How my quest for privacy in my Bangladeshi family has been a trade-off for affection

Ari Haque

09 Apr 2019

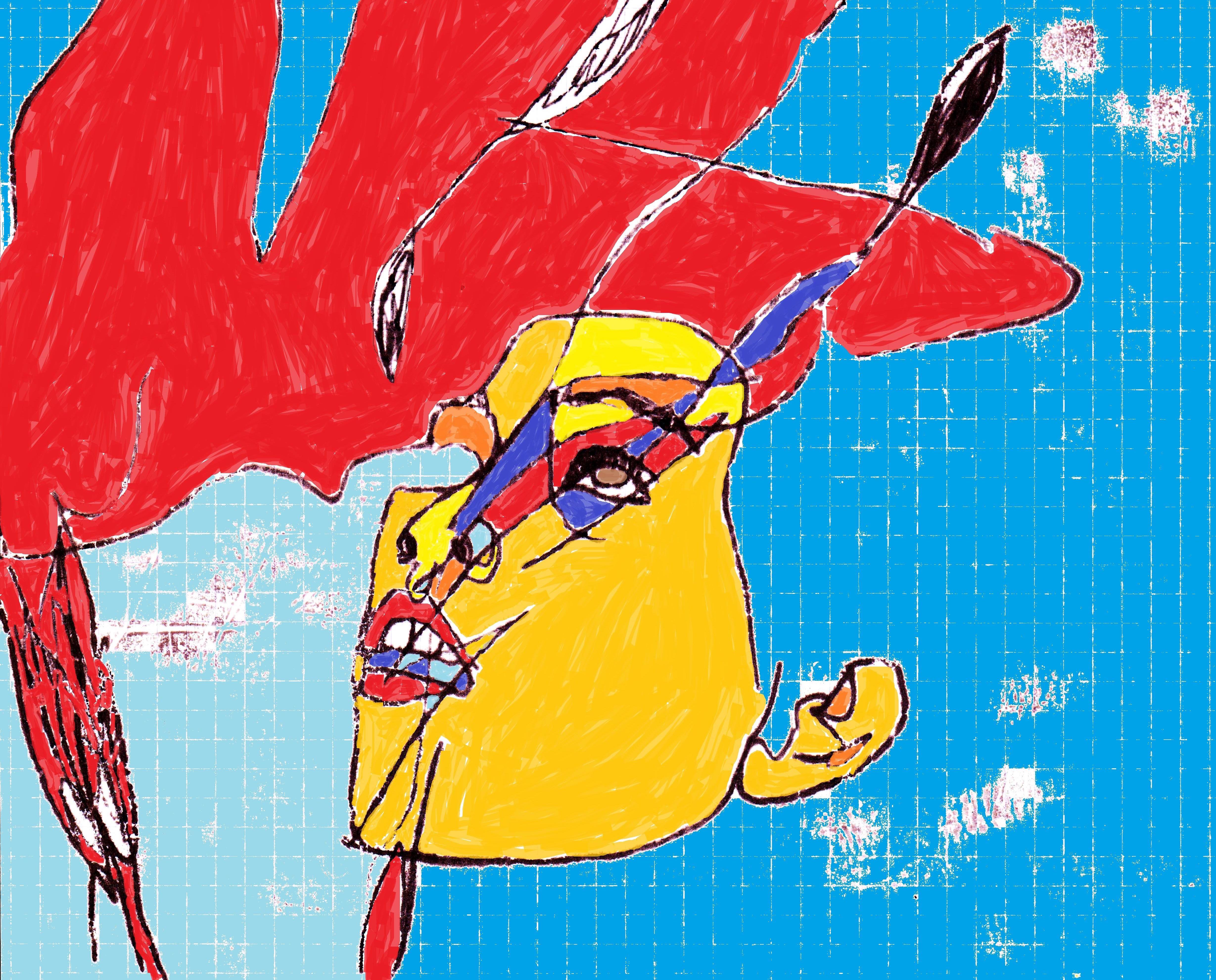

illustration by Alice Z Jones

South Asian homes are set up to be communal and familial. In Bangladesh, across different income and social demographics, parents and children sharing rooms is commonplace. This may have its roots in poverty and a lack of space and housing, but also has a basis in a different attitude to family space and the individual. Meanwhile, in England, my family lives in different cities, inhabiting not just different rooms but different social landscapes. However, when we return to Bangladesh, we still share a room. Who sleeps next to who changes and isn’t contentious, stripped of the overly proximate weirdness that a similar arrangement would have in the UK.

***

It is 1993. There is a bungalow with a tin roof. The outside is covered in a blue lattice. I don’t know the material; it’s almost like hardened string, lacing and interlocking like a vine. There is a cool stone passageway between the blue bungalow and the hut to its left, I remember it in browns and greys. It is unspectacular. There are four beds. Seven of us sleep there.

It is 1999, at least, maybe later. Opposite the courtyard behind the blue bungalow, where the tube well with fresh water stands, a creamy, a white building has sprung up. It is square, and inside there is a double bed and a reading desk. The attached bathroom has a commode. When we visit, sometimes eight of us sleep there (my brother has been born). Most of the time, there are four inhabitants.

It must now be 2005. Our visits are shorter, but the house has expanded. There are six beds (seven, if you include the one I never see). But we have littered: the house must now accommodate 14: parents, grandparents, brother, sister, great uncle and great-aunt, the two women who raised me when I was a toddler, a husband, and three children.

Sometimes I sleep in the room with two beds, the four of us confined to one room, whereas back in England we have one each, and don’t leave them much. Sometimes I sleep in the biggest double bed I’ve ever seen, the one in the blue bungalow, boro

“Having a room to yourself is the physical manifestation of the Western concept of privacy and individualism”

Having a room to yourself is the physical manifestation of the Western concept of privacy and individualism; my parents’ and I started locking horns about my independence when I acquired my own room. My parents were migrant doctors, and our family was often in transit, moving from place to place without settling roots until I was ten. We lived in rented houses, often unfurnished, sleeping on mattresses, sometimes two laid side by side in the same room. We clung onto it as a reminder of home, of Bangladesh – like Borrowers with a secret.

Obviously I knew this wasn’t “normal”. Being the bespectacled foreign “new girl” in every school makes you learn very quickly what is accepted, and the importance of never revealing any difference in yourself. I wanted to fit in; I wanted a room of my own. I wanted more than a box room for keeping my books, I wanted a proper bed with sheets that I had chosen and I wanted to sleep in my room, alone. But I was scared of the dark. Still, in year six, when my parents bought a house with three whole bedrooms and a garden (!), I slept in my own room, alone, soon to learn that there are much scarier things in the world than the dark.

The move coincided with the year I started growing body hair and my dad gently told me that it was nothing to be embarrassed about. He said I could use hair depilation cream if I wanted to. The first signs of puberty and the adolescent conflicts that would arise were further complicated by the cultural differences between how a Bengali girl is “supposed” to live and how I wanted to live. My parents thought it was about time I grew up and slept alone. But they weren’t so keen on me keeping the door closed. They still wanted full view; full access. I could have space, but there was no way it could be private.

I persisted. I wanted to make my space truly mine. I painted my bedroom walls firecracker red (as the shade was named on the Dulux paint chart) to demonstrate that I am mad and that my favourite colour is red. What’s the first rhyme you can think of for scarlet? I didn’t leave it to chance – I covered my ceiling in adverts from Vogue. Sexy pictures of objectified women which I would now find offensive, completely covering my ceiling. It was a real embarrassment for my parents when their Bengali friends came to visit. Their daughter: the Westernised tearaway, wearing jeans, piercing her ears several times, and covering her room with pictures of sluts, like her.

The bitter arguments about what I could and couldn’t do with “my” room reflects the culture clash experienced by immigrants and the shifting familial boundaries involved in a migration. Family norms and customs vary from place to place. In China, the state policy for looking after older people is that their children should do it. In the UK, one of the objections we cite about the broken care system is that it expects family carers to plug the gap, and we think this is unfair.

“I wanted to make my space truly mine. I painted my bedroom walls firecracker red to demonstrate that I am mad and that my favourite colour is red”

In Bangladesh, the home is a communal space. It is the family space, one that the patriarch owns and the matriarch manages. Children, even when grown up, will live there until they are married. Once they marry, the wife will move into her in-laws’ dominion, expected to live by a new set of laws and customs and give up her privacy to a group of near strangers.

I’ve often wondered: how does sex even happen with so little privacy, so many open doors? On one trip to Bangladesh, I remember my parents locking all three doors to the room we all slept in in the late afternoon. I wanted to get my book from inside the room, but found I couldn’t, even if I knocked. They surfaced a little later, and said that they had been sleeping.

The privacy inherent to the physical structure of our home in the UK means that I (thankfully) don’t have to think about my parents banging. I do wonder about my aunts, cousins, grandparents, and uncles living there all year round. I don’t know when sex happens; I’m curious but there’s no way I could ask. I assume the logistical difficulties around privacy and a squeamishness around sex that mandates discretion means that it happens less. Perhaps that reinforces the stereotype that sex is for procreation, and not pleasure.

My own grandparents, who are as liberal as you can get in Bangladesh (they had a scandalous “love marriage” in the 1950s) had clearly, if not openly, considered this. Before my parents married, my grandparents built the extension – the white cube with the attached commode. I realise now that this building was for my dad and his new wife, so they could have privacy.

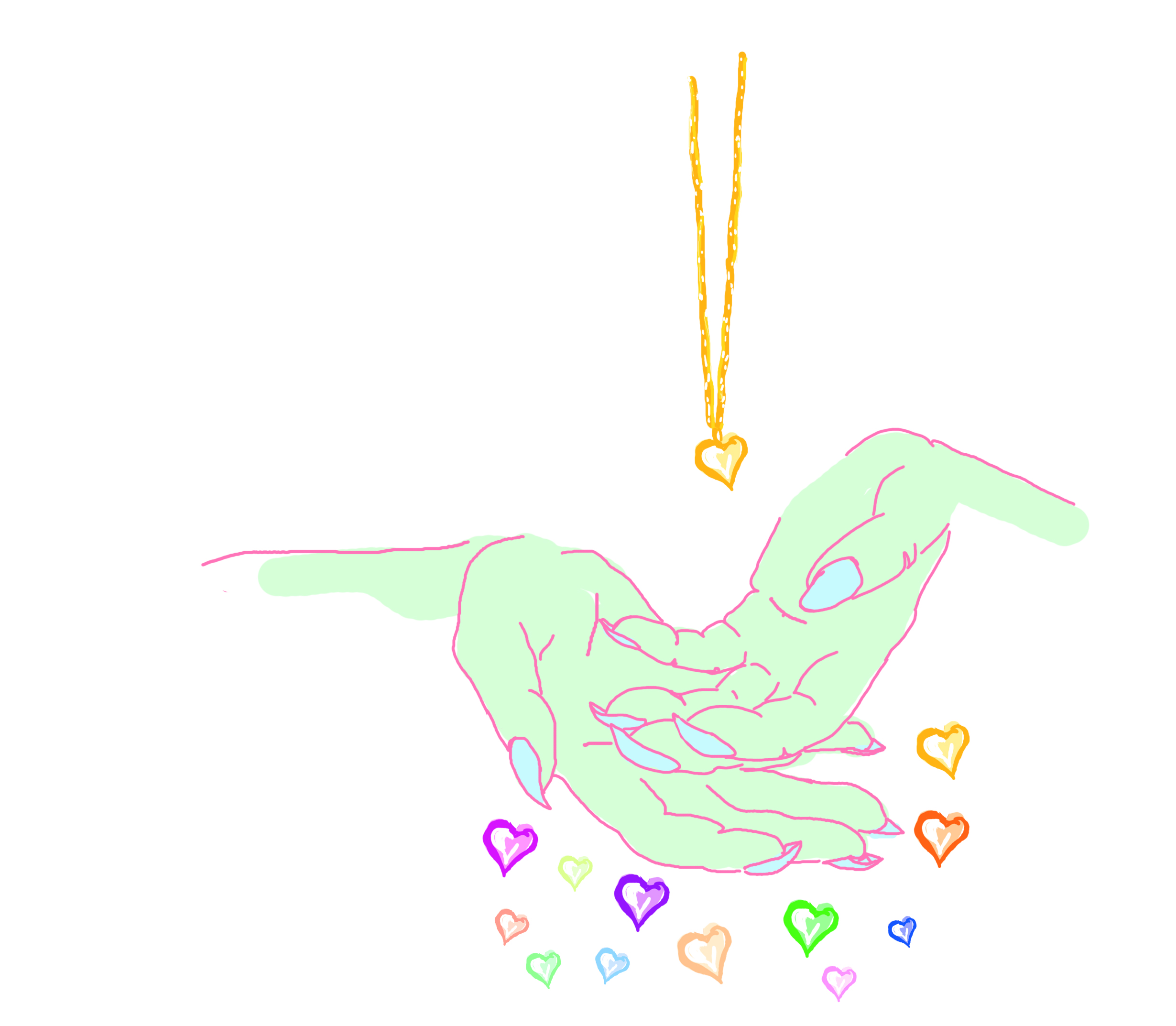

When I was born, I slept with my grandparents, presumably to give my parents some alone time. When I see my grandmother now (my grandfather passed away last year), she longs for me to share her bed although she never asks. It’s unsaid and unspoken but I’ve become too alienated from her for that to be comfortable. With my parents, in England, sometimes I can see that they want to give me a hug and my mum asks if I want her to sleep in my bed that night. I always say no, but sometimes, I wish I could say yes. The trade-off for privacy, after all, is affection.

From gal-dem’s second print issue, on the theme of home