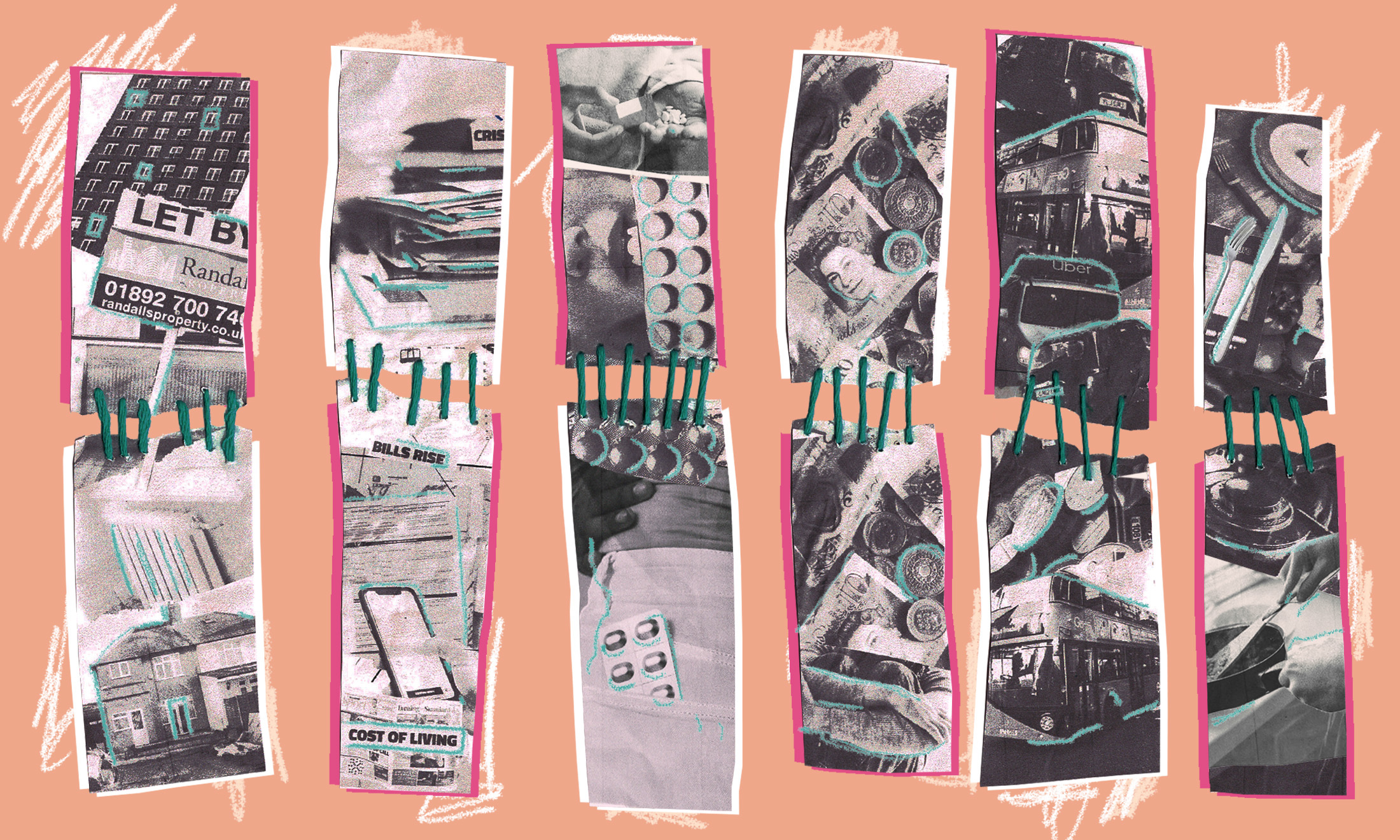

‘As disabled people we have been living in a cost of living crisis for years’

Rising costs in the UK are affecting disabled people of colour hardest and leaving many with no option but to cut back on medication, heating and other basic essentials.

Isabelle Jani-Friend

08 Nov 2022

Naomi Gennery

“It’s oppression on top of oppression, on top of oppression, and no one is trying to tackle it,” says Shani Dhanda, a disability specialist and entrepreneur.

Dhanda has osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), an inherited genetic bone disorder that is present at birth, also known as brittle bone disease. She is one of the millions of disabled people across the UK who are having to make life-changing decisions to get through the cost of living crisis.

“Disabled people have not been adequately supported for years and are now facing life-or-death situations,” she says.

Nearly half of the UK’s population who are living in poverty are either disabled themselves or living with a person who is disabled, and these households are already twice as likely to be struggling with the cost of living compared to non-disabled people. This is expected to worsen in the coming months, as research by disability equality charity Scope found that 91% of disabled respondents are worried about how they will afford their energy bills, with a further 45% stating that they are not planning on using heating at all this year.

As prices continue to rise, deprived communities are no longer making a choice between heating and eating. They are simply choosing neither.

“As disabled people we have been living in a cost of living crisis for years with these extra costs, as well as the years of austerity that we have faced under the Tories,” Dhanda tells gal-dem.

Since the Conservatives took power in 2010, austerity, cuts and the reform of the benefits system have plunged over a million disabled people into poverty, according to the Labour party.

Though there is very limited data about the impact the cost of living crisis is specifically having on disabled people of colour, it is evident that they are going to be facing the brunt of the emergency. Black and minority ethnic people are financially struggling with disproportionately high living costs and are 2.2 times more likely to be in deep poverty than their white counterparts, with Bangladeshi people over three times more likely, according to the Runnymede Trust, a race equality think tank. The research also found that while white families receive £454 less a year on average in cash benefits than a decade ago, this rises up to £806 less a year for Black and minority ethnic families, and up to £1,040 less for Black and minority ethnic women.

“Disabled people are now facing life-or-death situations in the cost of living crisis”

Shani Dhanda

Shivani* has just spent the last four months off sick from work and is now having to miss out on essential hospital appointments as she can no longer afford to attend them.

“I was born with a health condition that’s affected my entire life. I’ve had more surgeries and fractures than I can count. I’ve had chronic pain for 15 years, and I’ve been walking with crutches since I was 10 years old,” says Shivani, who has Type III OI as well as chronic pain. In winter, Shivani’s body gets even tighter and her pain increases due to the colder temperatures. Now, she’s having to think twice about having the heating on.

In order to manage her condition, Shivani has to have regular sessions with an osteopath to keep her mobile and to ensure her muscles don’t get too tight and painful. However, soon after returning to work, Shivani got severe pain in her neck and needed two emergency osteopathy appointments.

“That’s already £130 I didn’t account for this month,” she says. “Because of my condition, I don’t trust many people to touch my body, and my osteopath is one of the only people who can actually help me and not hurt me. But her prices are going up, so I’ve already had to cut back on the number of sessions that I have. These sessions help to build up my muscle strength, but I just can’t afford to have them regularly anymore.”

If she doesn’t have these regular sessions Shivani risks her muscles getting even tighter and her pain getting much worse, which is already starting to have a ‘domino effect’ on her body.

“All the progress I’ve made in my sessions has been undone as I’ve not been able to keep on top of it. So now my health is suffering, but I don’t have any other choice. It’s too expensive. I’m planning to prioritise things I need to do healthcare-wise and am cutting out all my self-care expenses.”

“Deprived communities are no longer making a choice between heating and eating. They are choosing neither”

Katouche Goll, a 25-year-old beauty content creator and disability activist with cerebral palsy, is also worried about the impact the rising costs are going to have on her social life.

“The biggest draw on my finances comes from mobility. I have to take taxis to get to work and to meet my friends, and if I want to go out and have a social life – like any other person in my demographic would – it costs money, but it costs me more money as a disabled person because public transport is very limiting and inaccessible,” she tells gal-dem.

“When my body gets tired and I’m in a lot of pain, I can’t risk exacerbating it, so I have no choice but to take taxis. The consequences of this inaccessibility and increasing costs will affect disabled people socially because if you don’t have the finances to travel, then you become withheld. And when disabled people are withheld from having a social life, it can have a very negative impact on our lives.”

“I don’t think it’s fair that we as disabled people have to pay more to live the same lives as everyone else,” Dhanda adds.

As a disabled woman of colour, Shivani says she finds it hard to know where some of the issues she faces come from. “In terms of pay levels, we know that white men are typically paid more than women, particularly women of colour,” she explains. “But are the problems I am facing because I am disabled, because I am a woman or because I am a person of colour?”

Disabled people are already almost twice as likely to be unemployed compared to non-disabled people in the UK. For those in employment, a study by People Like Us earlier this year found that people of colour could be being paid up to 16% less than white colleagues – so it’s not just disability that is having an impact on people’s finances.

“We face a disability pay gap so wide we work effectively two months of the year for free; the gap is wider if you’re a woman and a person of colour,” explains Dhanda. “And I tick all of those boxes. Disabled people of colour need help beyond the tokenistic £150 PIP (Personal Independence Payment) payment.”

Up to six million disabled people who claim disability benefits, including PIP (benefits for people with long-term physical or mental health conditions or disabilities), have either received or are expecting to receive a £150 one-off cost of living payment from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), but disabled people say this won’t help them cover their costs.

“This amount of money doesn’t begin to scratch the surface,” Dhanda says. “There are 14.6 million disabled people in the UK, and not all disabled people are on benefits, so using the benefits system to support disabled people is flawed. But for disabled people who are not in work, these welfare payments are their only income, and despite this, the government is still refusing to increase benefits in line with inflation.”

Until sufficient and proportionate help is provided, Dhanda is worried about how the crisis will continue to impact disabled lives. “We are facing a humanitarian crisis that is avoidable if the government provides urgent targeted support.”

*Names have been changed to protect anonymity

- For free advice on managing bills as well as finding out about any support available, Scope’s helpline is open Monday to Friday from 9am to 6pm and Saturday and Sunday, between 10am to 6pm.

- Scope’s Disability Energy Support provides free energy and water advice for disabled people.

- Mind has a list of helplines for mental health support, some of which operate 24/7 and offer support via email, text or online chat. Scope also offers assistance for managing mental health.

- Read gal-dem’s list of resources for support during this time, including where to find information on food banks and more.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.