via author

Cape Malay: a South African Muslim identity borne out of colonialism

Surviving slavery, colonialism and apartheid, this mixed-heritage Islamic community established a unique culture in South Africa.

Yaseen Kader and Editors

31 Aug 2021

Welcome to ‘Forgotten Diasporas’, gal-dem’s week-long series exploring histories of movement, survival and diasporic identity.

On the day of my grandfather’s funeral in Cape Town, I stood at the entrance to the kabristan (cemetery) with my family, as the caretaker nodded respectfully and said, “He was a good man, met die kudrat van Allah en die barakah van nabi Muhammad (sallallahu alaihi wasallam) [by the power of God and the blessings of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him)].” On an emotionally exhausting trip, visiting my extended family for the worst possible reason, it was hard not to smile. The trilingual sentence reminded me that there’s nowhere like the city I was born in.

While English was overwhelmingly the language spoken in my house when we moved to the UK, interjections of Afrikaans, Arabic, and Malay were often woven in so smoothly that it was difficult to tell them apart. It’s just how Cape Town Muslims talk. This hybridity has always been what’s defined the so-called Cape Malays. Under colonial rule – first Dutch and then British – they were a marginal group who forged an identity from a global patchwork of cultures. During the half-century of institutionalised racial segregation known as apartheid, they entered a hierarchy, positioned between white Europeans and the country’s disenfranchised black majority. But the government’s enforcement of racially-pure categories could never contain the true history of this community, and its diverse influences that shape it to this day.

Malay or Muslim?

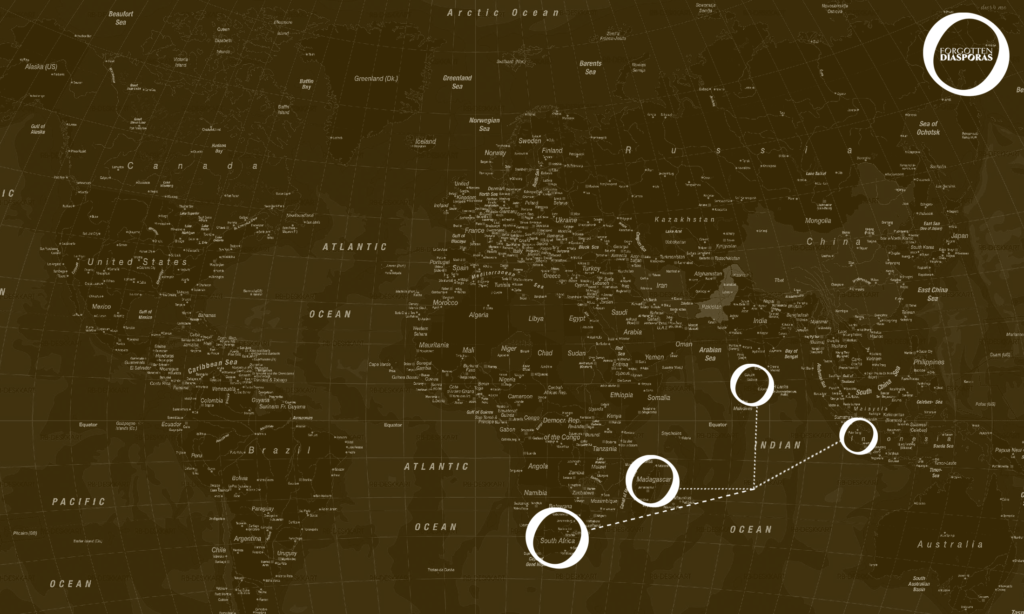

The Muslim community, sometimes called “Cape Malay”, descends from slaves, prisoners, and political exiles transported by the Dutch East India Company to the Western Cape of South Africa, which was declared a Dutch colony by Jan van Riebeeck in 1652. The workforce of the new Cape Colony was imported from Dutch holdings across India, Malaysia, and Indonesia, as well as mainland Africa and Madagascar.

So how did “Malay” come to define such a diverse group? It probably originally referred to the Malay language, which was spoken by several influential Islamic scholars and leaders, banished to the Cape for threatening to inspire revolution against the colonial powers in Indonesia. Exiles like Shayk Yusuf and Tuan Guru became figures of admiration among the slaves in South Africa – many of whom were Muslim in their homelands but prohibited from openly practising in the new colony by the Dutch powers. Through contact with slaves and prisoners, the scholars established the Cape’s Muslim community, with Malay as a unifying language of religious instruction. South Africa’s first mosque, Auwal Masjid, was founded in 1794 in central Cape Town’s Bo Kaap neighbourhood. With Tuan Guru as its imam, it welcomed enslaved and free worshippers. The Bo-Kaap is a Cape Muslim neighbourhood to this day, with its pastel-coloured houses making it one of the most iconic areas in Cape Town.

By the time slavery was abolished in 1834 – the Cape Colony now under British control – Cape Town’s 3,000 Muslims were a mixed-race group descended not only from African and Asian slaves but also the indigenous Khoi and European settlers. The religious minority – around 3% of the city’s population – was by now widely known as “Malays” to differentiate them from the much larger mixed-race Christian population.

“The Muslim community, sometimes called “Cape Malay”, descends from slaves, prisoners, and political exiles transported by the Dutch East India Company to the Western Cape of South Africa”

The term is still used both outside and within the community, where many see it as totally neutral. In 2021, “Cape Malay” adorns thousands of recipe books, tourist guides, and Instagram hashtags. Some have rejected it, however, given its use as a racial category under apartheid, dictating where a person could live and whom they could marry. From the 1970s, many politically-active Muslims favoured the term “Cape Muslim”.

For a younger generation growing up in post-apartheid South Africa, things are more nuanced. Cape Town-based filmmaker Amy Jeptha says she’s “embraced” and “decided to reclaim” the identity of Cape Malay, seeing it as “an acknowledgement of a history that [she doesn’t] wish to erase or forget”. Ameera Conrad, a director now living in London, notes that many in her family have dispensed with racial terms altogether, but for herself, she prefers “coloured” – a general term for people of mixed heritage in South Africa, which comes with its own baggage. Personally, I use “Cape Malay” interchangeably with “Cape Muslim”. It’s imprecise, yes, but I appreciate that it references the unique history of Islam in South Africa.

‘Ingemengde‘

When I ask Ameera what defines Cape Malay culture, the word she immediately reaches for is “ingemengde”. In Afrikaans, it means “mixed together”, like ingredients in a recipe. The fusion of influences is apparent in Cape Malay language, religion, and, unsurprisingly, food. Indian dishes like biryani, mutton curry, and the rose syrup drink falooda are all staples, while other recipes combine Asian and European flavours. Bredie is lamb, vegetable, and potato stew, spiced with cloves and allspice and served over rice. At Easter, the traditional food is fish – usually the local snoek – pickled in onions, vinegar, and spices for two days, fried and eaten with hot cross buns. Local legend says the fish in its bright yellow gravy (it’s the kind of food your tupperware will never let you forget you had) is an Asian twist on Dutch soured herring. The iconic sweet treat koesisters – potato donuts coated in spiced syrup and coconut flakes – are again a European base with a tropical finish.

Cape Malay Islam itself has also been described as syncretic: an amalgamation of different beliefs. The exiled Muslim leaders in the Cape were mostly Sufis, a highly devotional and somewhat mystical tendency within Islam. Dr Saarah Jappie writes that Sufism was “particularly appealing” to Muslim slaves dealing with a “hostile social environment”. The early imams also acted as dukuns – Indonesian faith healers who combine Islam with indigenous shamanism – providing talismans and herbal cures to slaves. Some Cape Muslim religious celebrations may have even more obscure origins, such as rampies, pouches filled with orange tree leaves which are soaked in rose water and given out on Mawlud, the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW). Historian Achmat Davids claimed rampies have “no Islamic base” and speculates that they actually derive from Hindu tradition.

Another example of this mixing is Afrikaans: the mother tongue of most mixed-race Christian and Muslim communities in the Cape. The language has always been a contentious issue. The 1976 Soweto uprising, in which police opened fire on unarmed black schoolchildren, killing at least 176 including 13-year-old Hector Pieterson, was sparked by the use of Afrikaans in schools. It was seen by many as a symbol of oppression, inexorably tied to white Afrikaner nationalism.

“We don’t speak a European language poorly; we speak, ‘the hybrid language we created’ ourselves, with hundreds of years of migration and cultural exchange flowing off our tongues”

In fact, Afrikaans originated as a creole: a simplified, hybrid language – in this case, 18th century Dutch reinterpreted by African and Asian slaves. Common Afrikaans words like “baie” (“very”), “baadjie” (“jacket”), and “piesang” (“banana”) derive from Malay. The Dutch in South Africa at the time mocked the developing tongue as “kombuitstaal” (“kitchen language”): the dialect of uneducated servants.

By the early 19th century, before Afrikaans had a standard spelling in the Latin alphabet, Cape Muslims were producing both religious and secular writing in the nascent language using Arabic script, including advertisements, student workbooks, and religious texts distributed by mosques. Chantelle De Kock, curator of the Afrikaans Language Museum in Paarl, says these Arabic writings are some of “the earliest written Afrikaans texts,” but tells me they have “remained largely out of the realm of formal education” about the history of Afrikaans in schools, adding that most visitors to the museum are surprised to learn of the influence of Asian and African sources on the language.

So in reality, the Arabic and Malay inflections that seem so specific to Cape Muslim Afrikaans were actually part of the language from the beginning. We don’t speak a European language poorly; we speak, as Amy puts it, “the hybrid language we created” ourselves, with hundreds of years of migration and cultural exchange flowing off our tongues.

‘To make South Africa a White man’s land‘

By the early 20th century, as South Africa’s white government was dispossessing the black population, so-called “coloureds”, which included Malays, were in a precarious position: working class, with limited education, generally living in rented or council housing (property requirements for voting consequently left most coloured people disenfranchised). My Malay grandmother remembers that most men in her community were joiners, plasterers, and bricklayers, while women often worked in the garment industry, either as machinists in factories or as seamstresses: the go-to for wedding or Eid dresses.

The government devised a “divide and rule” tactic to discourage solidarity between non-white communities: the 1920s saw efforts to define Malays as a distinct group from Christian “coloureds”. The reality was that Cape Town’s mixed-raced Christians and Muslims shared Afrikaans, pickled fish at Easter, and largely the same socioeconomic position. They lived together in the Bo-Kaap, while neighbourhoods like District Six, where my grandmother was born, also had Xhosa, Indian, and European Jewish families. But Malays were positioned by the government as a model minority: better than Christian coloureds because they didn’t drink or gamble; better than Indians because they’d been in the country longer.

This is where many who oppose the term “Malay” take issue. The government promoted the term in order to divide, while it promulgated a false narrative of a racially-pure population migrating from Malaysia, whitewashing the record of slavery, rebellion, and intermarriage. In a society obsessed with racial categorisation, Cape Muslims found themselves in the strange position of being constantly reminded of their ethnic otherness, while their actual history was being suppressed and rewritten before their eyes.

In 1948, the various racial laws that had existed in South Africa since colonialism were unified under a single banner of open white supremacist policy. Under apartheid, the infamous signs on public toilets, beaches, and benches designating them “NET BLANKES” – “Whites Only” were put up. The 1950 Population Registration Act created numbered categories for each racial group. “White”, “Black” and “Coloured” were capitalised in writing to indicate legal immutability, and membership to the groups was verified by “tests”. The inherent illogic of scientific racism was exposed during this process: my half-Malay, half-Gujarati paternal grandmother ticked all the boxes for “White” based on skin colour (paler than a brown paper bag) and hair texture (a pencil slid into her locks fell out when she shook her head).

“Suddenly uprooted, far from their work and mosques when many families didn’t own cars, she recalls that Malays in the 1960s largely remained apolitical”

“Malay” was declared a sub-set of “Coloured”, and given the number 02 (“White” was 00, while “Cape Coloured” was 01). Under the Group Areas Acts of the 1950s, black, Asian, and mixed-race people were forcibly evicted from their homes as areas were declared White; in the case of District Six, 60,000 people were moved out. In a final act of cruelty, the entire neighbourhood was bulldozed, nothing left standing except churches and mosques. It made plain the sentiment at the heart of apartheid legislation. The government didn’t want to move white people into the buildings of District Six; they didn’t think they were particularly nice buildings. Instead they levelled them, to show they could. To show people of colour that nothing belonged to them.

Coloured people were forced to resettle in newly-built townships like Manenberg, Mitchells Plain, and Bonteheuwel, where my mother was born. Suddenly uprooted, far from their work and mosques when many families didn’t own cars, she recalls that Malays in the 1960s largely remained apolitical: “we believed that if we prayed five times a day and we fasted nicely,…we were doing the right thing…. We did not see that anything in our identity as Muslims instructed us to look further.” Some did look further, though. Facing ambivalent religious leadership, Imam Abduallah Haron of Al Jaami’ah mosque connected with black activists in townships, recruiting for the banned Pan Africanist Congress. In May 1969, he was detained by the security services and held in solitary confinement until he died in custody with severe injuries; an inquest claimed he fell down a flight of stairs. His janazah (funeral) was attended by 40,000 mourners.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, a new generation of Muslims used their faith as the basis for political engagement, becoming one part of the national revolution fighting to dismantle apartheid. But a “Malay” identity had little use: many Muslims saw all racial labels as dehumanising, supporting the African National Congress stance of non-racialism. Others embraced the unity of non-white people espoused by the Black Consciousness Movement, whose leader Steve Biko wrote in 1971: “Being black is not a matter of pigmentation – being black is a reflection of a mental attitude”, encompassing all non-white people committed to the struggle. While political affiliations varied, the younger contingent of Muslims – Malay and Indian alike – were dissatisfied with the parochialism of many of their parents and were ready to march, boycott, organise, and face imprisonment in the service of justice for the country’s black majority and all other oppressed groups.

Cape Malays today

Today, like all groups formerly oppressed under apartheid, the 200,000 Cape Malays face challenges. While many coloured people still live in underdeveloped townships, the Bo-Kaap is ironically under threat of gentrification: the famous colourful houses are now coveted by students and professionals who are likely ignorant of the area’s significance to Cape Town’s Muslims.

But many Muslim creatives are eager to bring the untold histories of their community to the fore. Thania Petersen, a descendent of Tuan Guru, is a multidisciplinary artist using fashion and photography to recreate her lineage from her royal, exiled ancestor. The Soni Art Studio is another example, producing Arabic calligraphy, including murals in Cape Town’s traditionally-Muslim neighbourhoods.

And in 2020, Amy Jeptha’s film Barakat was screened at festivals around the world. It’s the first Afrikaans-language movie about a Muslim family and while Amy was happy to showcase the film to international audiences who “had no idea this community existed”, she also stresses that “the film was made for us”. 45 seconds into the trailer, a character says “kan ek net my moment enjoy, kanala? (can I not enjoy my moment, please?)”. It’s a trilingual sentence – Afrikaans, English, and Malay – the kind I’ve been hearing all my life. While Cape Malay culture may be too diverse and complex to label as one thing, I can say for sure what it sounds like. And it sounds like home.