‘People haven’t taken me seriously’: where the music and media industries have failed, whisper networks have provided solace and community

Jumi Akinfenwa explores how whisper networks have long operated under the radar – and the consequences once they’ve been thrown into the spotlight.

Jumi Akinfenwa

26 Jul 2022

Aude Nasr

This article is part of Open Secrets, a collaboration between gal-dem and VICE that explores abusive behaviour in the music industry – and how it has been left unchecked for too long. Read gal-dem’s Open Secrets articles here, and read VICE’s Open Secrets articles here.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of abuse and sexual assault.

In April 2022, a joint investigation by the BBC and the Guardian shared allegations from seven Black women accusing DJ Tim Westwood of sexual misconduct, namely “opportunistic and predatory sexual behaviour” over the course of three decades. (Westwood has “strenuously denied all the allegations” and a spokesperson has said they were completely false and denied in their entirety.). However, these accusations and behaviours were nothing new to people in the music and media industries, especially those from the Black community.

Despite Westwood’s strong denials and an initial statement by the BBC’s director general in April 2022 that the organisation had “found no evidence of complaints” being made to BBC managers about the DJ during his time working there, the BBC and the Guardian reported in July 2022 that the BBC had received six complaints about alleged bullying or sexual misconduct by Westwood, one of which was referred to the police. In July, the BBC reported that following their investigation, another woman came forward alleging she was a victim of statutory rape by Westwood, starting when she was 14 years old and he was in his thirties. Hushed murmurings of Westwood’s alleged predatory behaviour appear to have been swirling around for several years, in private conversations throughout the industry and beyond.

“Hushed murmurings of Westwood’s alleged predatory behaviour appear to have been swirling around for several years”

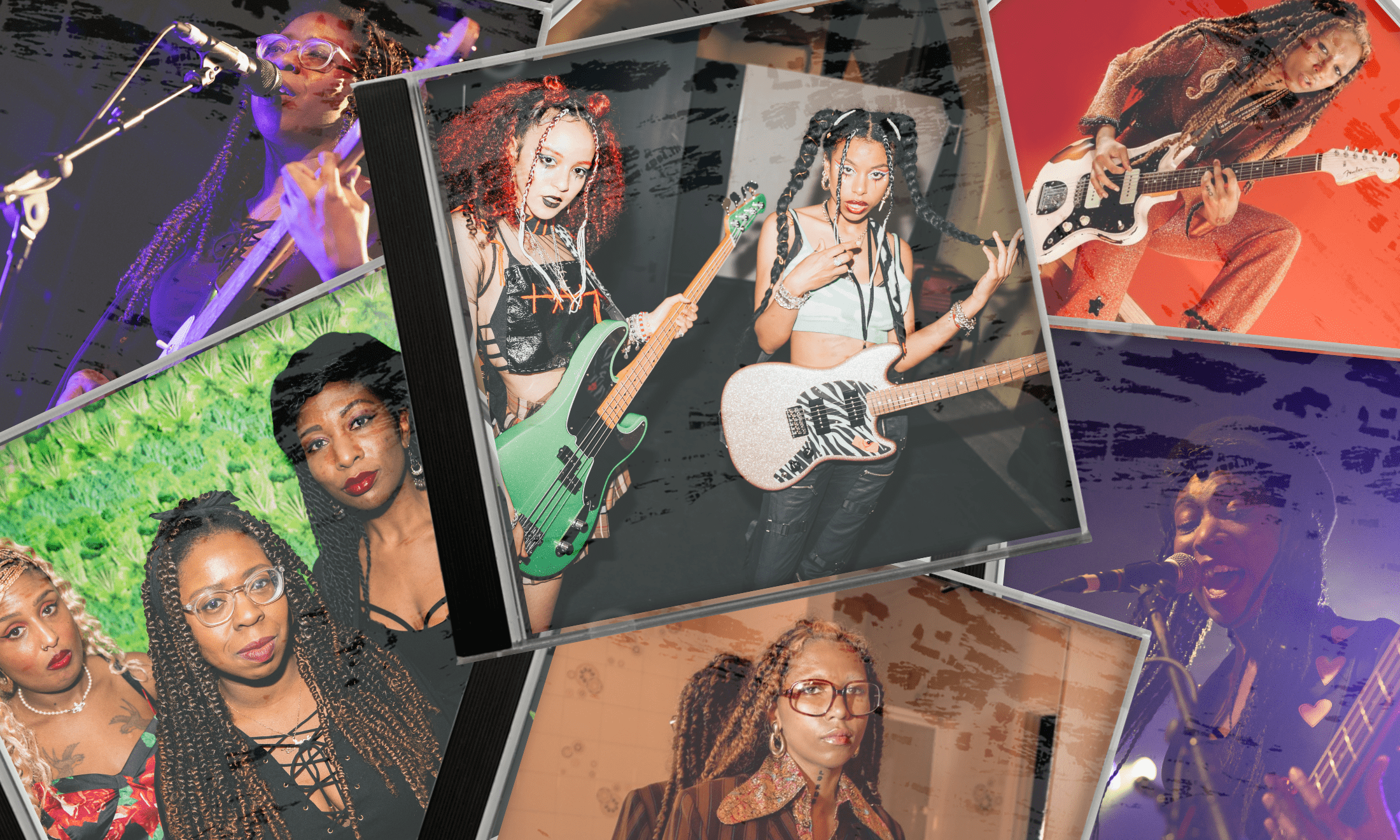

These types of conversations may be characterised as an informal whisper network, which have always existed in some form or another and have often been dismissed by some as a rumour mill. Whisper networks can be a casual, verbal peer-to-peer conversation (as appears to be the case with Westwood) or, in some cases, an informal collection of information usually shared between marginalised genders, typically about individuals who are known to abuse their power – be that by sexual violence, intimidation tactics or harassment. In recent years, such networks have gained more attention in public consciousness, triggered by the #MeToo Movement, with the publication of the Shitty Men in Media list, Harvey Weinstein Google doc and The Industry Ain’t Safe, an anonymous crowd-sourced Tumblr page for women in the music industry.

The primary objective of such networks is to keep marginalised people safe, as opposed to being a Burn Book-esque puritanical endeavour to ‘cancel’ all men, an outcome in itself that is often more fantasy than reality. Roberta Kaplan, attorney for Moira Donegan who created the ‘Shitty Men in Media’ list, stated that the intention of the list was “meant as a kind of a warning and as a protection mechanism”, as opposed to a witch-hunt against these men.

“The primary objective of whisper networks is to keep marginalised people safe”

Those who are involved with these lists are cognisant of the limitations of their own power and influence in their sector, compared to that of the people who feature on said lists – hence the underground nature of these networks. Abusers thrive not only due to the legal risks of survivors publicly speaking out, but also due to the culture of fear that persists within the creative industries. All too often, marginalised groups are demonised for speaking openly about any instances of abuse that they may have faced.

Rebecca* has worked in the music industry for several years who found solace in a whisper network after colleagues failed to support her. “From my perspective, as a woman of colour in the music industry, people haven’t taken me seriously when I’ve talked about my experiences with assault in the past,” she says. “I’ve been forced to sit in meetings and pressured to work with individuals that have sexually assaulted me. When expressing that I felt an artist was behaving in a sexually aggressive manner towards me, I was told that I was ‘imagining it’ or ‘should be lucky for the attention’.”

“As a woman of colour in the music industry, people haven’t taken me seriously when I’ve talked about my experiences with assault in the past”

Rebecca

For some, anonymised collectives are currently the only tangible way forward when it comes to safeguarding marginalised people in creative industries. “Most companies do not have a strong infrastructure in place for how to deal with sexual assault and oftentimes the survivor receives blame or is re-traumatised by the process,” says Jess Kangalee of Good Energy PR, a music promotions company prioritising queer artists of colour. “When you have been devalued, stigmatised and not taken seriously reporting ‘minor’ incidents, why would you trust that same institution to handle a more serious complaint when [they] have in essence been responsible for the lack of education and conversation around how to treat people within a working environment?”

This sentiment isn’t unique to music, but stretches across the wider creative industries into spaces which others may deem to be inherently safer. Sam*, a London-based artist who works with a range of creatives and collectives from a mix of socio-economic backgrounds and gender identities, says institutional issues persist even in more progressive spaces.

“Existing leaders take little responsibility for issues embedded in their working environment,” they say. “This means that problems are repeated, and it feels like you’re stuck in a loop, whilst iterations of a supposed progressive workspace wash over you, with little impact to your well-being. So naturally whisper networks could operate as a way of feeling connected to others.”

“The intention of whisper networks is often to protect and provide community as opposed to being a robust remedy for systemic abuse”

The intention of whisper networks is often to protect and provide community as opposed to being a robust remedy for systemic abuse. But leaks of information about alleged abusers to the public are not an uncommon outcome. On the surface, public awareness of those who abuse their power may be seen as a means to prevent them from causing further harm; however in some instances, it has resulted in legal ramifications. The ‘Shitty Men in Media’ list was leaked in 2017, leading to a defamation lawsuit against Donegan which may soon go to trial.

Whilst alleged victims’ names were undisclosed in this instance, it’s not always the case that identities are adequately protected, given that public exposure is rarely the intended outcome. The public knowledge of identities can lead to anxieties about job security, online threats, doxxing and even suggestions that the accounts are completely false or that the alleged perpetrators’ actions were merely misinterpreted.

“For many Black women in particular, the mainstream indifference towards alleged abuse inflicted on our community is enough to call for an end to the whispering and for more shouting to take place”

It took more than 30 years for the allegations against Tim Westwood to be reported by two major media outlets. For many Black women in particular, the mainstream indifference towards alleged abuse inflicted on our community is enough to call for an end to the whispering and for more shouting to take place. More often than not, the reputations of self-serving individuals take precedence over providing support for those attempting to vocalise their experiences of alleged abuse who are likely in more precarious positions within the industry. If we are to see systemic change and accountability, structures need to be put in place to protect those brave enough to come forward –and these cannot solely be upheld by fellow marginalised people.

For Kangalee, the Tim Westwood allegations may serve as a tipping point for the music industry, a sector that has seemingly still dodged the brunt of widely publicised cases of misconduct. “I am hoping this finally ignites a much needed ‘#MeToo moment’ in UK music as we haven’t had one,” she says. “There are so many offenders that we all talk about that have been allowed to carry on and haven’t been called out or held accountable for their actions – and that needs to happen.”

* Name has been changed to protect identity

For a full list of resources related to this article and the Open Secrets Series, visit our Open Secrets Resources page here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.