it never does.

This is the kind of book that will have you re-listening to Solange with renewed interest. It’ll also make you that overexcited friend with a lot of Solange-based trivia knowledge to hand. Although I’m both a music lover and Reviews Editor of Bad Form, artist specific non-fiction is not my go-to. I’ve always been wary that they often talk about the artist, rather than to them. But these thoughts didn’t cross my mind when reading Why Solange Matters. Not having access to Solange only allows Stephanie’s in-depth multimedia research to shine and for her writing to come from a place of personal passion, rather than the book reading like an interview.

Stephanie’s vibrant writing reminds us how Solange lit “the flame of creativity” within many Black women, reminding us that society’s expectations continue to be limiting. Long live “kooky” Black artistry.