Morokoth Fournier des Corats

Why the recent deaths of ESEA women in the UK feel so close to home

Overlooking the recent cases of Louise Kam and Mee Kuen Chong is a missed opportunity to humanise ESEA lives.

Suyin Haynes

11 Aug 2021

Content warning: descriptions of death.

On 21 July, a friend messaged me with a heads up to avoid social media because of upsetting news that had been circulating that day. With trepidation, I asked what had happened. “It’s another older ESEA lady that’s gone missing from the Bromley area,” she typed, referring to the woman’s East and South East Asian heritage.

My throat felt dry. 80-year-old Lucy Ho had been missing since that afternoon in Bromley, south-east London, where I live. I shared the news articles about her disappearance everywhere I could think of: on Instagram, Twitter and across several local Facebook community groups. In these groups, there was little reaction – a contrast to the usually lively complaints about that week’s late refuse collection or the latest uproar regarding different mask-wearing policies in shops.

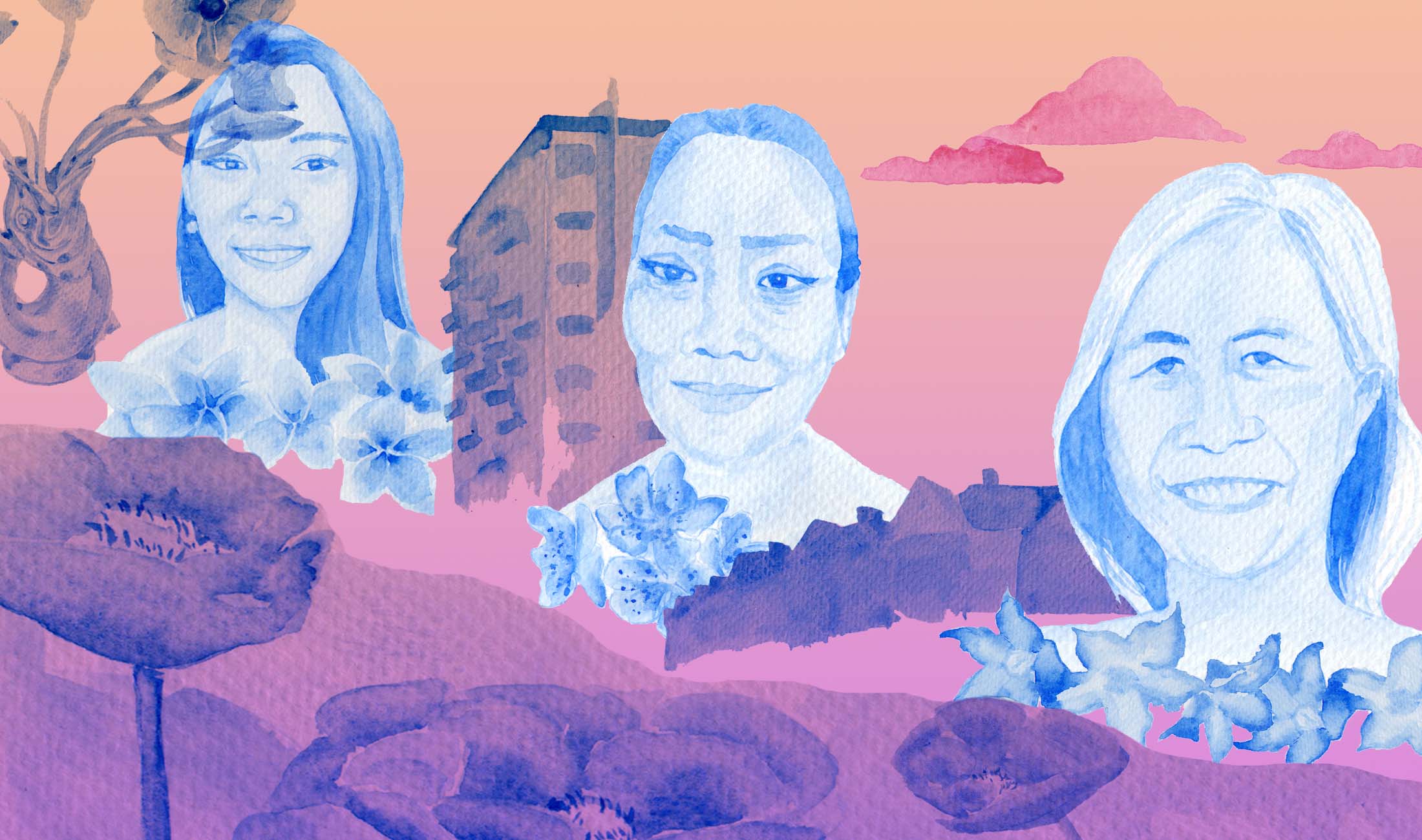

Luckily, police shared that Lucy was reported found and safe the next day. But Lucy’s brief disappearance brought back the memory of Mee Kuen Chong, and how not enough had been done to raise the alarm when she was reported missing from her home in London on 11 June. Originally from Malaysia, and known to her friends as Deborah, 67-year-old Mee Kuen had lived in Wembley for more than 30 years. Those who knew her have described her as a friendly, quiet, church-going woman. We currently know little else of her and her life, yet the way she was killed led headlines.

When I first saw Mee Kuen’s name circulating on my friends’ Instagram stories, it was in the context of her tragic death, not her status as a missing person. On 27 June, Mee Kuen’s body was found in Salcombe, South Devon, on the other side of the country. A woman has since been charged with her murder.

“When I first saw Mee Kuen’s name circulating on my friends’ Instagram stories, it was in the context of her tragic death, not her status as a missing person”

Now, police have found the body of a Chinese woman after her disappearance last month. Louise Kam, a 71-year-old mother of two was last seen at a shopping centre in north-west London on 26 July, with her family stating it was “entirely out of character” for her to disappear. A week later, two men were charged with her murder.

In Louise’s case too, it’s heartwrenching to know that I had only seen her name relating to the murder charges, rather than widespread attention immediately after she had gone missing. I found out about her case through seeing posts from ESEA friends on social media, provoking the familiar upsetting realisation that yet another life from the community had been taken, and yet again, there was little recognition beyond our circles.

And while comparing the cases of missing people does more to flatten any nuance and specificity than it does to draw focus to those who have not been as widely covered, it’s not lost on me that the disappearance of these two women, both of ESEA heritage, did not receive significant national media attention until after their deaths.

“Everyone I know has a story – whether it’s one of being racially abused in public, in the workplace, or feeling completely unseen, unheard or invalidated”

There’s been so little reporting, information, or even interest, into the lives of either woman that who they were has been compressed into the basic information from police statements. It’s yet another missed opportunity to humanise those in our communities facing injustices. Be it the disproportionate deaths of Filipino healthcare workers due to Covid-19 or the recent forced deportation flight targeting Vietnamese migrants, these issues are far too often underreported or entirely left out of national media narratives.

Police have not linked either Mee Kuen or Louise’s cases specifically or publicly to hate crime, nor categorised them as racially motivated. Yet that doesn’t make it any less painful to see the faces of these two older women of Malaysian and Chinese heritage, smiling in their police handout photographs. And in the context of the last year, which has seen a significant rise in Covid-19 related hate crimes targeting people of ESEA descent, the community here in the UK has already gone through so much heartache.

Everyone I know has a story, whether it’s one of being racially abused in public, in the workplace, or feeling completely unseen, unheard or invalidated. The lack of coverage around Mee Kuen and Louise’s stories evidences the erasure of ESEA experiences which runs through our lifetimes; in the recent 2021 census, the two most applicable options for those with heritage from the region were ‘Chinese’ or ‘Other Asian,’ showing how even through data collection, we are simplified and overlooked. The pandemic too has impacted local community centres and support services working with our elders, forcing these organisations to rely on crowdfunding efforts to remain open.

“We grieve for the loss of those we didn’t know personally, even though they may be miles and oceans away”

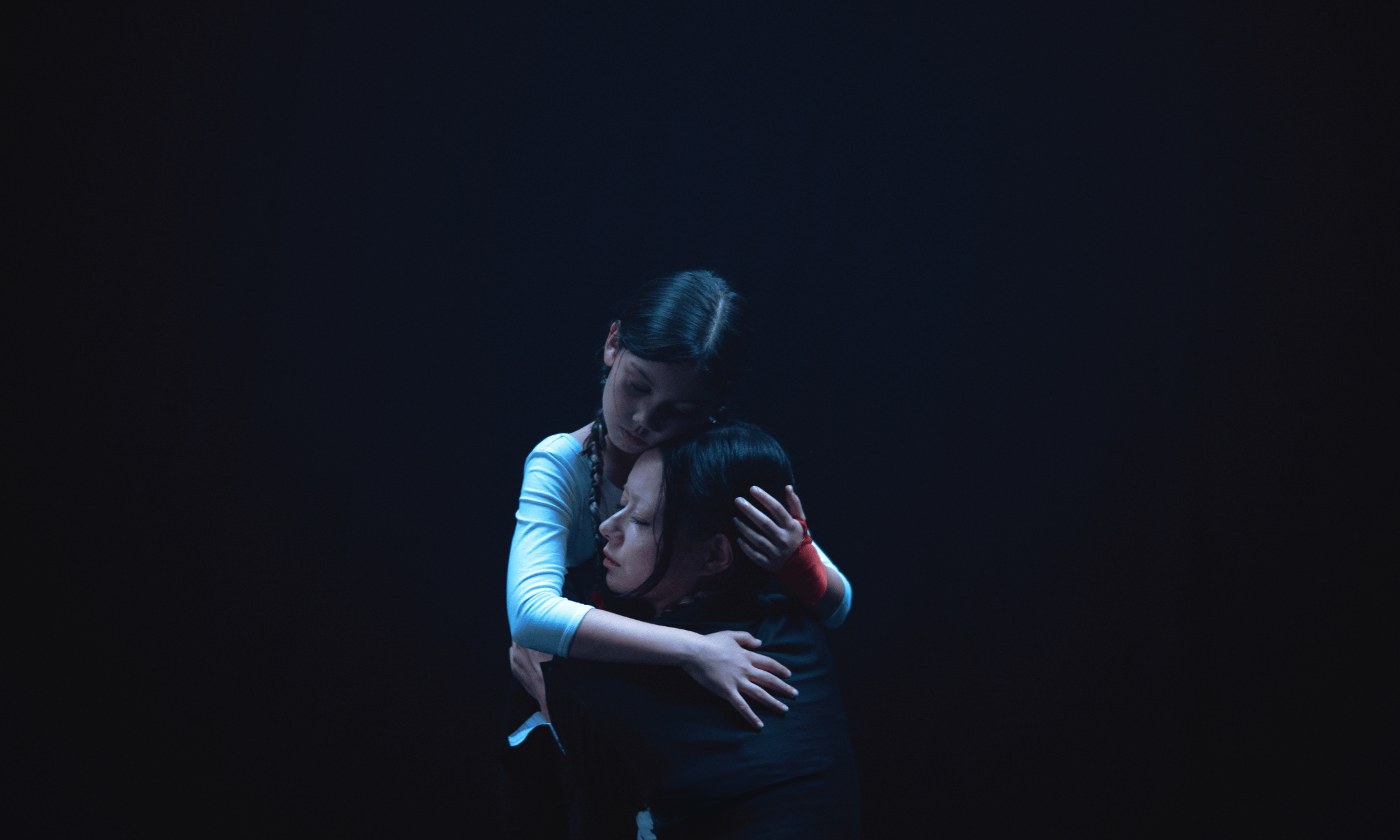

Grief is a messy myriad of emotions, often all held together at once. The fog of helplessness and paralysis; the fury at lingering questions you know you will never know the answer to; the frantic behaviour to control what you can, given the uncontrollable has already happened. We grieve for the loss of those we didn’t know personally, even though they may be miles and oceans away.

I will never know what full lives 25-year-old Bennylyn Burke and her daughter, Jellica, could have led, nor what happened in the events leading up to their murders in Dundee in March. I will never be able to suppress that feeling of anguish reading that the shooter who killed eight people, six of them women of Asian descent, at spas in Atlanta, Georgia, was excused as “having a bad day” that same month. I will never be able to stop the crack in my throat any time I see a police handout of a missing person like Lucy Ho, and feel desperately like I have to do something, anything, before the news cycle moves on.

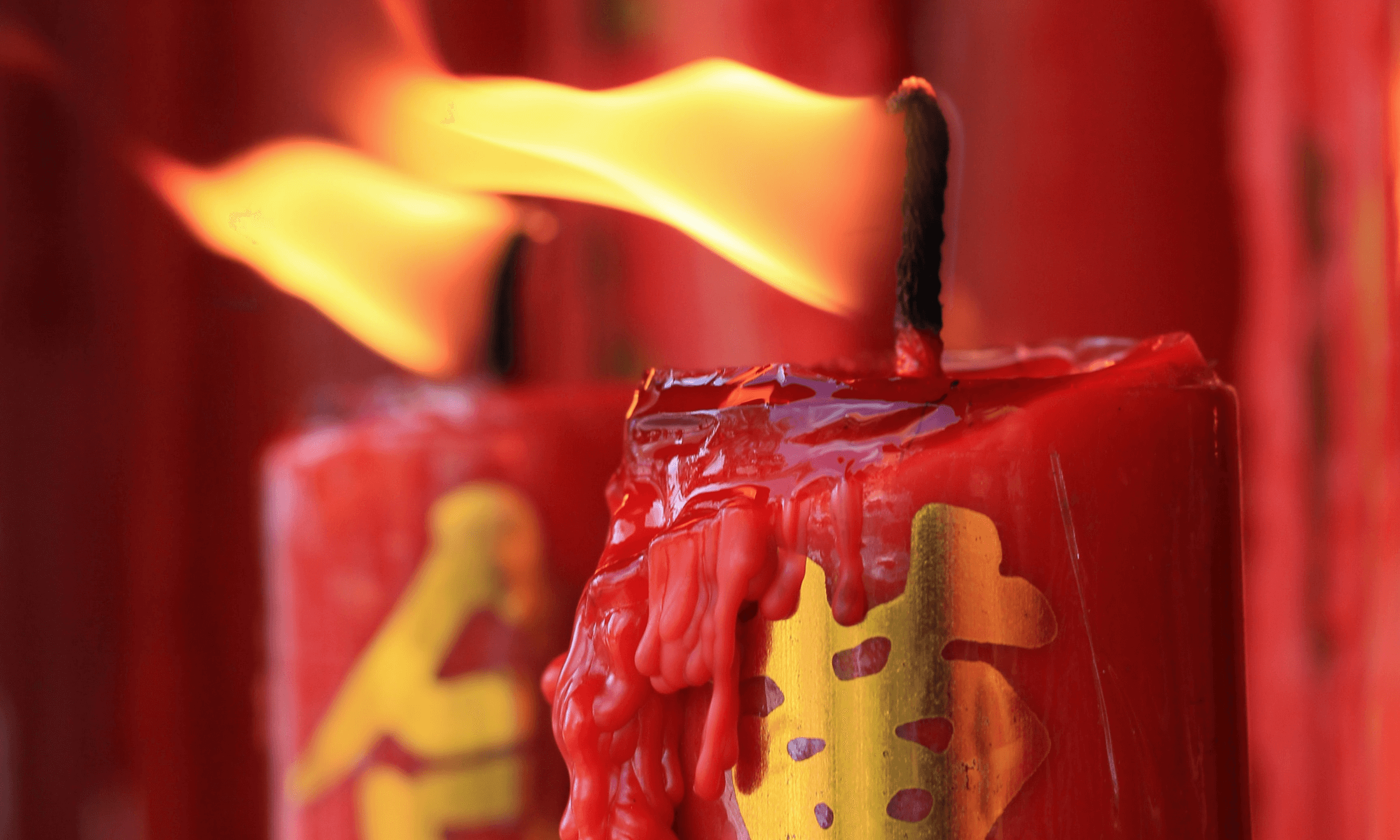

On July 4, my mother turned 67 years old, the same age as Mee Kuen was when she died. My mother too is Malaysian. It’s an understatement to say that the timing of it all, a week after Mee Kuen’s body had been discovered, hit close to home. I thought about my mum’s own journey from Malaysia to south London in the 1970s, some years earlier than Mee Kuen’s journey to Wembley. Growing up where I did, we didn’t have a large Malaysian community here save for a few of my mum’s friends from her time training as a nurse. My memories as a child are of her getting up early on a Saturday morning, usually at 8am, so that she could make a catch-up phone call timed to my grandmother’s afternoon in Sungai Petani, north-west Malaysia.

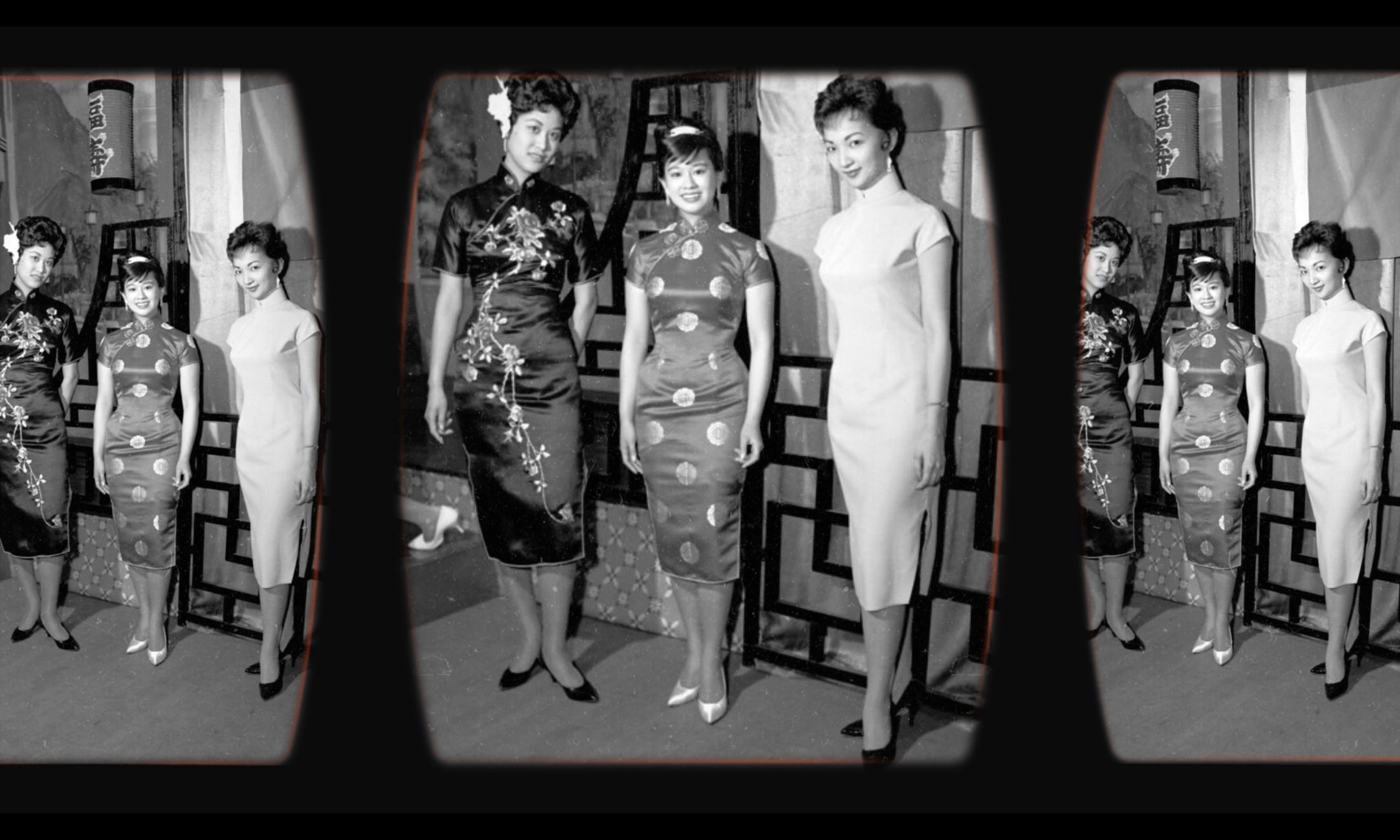

Despite not growing up within a community to collectively grieve with, I’m thankful for the community we have cultivated online over the last year during the pandemic. Through social media, younger generations of ESEA women have come together to resist and highlight injustices, in ways our mothers were not able to do as openly – not through any fault of their own, but because of the pressures to navigate and assimilate in a new, unfamiliar and at times, unfriendly country. Together, we have mourned the lives that have been lost when it feels like no one else has. We all owe it to women like Bennylyn, Mee Kuen and Louise, to honour their lives in the same way.

How reconnecting with my Vietnamese heritage led me to write a novel

This Lunar New Year, Asian communities deserve the right to grieve and fear

When will fashion brands stop sexualising the cheongsam?