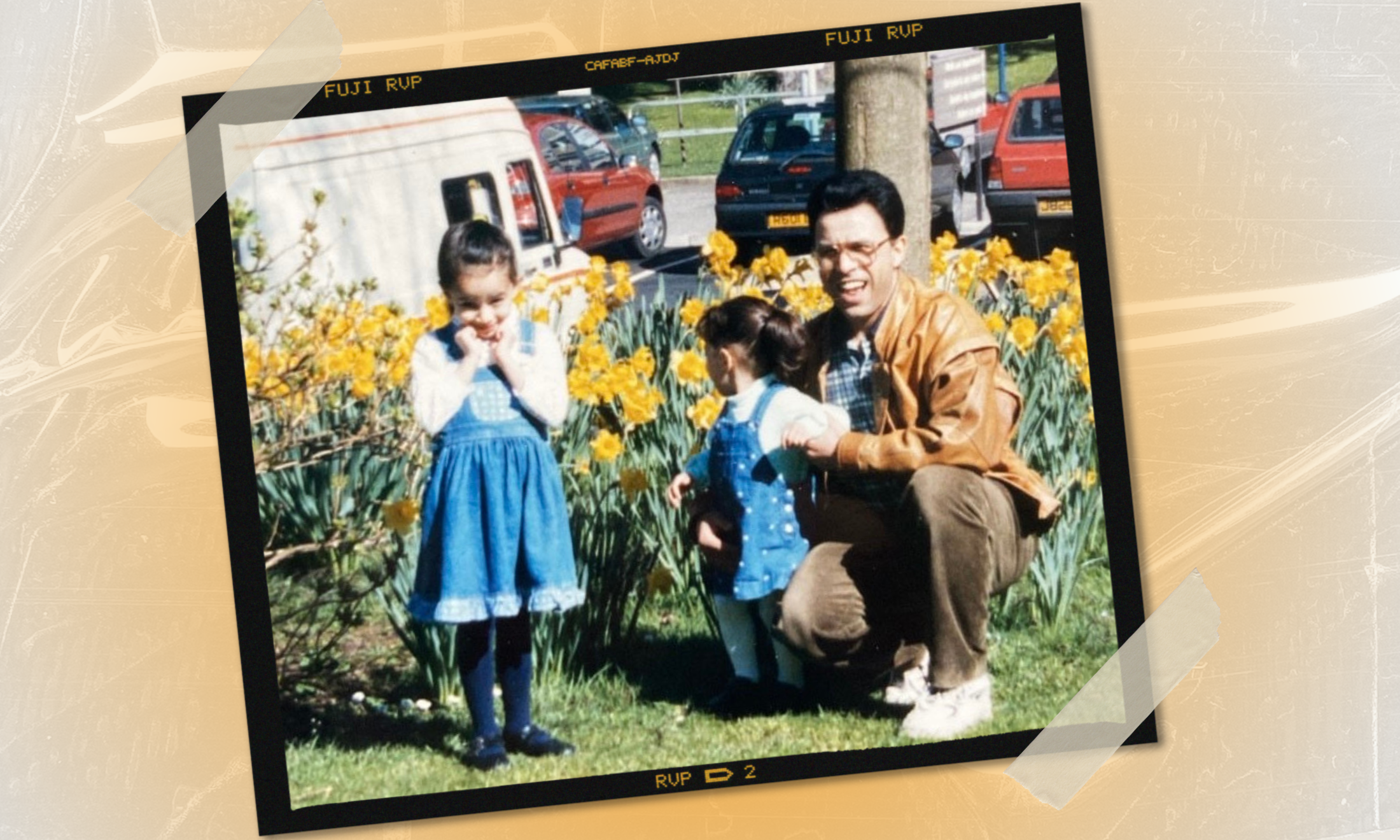

Heedayah Lockman

How I found my faith growing up within two religions

During my childhood, Islam and Christianity were two sides of the same coin. Then 9/11 happened and everything changed.

Laila Woozeer

20 Jul 2022

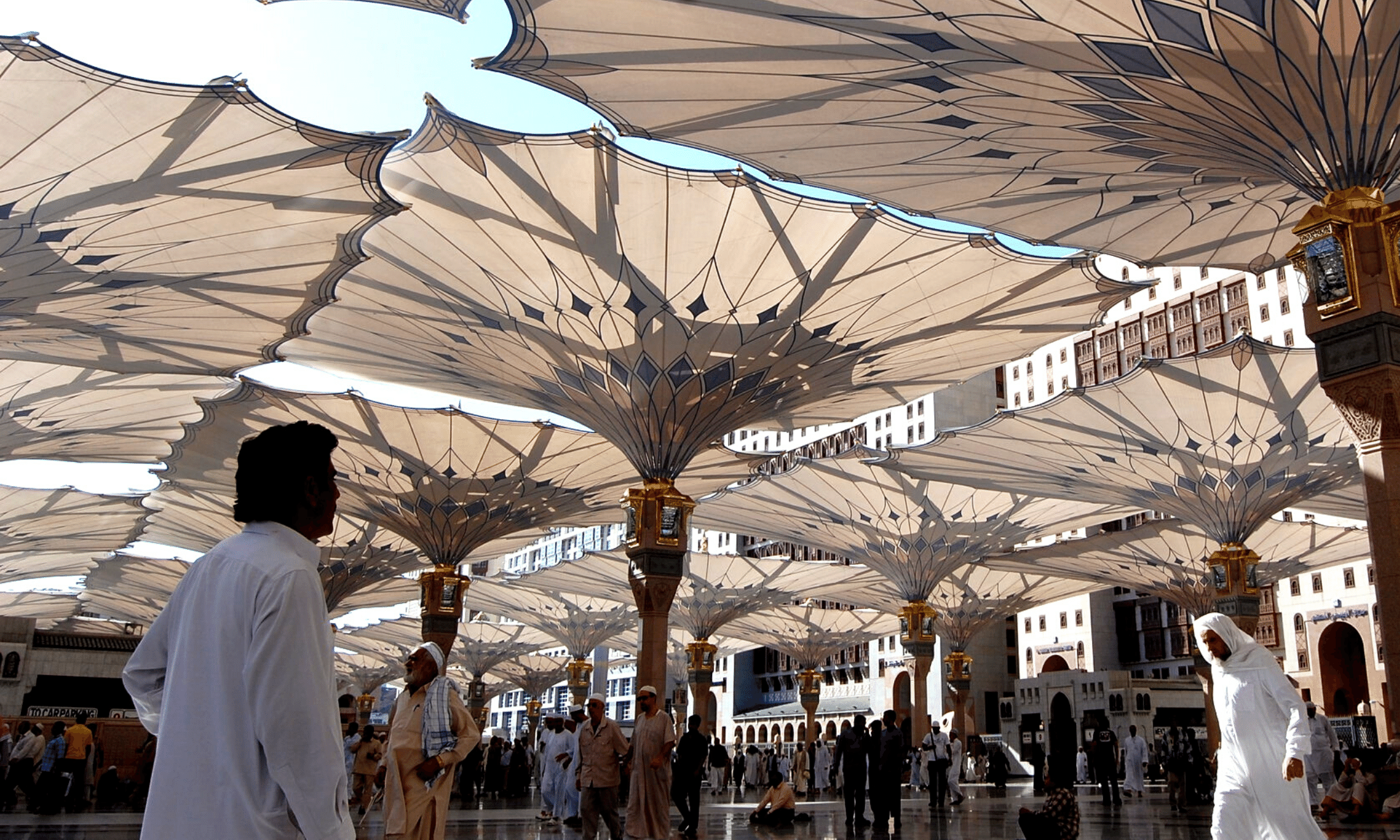

In Mauritius, the same things fit, just the other way round. As a small child, swapping cold Welsh mountains on one small, rainy island for Port Louis’s hot, dusty backstreets on a much sunnier island, ‘bread’ became ‘pain’ and ‘milk’ became ‘lait’. There were different versions of familiar things, like we didn’t go to Sainsbury’s on a Saturday morning to buy food; we went to the market in the early mornings before it got too hot. We didn’t eat fresh fruit after dinner, as a treat; we ate it in the morning, as a snack. And we didn’t sing along with Songs of Praise, like at my white grandparents’ house in the middle of Wales. Instead, at my Mauritian family’s house, somebody else sang and we listened and responded accordingly, answering the call to prayer that greeted us every morning.

Growing up between two families with different religions could have been confusing, but it made perfect sense to me in early childhood. Swap one small island for another and, of course, life is the same but flipped inside out. My white side worshipped God, attended Sunday morning church services and had a cross over the mantelpiece. My brown side praised Allah, listened to the sound of the muezzin played five times a day and had prayer mats facing Mecca.

“Growing up between two families with different religions could have been confusing, but it made perfect sense to me in early childhood”

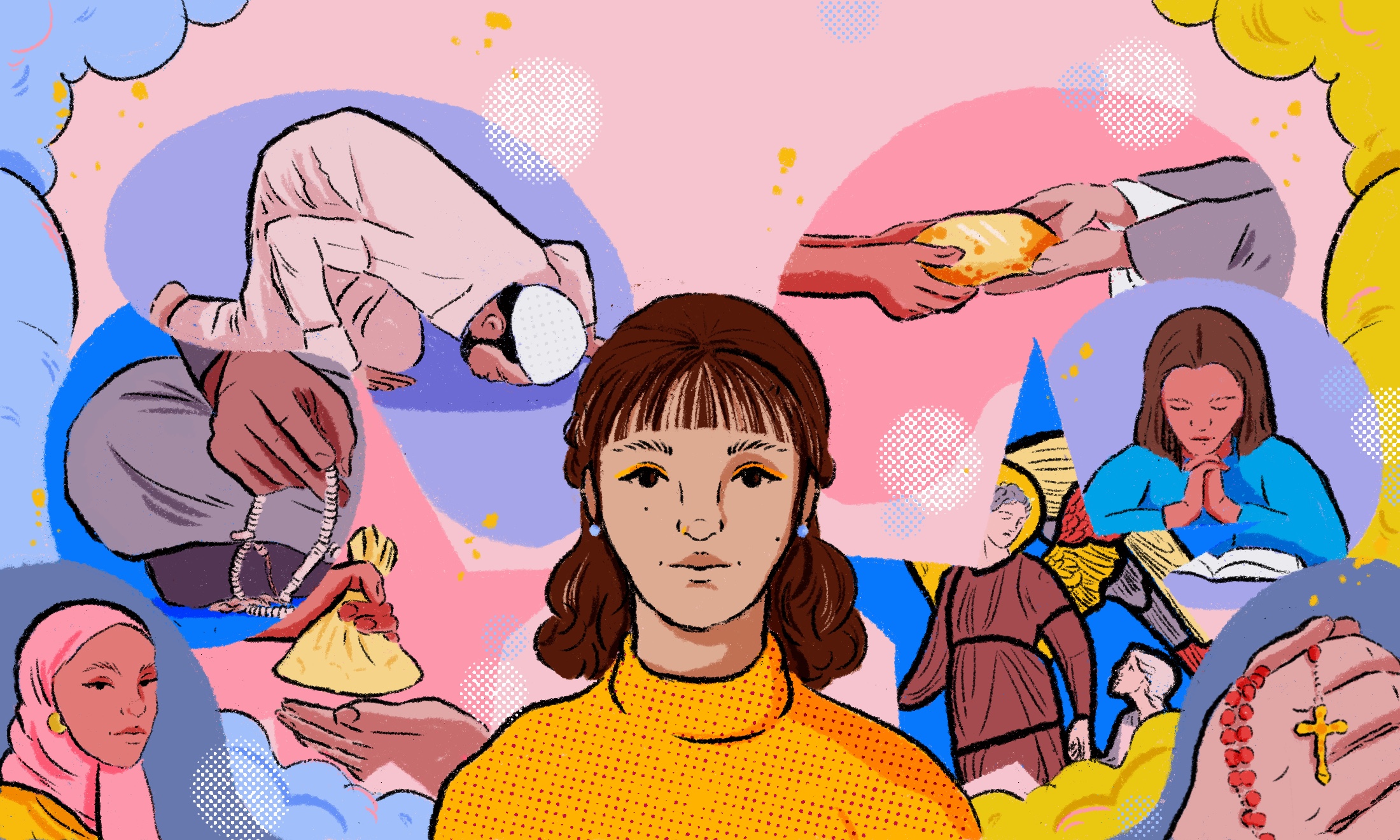

And so, that’s how it was for me, understanding Islam and Christianity as interchangeable. As an adult, it seems ridiculous to state that I genuinely believed two distinct religions were a variation of the same thing. But, in defence of my smaller self, there is a lot of crossover in both Muslim and Christian beliefs, especially if you are a confused young kid just receiving the most resounding messages from both. Be merciful. Be dutiful in your worship. Pray. Give to charity. Tell the truth. Be a good neighbour. Act in clear conscience. Be loyal to your one God. I think it is this last part that clinched it for me – be loyal to your one God. If there’s just one God, then we’re worshipping the same person in different places, right? We’re worshipping the one God, everyone’s been very clear about that. It was just another localised name change: bread and pain, milk and lait.

9/11 irrevocably changed that idea. I was 11 at the time of the attacks, and suddenly there was no doubt that not only was Islam extremely different to Christianity, but that it was wrong. In the aftermath of 9/11, Islamophobia became an openly discussed and accepted viewpoint in the UK, not just in mainstream media but affecting everything: politics, hate crimes and the internal bias of non-Muslim people.

As a child, I went from understanding these two belief systems to be fundamentally the same, to seeing one persecuted as the complete antithesis of the other. Even in my early teenage years, without a comprehensive understanding of either religion, it felt like the similarities in both were being willingly overlooked.

“I went from understanding Islam and Christianity to be fundamentally the same, to seeing one persecuted as the complete antithesis of the other”

Still, this shook me. How was it possible that something I had believed was one belief, was instead, not only two distinct religions, but apparently two distinct religions completely at odds with each other? Suddenly, I understood my simultaneous belief system was not only “wrong”, but that I couldn’t go on haphazardly accommodating both. I grappled with my understanding of how Christianity and Islam fit together – if they could, and if they should. Having been raised with both religions shaping my understanding of the world, it seemed bizarre to consciously ‘drop’ one, like willingly deciding to stop speaking a language or giving up a favourite activity. It’s hard to let things go when they have been there for so long.

It felt truer, and more helpful, to instead find a way for me to hold on to both my religious sides. Some links felt obvious; for example, Jesus appears in both Christianity and Islam, and both Abrahamic religions originate in the Middle East. Giving to charity and helping others are an implicit part of both faiths, and those ideals were also the ones most overtly on display in my otherwise fairly secular family home. Other developments in my understanding of my faith were influenced by my direct experiences of religion. I attended a strict Catholic secondary school which ultimately turned me away from organised Christianity. We studied the Bible in minute detail for GCSE exams, and daily school life involved participating in mass and feast days. None of that felt applicable to the way I had understood and practised faith in childhood, largely as a personal, private space in which I and my thoughts safely belonged.

“As a person with mixed heritage, my mind is primed to allow endless space for seemingly conflicting ideas, and for holding multitudes in the space of a single path”

Now, in adulthood, how I understand religion in many ways matches how I understand myself: existing as many things all at the same time. As a person with mixed heritage, my mind is primed to allow endless space for seemingly conflicting ideas, and for holding multitudes in the space of a single path. Understanding my identity in this way has led me to being able to understand everything else in my life that way, and so, though it seems like a fast track to damnation to say this, my faith follows a similar framework.

I feel able to honour both sides of my family and their religious beliefs in the way that I conduct my life, and in the practices I observe. The similarities in both religions’ principles feel clear to me, and I’m grateful for being raised with an understanding of both Islam and Christianity. Lessons from both religions have influenced me into becoming the person I am today; a person with a strong set of beliefs that goes beyond demarcated limitations, a person able to wholly connect to both sides of my family, and, most importantly, a person able to wholly worship in my faith.

Laila Woozeer is the author of Not Quite White, out now with Simon & Schuster.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.