Here are some of the organisations advocating for marginalised genders’ safety in music spaces

From Cactus City to Pxssy Palace, here’s a few groups looking to ignite change in how studios, nightlife and the music industry as a whole protect the most marginalised.

Rahel Aklilu

28 Jul 2022

Aude Nasr

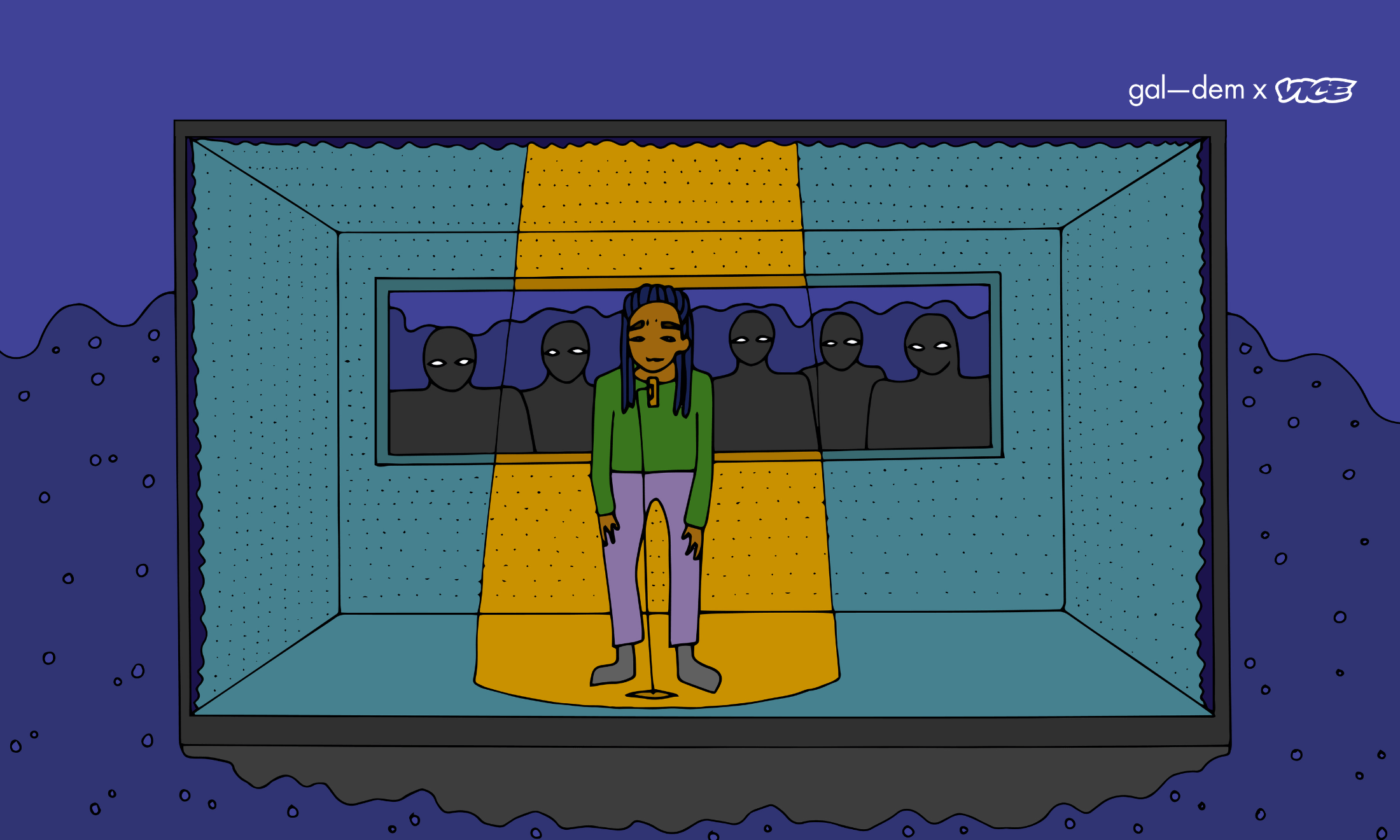

This article is part of Open Secrets, a collaboration between gal-dem and VICE that explores abusive behaviour in the music industry – and how it has been left unchecked for too long. Read gal-dem’s Open Secrets articles here, and read VICE’s Open Secrets articles here.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of abuse.

The music industry and nightlife are inextricably linked. Where one has fostered a breeding ground for abusive behaviour during the day, the other has served as a place to facilitate such behaviour at night. As much as the office, working in music means working in basements, nightclubs, festivals and social events. And with ‘networking’ being a key factor in meeting the right people at the right time across the music industry, there is something of an unspoken rule around attending events as a way of building a name for yourself.

Whether it’s in the boardroom or backstage, the music industry has never been a safe space. Over 40% of women under 40 in the UK have been assaulted at a live music event – and that is only those who report it. Many don’t – not only out of shame, but because there is no structure of serious accountability and support that helps them. It’s for this reason that spaces specifically cultivated by communities offer solace and safety.

“Over 40% of women under 40 in the UK have been assaulted at a live music event – and that is only those who report it”

As the world reopens following lockdowns, many of the fears marginalised people had around live events and the music industry are back, with good reason. Not only are nightclubs a space for self-expression, they are also known for forging specific subcultural and political identities. They provide space for marginalised communities to gather and socialise in a space that prioritises safety. It’s for this very reason that some club nights have evolved into sanctuaries and communities in their own right, like South London’s BBZ and fan-favourite Pxssy Palace.

Although there has been much talk of making the music industry a ‘safer space’ what does that actually mean beyond seemingly aimless reports and empty promises? In 2021, UN Women launched a project in conjunction with festival Strawberries and Creem entitled ‘Safe Spaces Now’, calling for the music and live event sectors to commit to tackling harassment and to create safe spaces for marginalised genders. The initiative has been backed by radio presenters, festival organisers and artists alike. ‘Safe Spaces Now’ has proposed over 150 solutions for fostering safety from harassment at music events, nightclubs and festivals.

“Some club nights have evolved into sanctuaries and communities in their own right”

However optimistic this report may seem in enacting real change with forecasts for the next 10, 20 or even 30 years, there are organisations on the ground, made up of marginalised genders to protect marginalised genders. Rather than relegating safety to a secondary impact, they have centred their work on it, working alongside their communities to ignite change from the ground up.

Cactus City

Founded by music manager Vanessa Threadgold in 2017, Cactus City started out as a recording studio exclusively run as a safe space for women and minority genders. This was following a series of incidents that left Vanessa’s management roster (all women) uncomfortable in studios. These ranged from artists being invited to studios under the pretence of work, but actually transpiring to be an opportunity for harassment; music being held back or even deleted if women refused comply with inappropriate requests; as well as artists being blacklisted for requesting to bring chaperones.

Salli Flaherty, a former artist with Cactus City who was later enlisted by Vanessa to help grow it from a studio to a fully fledged organisation, explains: “the biggest issue facing the safety of women and marginalised genders is the culture of silence that permeates every corner, reinforced not only by legally binding NDAs but also by a fear of blacklisting, in a profession where most are freelancers and depend upon networks and relationships to help generate work and therefore income”.

In response to the outpour of support since officially launching in 2020, Cactus City have also released a ‘Charter of Good Practice’. “Our charter provides music studios – a place where many people first find themselves in the first stages of their career – a straightforward way to supplement any policies they may already have,” Salli explains. She points to the small mannerisms such as greeting everybody in the room when entering to arranging safe and accessible sessions – things that set boundaries in an often unregulated space. By setting these standards, the studio becomes a safer space for creative freedom for all to enjoy without fear of harassment.

Good Night Out

Founded In 2014 as an offshoot of anti-street harassment campaign ‘Hollaback London’, Good Night Out (GNO) exclusively tackles safety in music, nightlife and culture spaces through delivering accredited training to all levels of venues and promoters. They train staff working at everywhere from festivals to student unions in how to respond to and prevent sexual harassment in night time spaces. Having helped fabric London draft it’s first ever anti-sexual harassment policy, GNO has since gone on to work with several London councils on safety charters, including Hackney council on it’s ReframeTheNight campaign, aimed at challenging myths and stereotypes around sexual harassment through GNO’s training as well as other means.

June Bellebono, a community organiser, event producer and writer is also one of the trainers at GNO, points to the broad range of collaborators they’ve been able to work with whilst delivering training all over the country. “Another really good move we’re seeing is councils funding venues to take part in the training, so that we can accredit a number of spaces in physical proximity.” This in turn could create safer areas for marginalised people to go out, in the knowledge that spaces in a similar area would hold the same stringent policy to protect safety.

The training itself includes a run-through of the legal framework addressing sexual harassment as well as talk through ways venues can tackle the issue, how they’d like their space or nights to run, possible scenarios and how to deal with them. Having worked with over 185 spaces around the country, a number that’s bound to increase as the nightlife economy slowly but surely bounces back, the work GNO carries out introduces accountability for safety at an organisational as well as moral level, allowing venues and promoters alike the chance to enact a real, lasting commitment to prioritising safety in spaces.

I’ve Been Spiked

When Mair Howells was spiked in February 2020, her experience was one of unhelpful bar managers, a lack of resources for support and little recollection of how she was spiked. And so, she started ‘I’ve Been Spiked’ an Instagram page sharing infographics on where to find support after being spiked, as well tips on looking after those who have been spiked and ways to spot it.

“The page honestly started out of frustration and a search for answers,” she explains, “I spent a lot of time after my experience looking for resources or an explanation as to what had happened – there was very little online. I found sharing my story very cathartic but it also made me realise how many other people had also had a similar experience.” Indeed, as university students returned to physical campuses after a year and a half online, there was a rise in reported spiking incidents between September and November 2021. The National Police Chiefs Council said there have been 198 confirmed reports of drink spiking in September and October across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, plus 24 reports of some form of injection.

However, as Mair notes, survivors are unlikely to report to the police, not only out of a misguided fear and shame but also because there is simply no system of accountability to address spiking without clear proof, from testing to recording the incident to reporting the crime. “There are massive grey areas in testing if you believe your drink has been spiked, and then when reporting the crime to the police, which means a lot of cases fly under the radar,” she says, “Often people are kicked out of clubs in vulnerable states after they appear ‘too drunk’ when really they should be met with support and help”.

‘I’ve Been Spiked’ provides a space for survivors to share their stories, resources and ideas for raising awareness of what spiking may look like and how everybody – from bystanders to bartenders – has a role to play in protecting each other.

Solidarity Not Silence

Solidarity Not Silence was born out of a collective effort to raise money for legal costs for a group of survivors silenced by threats of legal action against them following accusations of abuse against their common accuser, who sued them for defamation. Composed of women in and around music as well as former partners of the accused, the group has, as of August 2021, settled their case after four years of litigation. The protracted legal battle in their bid for justice serves as a reminder of the protection afforded to many abusers through power and money to continue their careers as well as silence their accusers. With their case closed, they have maintained a lower profile, though their website says they are focusing their efforts on campaigning and enacting solidarity for others in similar situations.

Pxssy Palace

Pxssy Palace has set the blueprint for inclusive clubbing that many have since followed. A self-described ‘SLAGGY INTENTIONAL CLUB NITE THAT CELEBRATES & CENTRES QUEER WOMEN, TRANS, NON BINARY & INTERSEX BIPOC’, it has been a staple on the London scene since 2015, founded by Glaswegians Nadine Noor Ahmad and Skye Barr. The night has since evolved into much more, forming a community that hosts everything from podcasts and festivals to fundraisers.

They have moved away from the language of “safe space”, aware it is irresponsible to claim they can provide absolute safety: instead, they work intentionally to try and make things as comfortable for their community as is possible. At nights, they’ve developed a sanctuary for clubbers to breathe and relax amidst the chaos of the dancefloor, along with a number of other mechanisms to promote and protect the safety of attendees. These range from it’s zero-tolerance to harassment of any kind, reinforced and reiterated before every event, to the free taxi donation fund at the door that pays for taxis home for BIPOC trans, gender non-conforming, and/or disabled peoples.

Once you’re actually in the party, ‘Badge bitches’ (who are volunteers) make themselves known as a friendly face on the dancefloor to open up to or report any issues. Pxssy Palace has found a place for itself at the intersection of nightlife and political activism, using one to support the other by fundraising and donating surplus donations from the taxi fund to QTIBPOC fundraisers. Where other club nights may fail to hit the mark, they have centred safety in a way that promotes freedom and acceptance for all needs and concerns.

For a full list of resources related to this article and the Open Secrets Series, visit our Open Secrets Resources page here.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.